In Lieu of the Bountiful Triple Dip

3rd Quarter, 2024

The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office ramped up its estimate for this year’s US budget deficit by 27% to almost $2 trillion, sounding a fresh alarm about an unprecedented trajectory for federal borrowing.

The CBO sees the deficit reaching $1.92 trillion in 2024, up from $1.69 trillion in 2023, according to updated projections released in Washington Tuesday. The new estimate is more than $400 billion larger than what the CBO anticipated in February…

~ Bloomberg, June 18, 2024

Reminds me of that fella back home who fell off a ten-story building … as he was falling, people on each floor heard him say: “So far, so good.”

~ Steve McQueen, in The Magnificent Seven

So far…so good?

* * *

When inflation begins to upend financial markets, as it has over the past few years, it represents a tremendous disruption. A transition from an era of falling inflation rates to one of higher inflation rates set off a chaotic adjustment of prices, valuations, and sentiment that cascades though financial markets and the economy. The full progression of that disruptive pivot takes time to run its course.

We have reviewed how the Great Inflation began in various articles over the past six years, and we have devoted so many pages to this topic because the last time a disruptive inflationary transition took place, Lyndon Johnson was President and McChesney Martin was head of the Federal Reserve. It was 1965, a long time ago. Many of the hard lessons investors learned during that era have largely been forgotten.

* * *

By all appearances in early 1965, inflation was nowhere in sight. Over the previous decade, inflation had averaged just 1.8% per year, and interest rates were low and stable. It was an established regime of low and stable inflation which was, on the surface, not unlike the decade prior to 2021.

Yet long before then, legendary investor Benjamin Graham had begun to wonder why the stock market appeared so overvalued by nearly every metric he tracked, but continued to relentlessly advance anyway. Early on he suspected investors were anticipating something new, or that their preferences had changed in some fundamental way. Eventually he concluded the reasons had to do with the unique aspects of the post-war experience – specifically, with inflation.

Back in 1955, Graham had testified before the United States Senate about the booming stock market. Unlike the turbulent downturn following the end of World War I, the economy and markets had soared after World War II. In the year after the end of hostilities in 1945, the Dow Jones Industrial Average quickly rose above 200, which was the first time it had reached that level since the earliest days of the Great Depression. By 1951, it had risen another 25% to above 250. And by the time Graham sat in front of the Senate Committee on Banking and Currency in March 1955, the DJIA was rapidly closing in on 500 after a near vertical rally over the previous two years.

The meteoric rise after WWII was in sharp contrast to the collapse of the market and the onset of deflation following WWI. In looking for the reasons behind the surge, Graham’s opening remarks to committee Chair J.W. Fulbright suggested he had already come to suspect that investors themselves were the main reason the markets were acting differently than they had in recent years.

A few moments into his testimony, he offered the following assessment to that effect:

With respect to the present level of stock prices, my studies lead to the impression that leading industrial stocks are not basically overvalued, but they are definitely not cheap; and they are in danger of going over into an unduly high level…

With respect to the cause of the rise in the market since September 1953, my statement indicates I would emphasize very much the change in investment and speculative sentiment, more than any change in basic economic factors…

Quantitatively, the market seems about right, but qualitatively I consider it to be on the high side and getting into a dangerous situation.

In the years after 1955, despite Graham’s assessment that the market was already “getting into a dangerous situation,” the meteoric rise continued. After consolidating near 500 in 1956, 1957, and 1958, the Dow Industrials began to rally again in 1959, and never looked back.

By 1963, with the market having quickly recovered from another brief and shallow correction earlier in the year, Graham again ventured to comment on the markets in a speech in San Francisco we reviewed in How an Inflationary End to the Bountiful Triple Dip Swindled Equity Investors. By this time, with the Dow Industrial Average trading near 800, his thinking had evolved.

Although the market’s price and valuation were higher in 1963 than in 1955, Graham was convinced investor sentiment had gone through a sea change with respect to equity market risk. Investors were now willing to pay much higher valuation multiples for common stocks than they had in the past – that much was clear. Graham reasoned this was due, in large part, to the fact that continuous inflation, without subsequent corrective episodes of deflation, had seemingly become a durable feature of the post-war economy.

* * *

As brilliant as Benjamin Graham was, he almost certainly could not have imagined how much continuous inflation lay directly ahead. Little did he know as he was speaking in the ballroom of the St. Francis Hotel in San Francisco in November 1963, events already in motion would shortly thereafter lead to the end of the second Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates, a devaluation of the equity market that would rival the value lost during the Great Depression, and a hockey-stick pivot in consumer prices that continues to this day.

The earliest hints of those looming events could be seen in the data by 1965.

The march toward the hockey-stick pivot in prices began in 1964 with a series of tax cuts, which had been proposed under the late President Kennedy in 1963, but which were passed under Lyndon Johnson. It continued with the expansion of spending related to the war in Vietnam and the new Great Society programs. Unlike the New Deal programs of Johnson’s political idol, Franklin Roosevelt, which sought to back-fill the economic void of the deflationary Great Depression, the tax cuts and the expansion of federal spending in the mid-1960s came at a time of strong economic growth and low unemployment. The result of this flood of stimulus on an already strong economy was the first significant inflationary pressures in more than a decade.

The markets took immediate notice of these new inflationary pressures, as did central banks.

The Federal Reserve began its response to rising inflationary pressures in late 1965, and immediately thereafter, Fed Chair McChesney Martin felt political pressure bear down on him from President Johnson in the form of a fiery confrontation at his Texas hill country ranch. Foreign central banks, outside of the orbit of Johnson’s infamous persuasiveness, began to convert their devaluing dollar reserves to gold to preserve value.

As a result of the expanding supply of dollars and the departure of gold, despite beginning the 1960s with enough gold to cover 85% of foreign currency reserves, the U.S. ended the 1960s with only enough to cover one quarter of those liabilities:

The nature of trends like those shown in the table above are such that they tend to slowly build over time until, one day, often quite suddenly, it causes something to break. Astute observers notice the subtle signs that things are increasingly amiss in the lead up to the break, and as a result, they are often better prepared when it happens. Yet even for the most astute observers like Graham, it is a challenging task to navigate markets during such turbulent times.

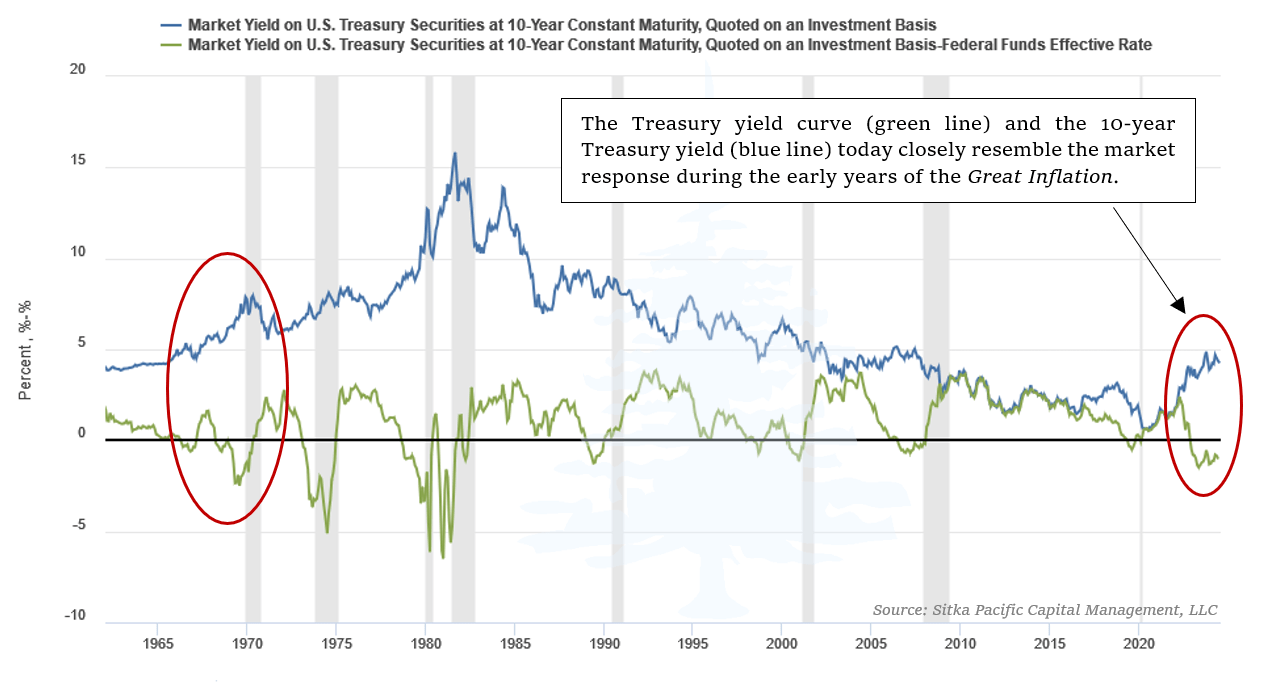

The monetary trends which led to the final end of dollar convertibility in 1971, and the Great Inflation that followed, began to subtly impact markets years beforehand. Although official inflation numbers remained benign in early 1965, as the year progressed the bond market began to take notice of the rapidly growing supply of dollars. The yield of the 10-year Treasury note began to rise late in the year, and by February 1966 it had popped up to 4.8%. This was not only a post-war high yield – it was the highest 10-year Treasury yield seen since 1921.

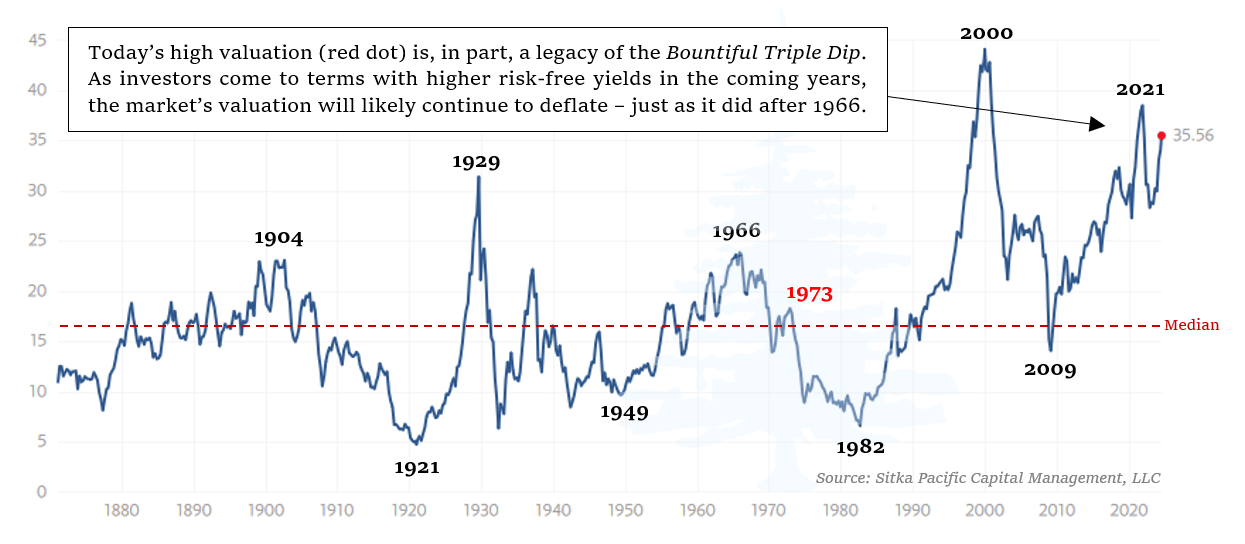

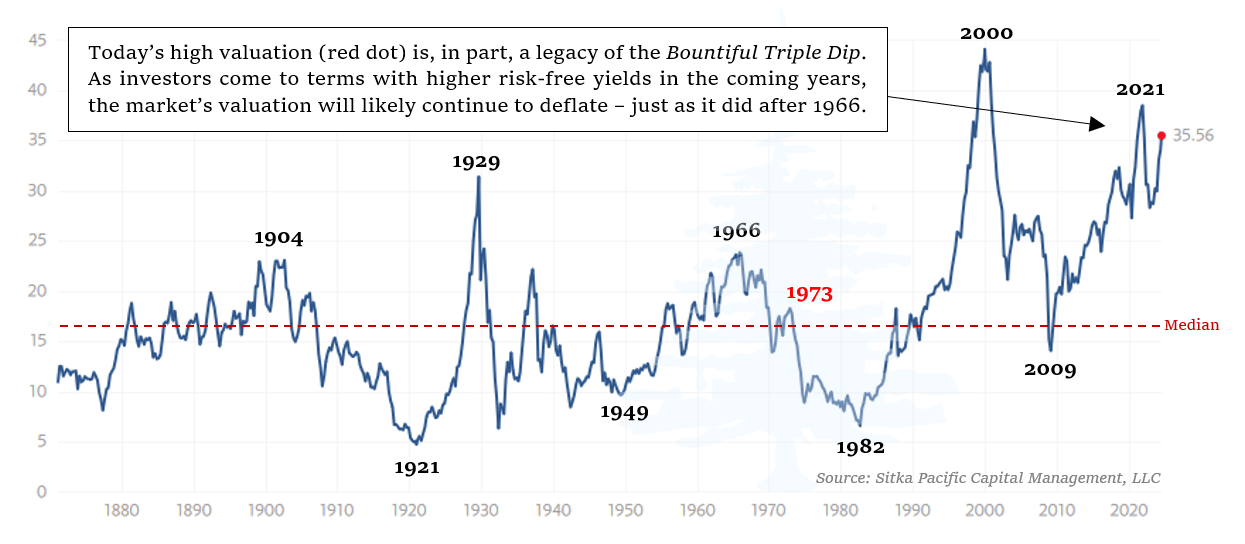

The same month the 10-year Treasury yield reached a new 45-year high, the stock market also took notice of the changing landscape. The high watermark of the broad equity market’s valuation that was established in early 1966 would remain unbroken until the mid-1990s, and the long, slow descent from that valuation peak over the following seventeen years would prove to be an extraordinarily difficult headwind for stock market investors.

At first, the equity market’s valuation contraction proceeded slowly, and investors began responding to the new headwind to their portfolios by starting to overweight stocks, especially those which appeared relatively immune from the impact of bond yields.

Yet as federal deficits and inflationary pressure steadily increased, bond yields rose uncomfortably high. By 1969, the yield on the 10-year Treasury had risen above 7%, and the headwinds facing the equity market strengthened. This left stock market investors with fewer and fewer attractive choices, and in their growing desperation, they began crowding into the shrinking list of stocks which were still performing well. Sensing the growing risk that year, Graham’s protégée, Warren Buffett, decided to close his investment partnerships, citing the unfavorable market environment.

What happened next is directly relevant to our circumstances today.

As yields continued to rise into 1970, bond prices fell further. By this time, bonds had increasingly become a source of aggravation and negative real returns to diversified investors – just as they have over the past four years. From 1965 to 1970, the total nominal return of bonds was negative, and the inflation-adjusted value of a diversified bond portfolio had fallen by more than 20%.

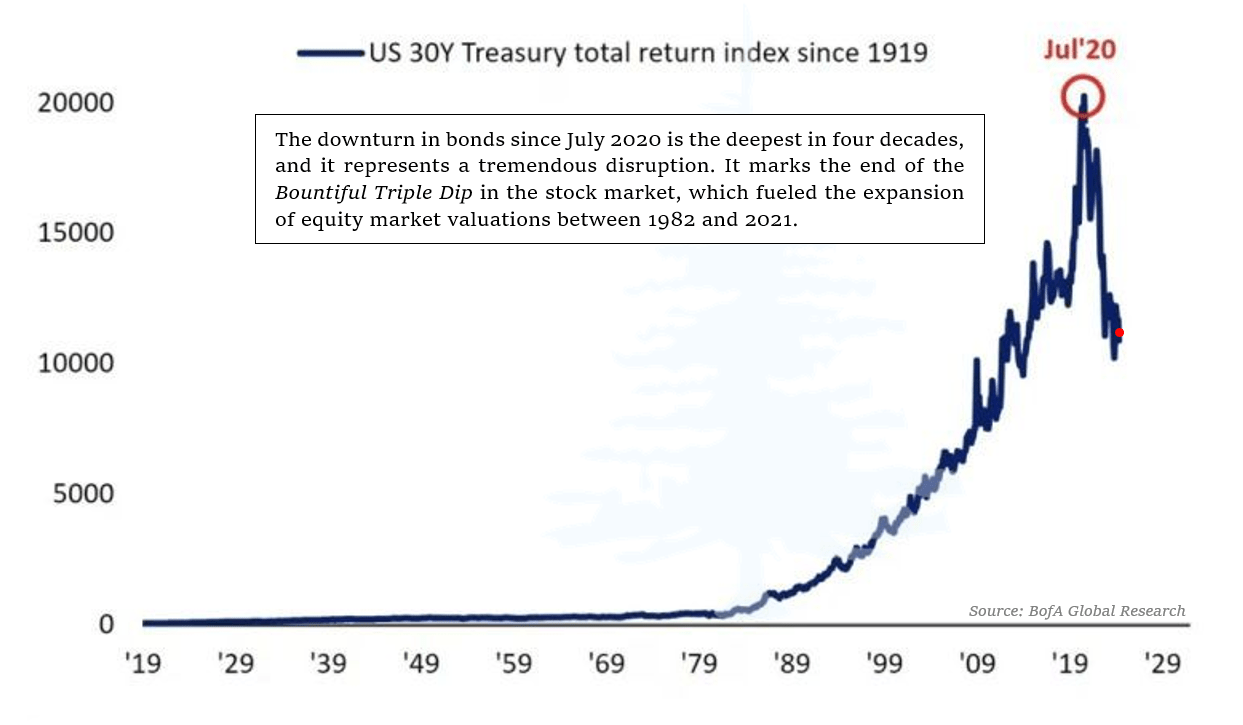

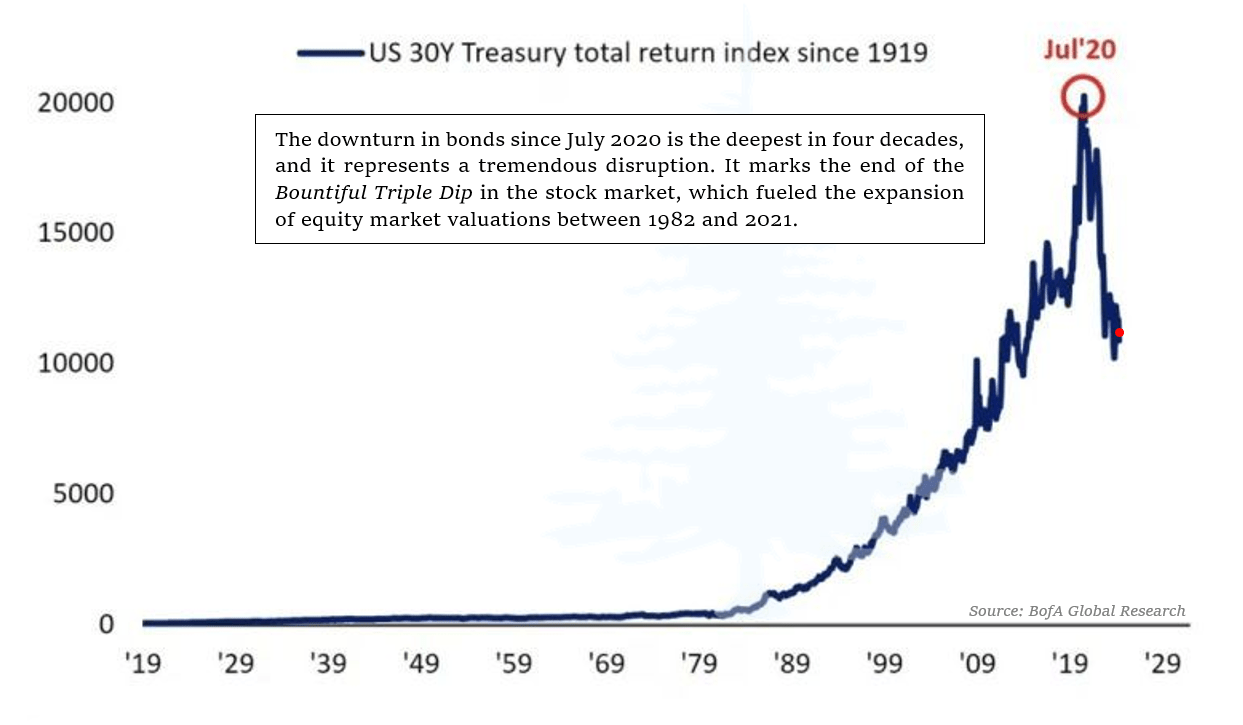

Bond investors over the past four years have had a similar, if not more severe, experience. Since 2020, when yields hit their lowest levels in history during the height of the pandemic, an investment in the longest-term Treasury bonds has lost nearly half its value. With the 21% rise in consumer prices so far this decade, the past four years now rank as the steepest loss of real, inflation-adjusted value in the history of the Treasury bond market.

During the first three years of the 1970s, bonds fell further out of favor as inflation became more entrenched. Bonds began to be viewed as “certificates of confiscation.” In lieu of bonds, investors crowded further into stocks, especially those stocks which seemed to offer protection from inflation.

By 1973, the result of this crowding was the most concentrated mania since 1929.

Stocks deemed one-decision investments at the time were those whose businesses were either resistant to inflation, or benefited from it. The reasoning at the time said that it did not matter how much an investor paid to own a part of those businesses, as with inflation rates continuously rising, there would certainly never be a time to sell them. Hence, the only decision investors had to make, the one decision to make, was to buy – at any price. “The Nifty Fifty stocks are the ones that will grow come what may, and are most insulated from the interest-rate and inflationary pressures,” reflected the sentiment at the time.

Investment managers justified owning stocks at 50-times earnings or more by pointing to their continued earnings growth despite rising inflation and high bond yields. John Bennett, of Putnum Investments, reflected this thinking. He was asked at the time how he justified owning Johnson & Johnson at 57-times earnings. Apparently with a straight face, and after a puff from his pipe, he replied: “If you look at their earnings out seven years from now, the stock’s not really that expensive.”

The equity market’s capitalization became overly concentrated in a few dozen stocks as the mania grew, but the strength of the few could not mask the growing weakness in the many. Despite the high valuations of the Nifty Fifty, the rest of the equity market was devaluing. While favored stocks like J&J rose to trade at 57-times earnings, unfavored stocks like U.S. Steel sank to 5-times earnings. “Growth” during this time outperformed “value” by a record amount, but the list of stocks deemed growth stocks was rapidly shrinking, while the list of value stocks was rapidly expanding.

At the peak of the mania, the S&P 500 index’s Cyclically-Adjusted Price-to-Earnings ratio had deflated from 24 to 18, and investors had become heavily concentrated in a few dozen winning stocks trading at extreme valuations. This gave an impressive illusion of strength to major equity market indexes. However, it was a fragile set of circumstances which then suddenly broke down after January 1973.

The Nifty-Fifty was a mania which sprouted and grew in lieu of the Bountiful Triple Dip.

Eight years after closing his investment partnerships, Warren Buffett coined the term in a Forbes column to describe the virtuous cycle that boosts equity market returns when inflation rates and bond yields are low, and the subsequent vicious cycle that begins when inflation rates and bond yields begin to rise. Investors, who after 1966 no longer enjoyed the elevated passive returns which come from expanding equity market valuations, turned to increasingly desperate speculation in seeking returns in the early 1970s, until the fragile, concentrated façade broke in 1973.

* * *

What began in the 1950s and early 1960s as an initial response to continuous inflation by investors, morphed into an irrational exuberance by the early 1970s. A half century later, we find ourselves in a market environment similar to those exuberant years between 1966 and 1973.

As bond yields have risen over the past four years, and inflation rates have become entrenched above the sub-2% readings of the 2010s, the broader equity market’s valuation has modestly deflated from its peak in 2021. However, the valuation deflation which has impacted the vast majority of stocks has been masked by a mania in a small handful of technology stocks – the Magnificent Seven. These stocks have become the close kin of the one-decision stocks of the Nifty Fifty era, as investors have again concluded no valuation is too high for these select few that appear immune from the impact of rising inflation and yields.

The excerpt below from a Bloomberg article in June of this year could have easily been written in 1973, if Johnson & Johnson, Baxter, and other high-flying stocks of the Nifty Fifty era were substituted for Apple and Nvidia:

Take out the few big tech companies that keep pushing the S&P 500 Index to all-time highs and it looks like the engine is running on fumes.

While the index is marching from one record to the next, fewer and fewer stocks are participating in this year’s rally. Nearly a third of its constituents have hit a one-month low in the past month, data compiled by Bloomberg through the end of last week show. That far outnumbers those that are pushing it higher. In fact, just 3.2% hit a one-month high, including Apple Inc. and high-flying Nvidia Corp…

“Sellers are entering the market, and bulls are dancing on the edge of a knife,” said Andrew Thrasher, a technical analyst and portfolio manager at Financial Enhancement Group. “Everything is now dependent on pretty much just Nvidia and Apple. It won’t take a whole lot to take this market down.”

As of the end of the 2nd quarter, the Magnificent Seven stocks represented an astonishing 31% of the S&P 500 index’s market capitalization. By some measures, the concentration of the major equity indexes has not been this narrow in more than half a century. At its highest price in June, the highest-flying of the Magnificent Seven traded at a stratospheric price-to-earnings ratio of 82, which means that a passive investor in the S&P 500 index is now holding an investment more concentrated in extremely overvalued stocks than at any other time since the Nifty Fifty era.

In the long run, high valuations beget low long-term returns – this is well established by centuries of market data. However, it is also true that high valuations only occur during times of exuberance, which is when short-term returns are often eye-popping. The conflict which these circumstances represent, the allure of immediate gains versus the inevitability of valuation reversion, is as old as financial markets themselves.

Older still is the notion that printing money is the most palatable ready solution to seemingly intractable fiscal problems. The Great Inflation symbolically began with Lyndon Johnson lambasting Federal Reserve Chair McChesney Martin to “print the money I need” for the war in Vietnam and his Great Society programs. The fiery encounter at Johnson’s Texas ranch in December 1965 will be long remembered as part of the abject lesson of the societal costs of deficit spending funded by monetary expansion.

Today, between the monetary expansion after the financial crisis and during the pandemic, along with the ever-expanding federal deficits, we find ourselves in circumstances which carry similar risks of inflation over the long-term.

Just as Graham did in the early 1960s, astute investors today have already taken notice, as the excerpt from this Bloomberg article on June 5th covering the International Swaps and Derivatives Association meeting highlighted:

Bond industry leaders see a bleak US fiscal outlook that will keep debt growing and sustain elevated long-dated Treasury yields. Speaking during a panel discussion at the ISDA/Sifma Treasury forum in New York Wednesday, market participants said spending cuts and tax increases that would address concerns of growing Treasury debt supply remain unlikely — regardless of who wins November’s presidential election…

“No matter what the election result is, when you fast forward five to 10 years, the fiscal direction is not comfortable,” said Jason Granet, chief Investment Officer at BNY Mellon.

The amount of US Treasuries outstanding has grown to $27 trillion, up from about $12 trillion a decade ago. Last month, the Treasury left its quarterly issuance of longer-term debt unchanged, after boosting them the three previous quarters in moves that brought some auction sizes to record levels. While the Treasury said it sees no more increases for at least a few quarters, the Congressional Budget Office projects that chronic US deficits will lift the US debt to about $48 trillion by the end of 2034…

The panelists [also] said the 10-year Treasury yield in twelve months’ time likely would be hovering near current levels or up to as high as 5.25%.

In February, the Congressional Budget Office projected that interest and dividends paid to individuals will rise to $327 billion this year — more than double the amount in the mid-2010s — and keep increasing each year over the coming decade. In March alone, the Treasury Department paid out about $89 billion in interest to debt holders — or roughly $2 million a minute.

The CBO also recently projected that if current laws governing revenues and spending generally remained unchanged, the federal budget deficit would increase significantly in relation to gross domestic product over the next 30 years, driving up federal debt. Debt held by the public would soar from 99% of GDP in 2024 to 166% of GDP in 2054 — exceeding any previously recorded level and on track to increase further.

Amid the staggering numbers of the projected deficits and the growth of the national debt over the next decade, what stands out in the summary above is the underlined view of the panelists that long-term Treasury yield may be higher a year from now.

At the end of the second quarter, the financial markets also reflected the view that the long-term trajectory for yields has changed toward a higher range. A Bloomberg article on June 23rd summarized the market’s view:

Just as optimism is growing among investors that a rally in US Treasuries is about to take off, one key indicator in the bond market is flashing a worrying sign for anyone thinking about piling in….

Forward contracts referencing the five-year interest rate in the next five years — a proxy for the market’s view of where US rates might end up — have stalled at 3.6%. While that’s down from last year’s peak of 4.5%, it’s still more than one full percentage higher than the average over the past decade and above the Fed’s own estimate of 2.75%.

This matters because it means the market is pricing in a much more elevated floor for yields. The practical implication is that there are potential limits to how far bonds can run…

The prospect of higher Treasury yields a year from now, along with short-term interest rates which are projected to remain closer to 4% instead of a return to the near-zero rate regime during the decade after the financial crisis, should give all investors pause.

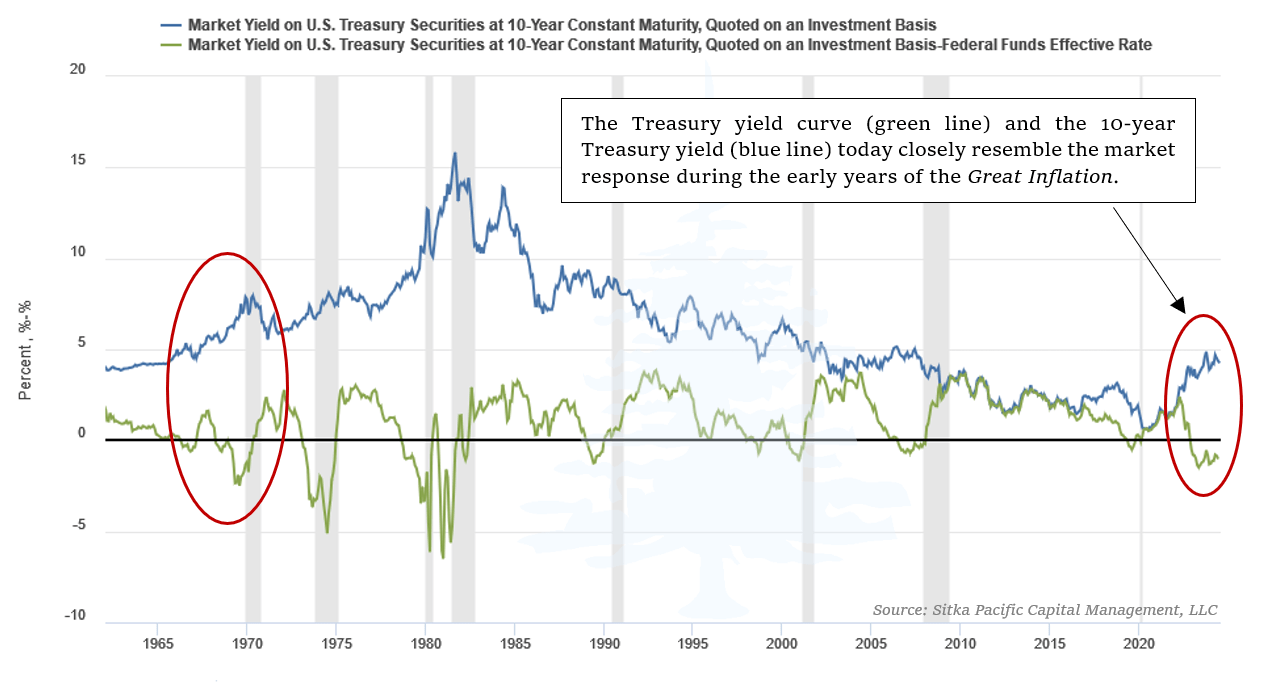

Over the past four decades, the consistent outcome following an inversion of the Treasury yield curve has been substantially lower yields across the board. These lower yields provided substantial stimulus to risk assets – especially stocks. If instead we were to see higher long-term yields in the wake of the current yield curve inversion, it would not only represent a lack of cyclical stimulus for risk assets, but it would also represent a substantial increase in the headwinds buffeting valuations. It was precisely this outcome which drove the waves of devaluation during the Great Inflation.

Higher, instead of lower, yields in the years ahead would undoubtedly be a surprising outcome for many investors, but it would not be unexpected for investors familiar with the Great Inflation.

As we reviewed in April, the long braking distance of the current Treasury yield curve inversion suggests inflation is more entrenched than at any other time since the 1970s and early 1980s. While the Federal Reserve has been squarely focused on dampening inflation over the past two years, it remains to be seen what will happen if a weakening economy forces the Fed to pivot toward supporting the other half of its dual mandate, employment. If the Fed pivots toward easing with underlying inflation still above its 2% target, the pace of inflationary price gains could re-accelerate well above its target. The increasing tension between the two halves of the Fed’s dual mandate lays bare the long-term investment value of real assets.

As Benjamin Graham observed more than a half-century ago, there are two main reasons the equity market tends to become severely overvalued: the market is in the midst of a mania, or there is a lot of inflation on the way. During the early 1970s Nifty Fifty mania, it was a combination of both.

If the Magnificent Seven mania proves to reflect both of those reasons as well, the current market environment certainly contains all the hallmarks we would expect to see. In lieu of the Bountiful Triple Dip over the past three years, investors today appear to have ventured down the same speculative path as they did a half century ago.

The lessons from the Nifty Fifty era will continue to prove their value in navigating the markets in the years ahead, particularly the lessons learned in the decade after January 1973. As investors learned quite suddenly back then, a so far, so good approach proved to be no substitute for flexible, active, historically-informed navigation of the markets.

* * *

The preceding is part of our 3rd Quarter letter to clients, which they received in July. To request a copy of the full letter, or to schedule a consultation to review your investments, visit Getting Started.

The content of this article is provided as general information and is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment or other advice. This material is not to be construed as a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any security, financial product, instrument or to participate in any particular trading strategy. Not all securities, products or services described are available in all countries, and nothing herein constitutes an offer or solicitation of any securities, products or services in any jurisdiction where their offer or sale is not qualified or exempt from registration or otherwise legally permissible.

Although the material herein is based upon information considered reliable and up-to-date, Sitka Pacific Capital Management, LLC does not assure that this material is accurate, current, or complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. Content in this article may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted, in whole or in part, without prior written consent — which is usually gladly given, as long as its use includes clear and proper attribution. Contact us for more information.

© Sitka Pacific Capital Management, LLC

In Lieu of the Bountiful Triple Dip

3rd Quarter, 2024

The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office ramped up its estimate for this year’s US budget deficit by 27% to almost $2 trillion, sounding a fresh alarm about an unprecedented trajectory for federal borrowing.

The CBO sees the deficit reaching $1.92 trillion in 2024, up from $1.69 trillion in 2023, according to updated projections released in Washington Tuesday. The new estimate is more than $400 billion larger than what the CBO anticipated in February…

~ Bloomberg, June 18, 2024

Reminds me of that fella back home who fell off a ten-story building … as he was falling, people on each floor heard him say: “So far, so good.”

~ Steve McQueen, in The Magnificent Seven

So far…so good?

* * *

When inflation begins to upend financial markets, as it has over the past few years, it represents a tremendous disruption. A transition from an era of falling inflation rates to one of higher inflation rates set off a chaotic adjustment of prices, valuations, and sentiment that cascades though financial markets and the economy. The full progression of that disruptive pivot takes time to run its course.

We have reviewed how the Great Inflation began in various articles over the past six years, and we have devoted so many pages to this topic because the last time a disruptive inflationary transition took place, Lyndon Johnson was President and McChesney Martin was head of the Federal Reserve. It was 1965, a long time ago. Many of the hard lessons investors learned during that era have largely been forgotten.

* * *

By all appearances in early 1965, inflation was nowhere in sight. Over the previous decade, inflation had averaged just 1.8% per year, and interest rates were low and stable. It was an established regime of low and stable inflation which was, on the surface, not unlike the decade prior to 2021.

Yet long before then, legendary investor Benjamin Graham had begun to wonder why the stock market appeared so overvalued by nearly every metric he tracked, but continued to relentlessly advance anyway. Early on he suspected investors were anticipating something new, or that their preferences had changed in some fundamental way. Eventually he concluded the reasons had to do with the unique aspects of the post-war experience – specifically, with inflation.

Back in 1955, Graham had testified before the United States Senate about the booming stock market. Unlike the turbulent downturn following the end of World War I, the economy and markets had soared after World War II. In the year after the end of hostilities in 1945, the Dow Jones Industrial Average quickly rose above 200, which was the first time it had reached that level since the earliest days of the Great Depression. By 1951, it had risen another 25% to above 250. And by the time Graham sat in front of the Senate Committee on Banking and Currency in March 1955, the DJIA was rapidly closing in on 500 after a near vertical rally over the previous two years.

The meteoric rise after WWII was in sharp contrast to the collapse of the market and the onset of deflation following WWI. In looking for the reasons behind the surge, Graham’s opening remarks to committee Chair J.W. Fulbright suggested he had already come to suspect that investors themselves were the main reason the markets were acting differently than they had in recent years.

A few moments into his testimony, he offered the following assessment to that effect:

With respect to the present level of stock prices, my studies lead to the impression that leading industrial stocks are not basically overvalued, but they are definitely not cheap; and they are in danger of going over into an unduly high level…

With respect to the cause of the rise in the market since September 1953, my statement indicates I would emphasize very much the change in investment and speculative sentiment, more than any change in basic economic factors…

Quantitatively, the market seems about right, but qualitatively I consider it to be on the high side and getting into a dangerous situation.

In the years after 1955, despite Graham’s assessment that the market was already “getting into a dangerous situation,” the meteoric rise continued. After consolidating near 500 in 1956, 1957, and 1958, the Dow Industrials began to rally again in 1959, and never looked back.

By 1963, with the market having quickly recovered from another brief and shallow correction earlier in the year, Graham again ventured to comment on the markets in a speech in San Francisco we reviewed in How an Inflationary End to the Bountiful Triple Dip Swindled Equity Investors. By this time, with the Dow Industrial Average trading near 800, his thinking had evolved.

Although the market’s price and valuation were higher in 1963 than in 1955, Graham was convinced investor sentiment had gone through a sea change with respect to equity market risk. Investors were now willing to pay much higher valuation multiples for common stocks than they had in the past – that much was clear. Graham reasoned this was due, in large part, to the fact that continuous inflation, without subsequent corrective episodes of deflation, had seemingly become a durable feature of the post-war economy.

* * *

As brilliant as Benjamin Graham was, he almost certainly could not have imagined how much continuous inflation lay directly ahead. Little did he know as he was speaking in the ballroom of the St. Francis Hotel in San Francisco in November 1963, events already in motion would shortly thereafter lead to the end of the second Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates, a devaluation of the equity market that would rival the value lost during the Great Depression, and a hockey-stick pivot in consumer prices that continues to this day.

The earliest hints of those looming events could be seen in the data by 1965.

The march toward the hockey-stick pivot in prices began in 1964 with a series of tax cuts, which had been proposed under the late President Kennedy in 1963, but which were passed under Lyndon Johnson. It continued with the expansion of spending related to the war in Vietnam and the new Great Society programs. Unlike the New Deal programs of Johnson’s political idol, Franklin Roosevelt, which sought to back-fill the economic void of the deflationary Great Depression, the tax cuts and the expansion of federal spending in the mid-1960s came at a time of strong economic growth and low unemployment. The result of this flood of stimulus on an already strong economy was the first significant inflationary pressures in more than a decade.

The markets took immediate notice of these new inflationary pressures, as did central banks.

The Federal Reserve began its response to rising inflationary pressures in late 1965, and immediately thereafter, Fed Chair McChesney Martin felt political pressure bear down on him from President Johnson in the form of a fiery confrontation at his Texas hill country ranch. Foreign central banks, outside of the orbit of Johnson’s infamous persuasiveness, began to convert their devaluing dollar reserves to gold to preserve value.

As a result of the expanding supply of dollars and the departure of gold, despite beginning the 1960s with enough gold to cover 85% of foreign currency reserves, the U.S. ended the 1960s with only enough to cover one quarter of those liabilities:

The nature of trends like those shown in the table above are such that they tend to slowly build over time until, one day, often quite suddenly, it causes something to break. Astute observers notice the subtle signs that things are increasingly amiss in the lead up to the break, and as a result, they are often better prepared when it happens. Yet even for the most astute observers like Graham, it is a challenging task to navigate markets during such turbulent times.

The monetary trends which led to the final end of dollar convertibility in 1971, and the Great Inflation that followed, began to subtly impact markets years beforehand. Although official inflation numbers remained benign in early 1965, as the year progressed the bond market began to take notice of the rapidly growing supply of dollars. The yield of the 10-year Treasury note began to rise late in the year, and by February 1966 it had popped up to 4.8%. This was not only a post-war high yield – it was the highest 10-year Treasury yield seen since 1921.

The same month the 10-year Treasury yield reached a new 45-year high, the stock market also took notice of the changing landscape. The high watermark of the broad equity market’s valuation that was established in early 1966 would remain unbroken until the mid-1990s, and the long, slow descent from that valuation peak over the following seventeen years would prove to be an extraordinarily difficult headwind for stock market investors.

At first, the equity market’s valuation contraction proceeded slowly, and investors began responding to the new headwind to their portfolios by starting to overweight stocks, especially those which appeared relatively immune from the impact of bond yields.

Yet as federal deficits and inflationary pressure steadily increased, bond yields rose uncomfortably high. By 1969, the yield on the 10-year Treasury had risen above 7%, and the headwinds facing the equity market strengthened. This left stock market investors with fewer and fewer attractive choices, and in their growing desperation, they began crowding into the shrinking list of stocks which were still performing well. Sensing the growing risk that year, Graham’s protégée, Warren Buffett, decided to close his investment partnerships, citing the unfavorable market environment.

What happened next is directly relevant to our circumstances today.

As yields continued to rise into 1970, bond prices fell further. By this time, bonds had increasingly become a source of aggravation and negative real returns to diversified investors – just as they have over the past four years. From 1965 to 1970, the total nominal return of bonds was negative, and the inflation-adjusted value of a diversified bond portfolio had fallen by more than 20%.

Bond investors over the past four years have had a similar, if not more severe, experience. Since 2020, when yields hit their lowest levels in history during the height of the pandemic, an investment in the longest-term Treasury bonds has lost nearly half its value. With the 21% rise in consumer prices so far this decade, the past four years now rank as the steepest loss of real, inflation-adjusted value in the history of the Treasury bond market.

During the first three years of the 1970s, bonds fell further out of favor as inflation became more entrenched. Bonds began to be viewed as “certificates of confiscation.” In lieu of bonds, investors crowded further into stocks, especially those stocks which seemed to offer protection from inflation.

By 1973, the result of this crowding was the most concentrated mania since 1929.

Stocks deemed one-decision investments at the time were those whose businesses were either resistant to inflation, or benefited from it. The reasoning at the time said that it did not matter how much an investor paid to own a part of those businesses, as with inflation rates continuously rising, there would certainly never be a time to sell them. Hence, the only decision investors had to make, the one decision to make, was to buy – at any price. “The Nifty Fifty stocks are the ones that will grow come what may, and are most insulated from the interest-rate and inflationary pressures,” reflected the sentiment at the time.

Investment managers justified owning stocks at 50-times earnings or more by pointing to their continued earnings growth despite rising inflation and high bond yields. John Bennett, of Putnum Investments, reflected this thinking. He was asked at the time how he justified owning Johnson & Johnson at 57-times earnings. Apparently with a straight face, and after a puff from his pipe, he replied: “If you look at their earnings out seven years from now, the stock’s not really that expensive.”

The equity market’s capitalization became overly concentrated in a few dozen stocks as the mania grew, but the strength of the few could not mask the growing weakness in the many. Despite the high valuations of the Nifty Fifty, the rest of the equity market was devaluing. While favored stocks like J&J rose to trade at 57-times earnings, unfavored stocks like U.S. Steel sank to 5-times earnings. “Growth” during this time outperformed “value” by a record amount, but the list of stocks deemed growth stocks was rapidly shrinking, while the list of value stocks was rapidly expanding.

At the peak of the mania, the S&P 500 index’s Cyclically-Adjusted Price-to-Earnings ratio had deflated from 24 to 18, and investors had become heavily concentrated in a few dozen winning stocks trading at extreme valuations. This gave an impressive illusion of strength to major equity market indexes. However, it was a fragile set of circumstances which then suddenly broke down after January 1973.

The Nifty-Fifty was a mania which sprouted and grew in lieu of the Bountiful Triple Dip.

Eight years after closing his investment partnerships, Warren Buffett coined the term in a Forbes column to describe the virtuous cycle that boosts equity market returns when inflation rates and bond yields are low, and the subsequent vicious cycle that begins when inflation rates and bond yields begin to rise. Investors, who after 1966 no longer enjoyed the elevated passive returns which come from expanding equity market valuations, turned to increasingly desperate speculation in seeking returns in the early 1970s, until the fragile, concentrated façade broke in 1973.

* * *

What began in the 1950s and early 1960s as an initial response to continuous inflation by investors, morphed into an irrational exuberance by the early 1970s. A half century later, we find ourselves in a market environment similar to those exuberant years between 1966 and 1973.

As bond yields have risen over the past four years, and inflation rates have become entrenched above the sub-2% readings of the 2010s, the broader equity market’s valuation has modestly deflated from its peak in 2021. However, the valuation deflation which has impacted the vast majority of stocks has been masked by a mania in a small handful of technology stocks – the Magnificent Seven. These stocks have become the close kin of the one-decision stocks of the Nifty Fifty era, as investors have again concluded no valuation is too high for these select few that appear immune from the impact of rising inflation and yields.

The excerpt below from a Bloomberg article in June of this year could have easily been written in 1973, if Johnson & Johnson, Baxter, and other high-flying stocks of the Nifty Fifty era were substituted for Apple and Nvidia:

Take out the few big tech companies that keep pushing the S&P 500 Index to all-time highs and it looks like the engine is running on fumes.

While the index is marching from one record to the next, fewer and fewer stocks are participating in this year’s rally. Nearly a third of its constituents have hit a one-month low in the past month, data compiled by Bloomberg through the end of last week show. That far outnumbers those that are pushing it higher. In fact, just 3.2% hit a one-month high, including Apple Inc. and high-flying Nvidia Corp…

“Sellers are entering the market, and bulls are dancing on the edge of a knife,” said Andrew Thrasher, a technical analyst and portfolio manager at Financial Enhancement Group. “Everything is now dependent on pretty much just Nvidia and Apple. It won’t take a whole lot to take this market down.”

As of the end of the 2nd quarter, the Magnificent Seven stocks represented an astonishing 31% of the S&P 500 index’s market capitalization. By some measures, the concentration of the major equity indexes has not been this narrow in more than half a century. At its highest price in June, the highest-flying of the Magnificent Seven traded at a stratospheric price-to-earnings ratio of 82, which means that a passive investor in the S&P 500 index is now holding an investment more concentrated in extremely overvalued stocks than at any other time since the Nifty Fifty era.

In the long run, high valuations beget low long-term returns – this is well established by centuries of market data. However, it is also true that high valuations only occur during times of exuberance, which is when short-term returns are often eye-popping. The conflict which these circumstances represent, the allure of immediate gains versus the inevitability of valuation reversion, is as old as financial markets themselves.

Older still is the notion that printing money is the most palatable ready solution to seemingly intractable fiscal problems. The Great Inflation symbolically began with Lyndon Johnson lambasting Federal Reserve Chair McChesney Martin to “print the money I need” for the war in Vietnam and his Great Society programs. The fiery encounter at Johnson’s Texas ranch in December 1965 will be long remembered as part of the abject lesson of the societal costs of deficit spending funded by monetary expansion.

Today, between the monetary expansion after the financial crisis and during the pandemic, along with the ever-expanding federal deficits, we find ourselves in circumstances which carry similar risks of inflation over the long-term.

Just as Graham did in the early 1960s, astute investors today have already taken notice, as the excerpt from this Bloomberg article on June 5th covering the International Swaps and Derivatives Association meeting highlighted:

Bond industry leaders see a bleak US fiscal outlook that will keep debt growing and sustain elevated long-dated Treasury yields. Speaking during a panel discussion at the ISDA/Sifma Treasury forum in New York Wednesday, market participants said spending cuts and tax increases that would address concerns of growing Treasury debt supply remain unlikely — regardless of who wins November’s presidential election…

“No matter what the election result is, when you fast forward five to 10 years, the fiscal direction is not comfortable,” said Jason Granet, chief Investment Officer at BNY Mellon.

The amount of US Treasuries outstanding has grown to $27 trillion, up from about $12 trillion a decade ago. Last month, the Treasury left its quarterly issuance of longer-term debt unchanged, after boosting them the three previous quarters in moves that brought some auction sizes to record levels. While the Treasury said it sees no more increases for at least a few quarters, the Congressional Budget Office projects that chronic US deficits will lift the US debt to about $48 trillion by the end of 2034…

The panelists [also] said the 10-year Treasury yield in twelve months’ time likely would be hovering near current levels or up to as high as 5.25%.

In February, the Congressional Budget Office projected that interest and dividends paid to individuals will rise to $327 billion this year — more than double the amount in the mid-2010s — and keep increasing each year over the coming decade. In March alone, the Treasury Department paid out about $89 billion in interest to debt holders — or roughly $2 million a minute.

The CBO also recently projected that if current laws governing revenues and spending generally remained unchanged, the federal budget deficit would increase significantly in relation to gross domestic product over the next 30 years, driving up federal debt. Debt held by the public would soar from 99% of GDP in 2024 to 166% of GDP in 2054 — exceeding any previously recorded level and on track to increase further.

Amid the staggering numbers of the projected deficits and the growth of the national debt over the next decade, what stands out in the summary above is the underlined view of the panelists that long-term Treasury yield may be higher a year from now.

At the end of the second quarter, the financial markets also reflected the view that the long-term trajectory for yields has changed toward a higher range. A Bloomberg article on June 23rd summarized the market’s view:

Just as optimism is growing among investors that a rally in US Treasuries is about to take off, one key indicator in the bond market is flashing a worrying sign for anyone thinking about piling in….

Forward contracts referencing the five-year interest rate in the next five years — a proxy for the market’s view of where US rates might end up — have stalled at 3.6%. While that’s down from last year’s peak of 4.5%, it’s still more than one full percentage higher than the average over the past decade and above the Fed’s own estimate of 2.75%.

This matters because it means the market is pricing in a much more elevated floor for yields. The practical implication is that there are potential limits to how far bonds can run…

The prospect of higher Treasury yields a year from now, along with short-term interest rates which are projected to remain closer to 4% instead of a return to the near-zero rate regime during the decade after the financial crisis, should give all investors pause.

Over the past four decades, the consistent outcome following an inversion of the Treasury yield curve has been substantially lower yields across the board. These lower yields provided substantial stimulus to risk assets – especially stocks. If instead we were to see higher long-term yields in the wake of the current yield curve inversion, it would not only represent a lack of cyclical stimulus for risk assets, but it would also represent a substantial increase in the headwinds buffeting valuations. It was precisely this outcome which drove the waves of devaluation during the Great Inflation.

Higher, instead of lower, yields in the years ahead would undoubtedly be a surprising outcome for many investors, but it would not be unexpected for investors familiar with the Great Inflation.

As we reviewed in April, the long braking distance of the current Treasury yield curve inversion suggests inflation is more entrenched than at any other time since the 1970s and early 1980s. While the Federal Reserve has been squarely focused on dampening inflation over the past two years, it remains to be seen what will happen if a weakening economy forces the Fed to pivot toward supporting the other half of its dual mandate, employment. If the Fed pivots toward easing with underlying inflation still above its 2% target, the pace of inflationary price gains could re-accelerate well above its target. The increasing tension between the two halves of the Fed’s dual mandate lays bare the long-term investment value of real assets.

As Benjamin Graham observed more than a half-century ago, there are two main reasons the equity market tends to become severely overvalued: the market is in the midst of a mania, or there is a lot of inflation on the way. During the early 1970s Nifty Fifty mania, it was a combination of both.

If the Magnificent Seven mania proves to reflect both of those reasons as well, the current market environment certainly contains all the hallmarks we would expect to see. In lieu of the Bountiful Triple Dip over the past three years, investors today appear to have ventured down the same speculative path as they did a half century ago.

The lessons from the Nifty Fifty era will continue to prove their value in navigating the markets in the years ahead, particularly the lessons learned in the decade after January 1973. As investors learned quite suddenly back then, a so far, so good approach proved to be no substitute for flexible, active, historically-informed navigation of the markets.

* * *

The preceding is part of our 3rd Quarter letter to clients, which they received in July. To request a copy of the full letter, or to schedule a consultation to review your investments, visit Getting Started.

The content of this article is provided as general information and is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment or other advice. This material is not to be construed as a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any security, financial product, instrument or to participate in any particular trading strategy. Not all securities, products or services described are available in all countries, and nothing herein constitutes an offer or solicitation of any securities, products or services in any jurisdiction where their offer or sale is not qualified or exempt from registration or otherwise legally permissible.

Although the material herein is based upon information considered reliable and up-to-date, Sitka Pacific Capital Management, LLC does not assure that this material is accurate, current, or complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. Content in this article may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted, in whole or in part, without prior written consent — which is usually gladly given, as long as its use includes clear and proper attribution. Contact us for more information.

© Sitka Pacific Capital Management, LLC

Investment Management

Before investing, we will discuss your goals and risk tolerances with you to see if a separately managed account at Sitka Pacific would be a good fit. To contact us for a free consultation, visit Getting Started.

Macro Value Monitor

To read a selection of recent client letters and be alerted when new letters are posted to our public site, visit Recent Client Letters.