The Dawn of Quantitative Easing and the Boom and Bust at Rue Quincampoix

By Brian McAuley

January 31, 2022

The end of the month of December, 1719, was the term of this delusion of three months. A certain number of stockjobbers, better advised than others, or more impatient to enter upon the enjoyment of their riches, combined to dispose of their shares. They took advantage of the rage which led so many to sell their estates – they purchased them, and thus obtained the real for the imaginary.

They established themselves in splendid mansions, upon magnificent domains, and made a display of their fortunes of thirty or forty millions. They possessed themselves of precious stones and jewels, which were still eagerly offered, and secured solid value in exchange for the semblance of it, which had become so prized by the crowd of dupes. The first effect of this desire to realize was a general increase in the price of everything…

– Adolphe Thiers

In the late summer of 1719, John Law finally achieved what he had long been striving for. With the creation of a flexible currency through the Banque Royale, and its widespread acceptance by the public, he had sparked an explosion of economic opportunity in France and its territories in the New World. Expanding industry and trade, along with the blooming prosperity spreading through the streets of Paris, was precisely the result Law had foreseen when he first proposed the idea of removing the monetary shackles of gold and silver fifteen years earlier, in his native Scotland.

In December 1704, after years of poor harvests and trade deficits with England, the fledgling Bank of Scotland had run out of gold and silver to redeem its paper notes — and was forced to close its doors. After the bank remained closed through the following spring, leaving farms and workers idle, the Scottish Parliament considered a proposal from Law which would create banknotes based on the value of land, so the Scottish economy would no longer be dependent on the supply of gold and silver in the bank’s vaults. Since gold and silver were prone to unpredictable fits of migration across Scotland’s borders, Law felt the value of Scotland’s land would prove a far more stable asset base for trade and commerce, a view he outlined in a book published that year, Money and Trade Considered.

Yet members of the Scottish Parliament were skeptical about basing the value of currency on anything other than gold and silver, which had for centuries been a reliable store of value. Any other foundation for money seemed speculative. After debating the proposal, they rejected Law’s plan.

In the years that followed, Law crossed the English Channel and roamed throughout the Continent, searching for a government more receptive to his monetary ideas. He lived in Brussels for a time, traveled throughout the Netherlands, Germany and France, and then eventually settled in Genoa, Italy. There he earned his living in gaming rooms not far from the esteemed Genoese banking houses, and he proposed plans for new banking institutions to many he met. However, despite Law’s claims about the prosperity that awaited those who unleashed their economies from the monetary governor of gold and silver, none of the princes and kings he spoke with throughout Europe were interested in abandoning the stable foundation of their money.

Then, in September 1715, King Louis XIV died, and the new regent of France found himself in charge of a government that was effectively bankrupt after the king’s opulent 72-year reign: Louis XIV left France with 2,818 million livres (mL) of debt. The debt was composed of 1,068mL of perpetual annuities, 830mL of official offices that had been purchased by the nobility, and 920mL of floating rate debt. The annuities and sold offices required 86.5mL a year in payments, and the floating rate debt required another 40mL per year — for a total of 126.5mL a year in interest payments. However, the government was only taking in 166mL in taxes, and 71mL of that income was consumed by other spending — leaving a primary surplus of only 95mL to cover 126.5mL in annual interest payments.

It was clearly an unsustainable and precarious fiscal situation, and there were no readily apparent solutions. Raising taxes or cutting spending in the amounts required to close the 31.5mL annual deficit would likely result in unmitigated chaos throughout France, and a default would likely result in an open revolt by the nobility, to whom most of France’s debt was owed. Memories were still fresh of the nobles’ revolt decades before during La Frondé, which had been sparked by an increase in taxes on the nobles’ privileged interests.

John Law’s monetary ideas had evolved since his appearance before the Scottish Parliament in 1704, and the regent was aware of Law’s banking proposals floating around Genoa; the regent and Law had first met years before, when the regent was still the duc de Chartres. By 1715, Law wanted to establish a bank, modeled on the Bank of Amsterdam, which would issue currency backed by gold and silver while also handling the government’s debt service. Louis XIV had rejected the idea before his death, as he felt any currency in place of gold and silver coin to be questionable. But the regent, desperate for creative solutions, summoned Law to court again — and this time Law found a receptive audience.

The regent permitted Law to establish a private bank in May 1716, the Banque Générale. The bank would take in gold and silver as deposits, and issue paper notes which would be redeemable in coin on demand. The notes would be 100% backed by the gold and silver in the bank’s vaults. The bank would be initially capitalized by selling 1200 shares at 5000 livres each, which could be purchased by investors with a combination of cash and government debt. Law bought a quarter of the shares, and the regent bought nearly a quarter in the name of the young king, which established the bank with capital of 75% government bonds and 25% gold and silver coin.

Since the bank’s notes represented a legal claim on gold livres held securely in the bank, those who accepted the notes in public transactions no longer had to worry whether coins they accepted as payment were counterfeit — which was always a risk with coin transactions. As a result of this key advantage, which had been at the foundation of the Bank of Amsterdam’s success over the prior century, the notes quickly became a preferred method of payment.

Along with the security of being fully backed by gold and silver, the bank’s notes and shares were also made more attractive by the regent’s actions. He ordered a recoinage, which reduced the amount of gold in every livre-denominated coin by 20%. Then, in a series of partial defaults, the regent reduced the value of certain government bonds in October 1715, reduced the payments to sold offices in January 1716, on floating rate debt in April, and on annuities in June. This reduced the government’s debt service payments by 7mL a year. The regent then converted the government’s floating rate debt to bearer notes (billets d’État), which came with a 4% interest rate, no defined redemption date, and no specific backing. The bearer notes traded at 36% of their face value in mid-1716 after they were issued with such weak backing — but they could be used to purchase shares of the Banque Générale at par value. As a result, the bank’s 1200 shares were quickly subscribed, and gold and silver coin, along with billets d’ État, flooded into the Banque Générale’s vaults and were exchanged for bank notes and shares.

As the bank’s deposits increased, so did the volume of paper livres circulating throughout France. The Banque Générale issued 40–50 million livres of bank notes annually between 1716 and 1718, and they quickly began to displace coin for official business. In October 1716, tax collectors were required to take the notes as payment, and in April 1717 the notes became required to pay all taxes. Then in September 1717, the royal accountants began keeping all government records and receipts, and made all payments, in paper livres issued by the bank.

By 1718, the bank had been so successful in transforming France’s financial infrastructure that the regent and Law decided to nationalize it by buying out all shareholders in the name of the king. Existing shareholders were bought out at the par value of 5000L per share. For shareholders who paid for their shares with gold and discounted billets d’État in 1715, their total return, including dividends, came to 115% on their investment in only three years — a rate of return almost unheard of at the time. This established Law’s reputation as someone to bet on.

When all the outstanding shares had been purchased in the name of the king by December 1718, the Banque Générale officially became the Banque Royale. For the first time, the regent found himself with a printing press at the government’s disposal, and the presses set to work almost immediately. While the Banque Générale had issued banknotes at a rate of 40–50mL per year leading up to 1719, the Banque Royale began by issuing that many banknotes in its first month — and the pace accelerated from there.

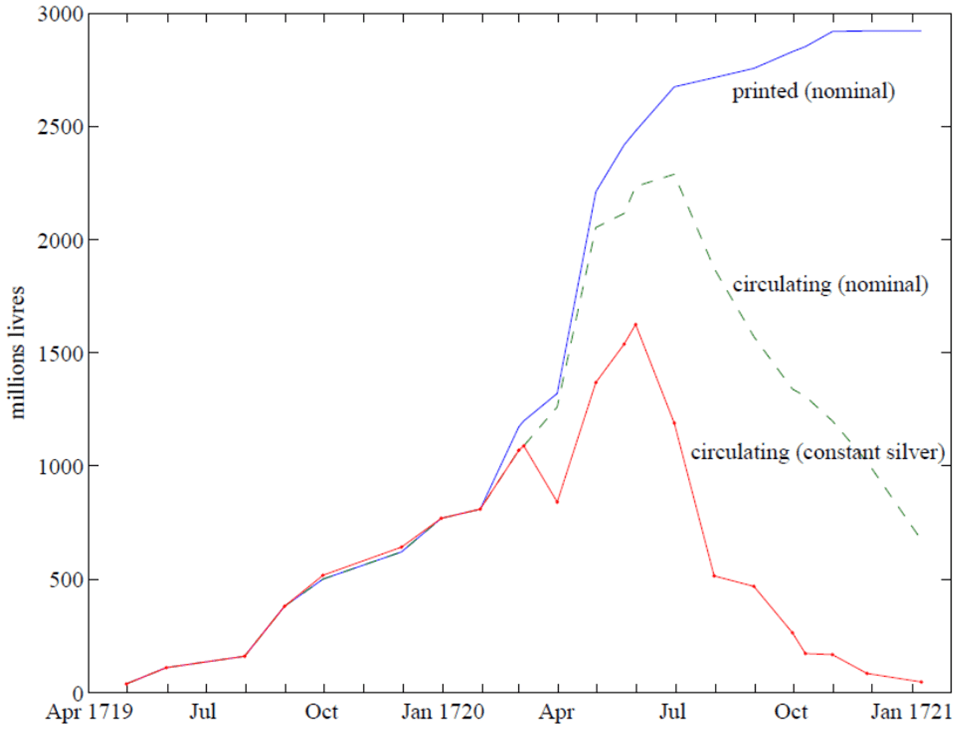

In April 1719, the Banque Royale issued 28mL in 1000L denominated notes, along with 10mL in 100L notes — for a total of 38mL. The following month, the bank issued 109.9mL in notes. By September, the rate of new note issuance had reached 500.6mL, and in December the bank issued 769mL in new notes, including 332.9mL in new 10,000-livre denominated notes. By the end of 1719, the value of paper banknotes circulating throughout France had climbed twenty-fold to nearly one billion livres.

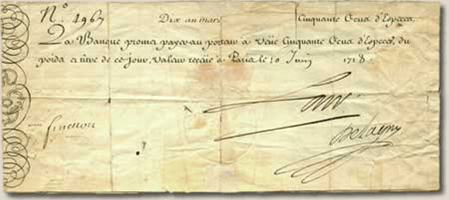

There was a critical, but little noticed change which allowed the expansion of the supply of paper banknotes in 1719. One of the main reasons the notes of the Banque Générale had gained widespread acceptance was that they could be redeemed for a specified amount of gold or silver livres: printed on every banknote was a guarantee that it could be brought into the bank and converted in coin. For example, a 500L note issued from the Banque Générale in 1718 read “the Bank promises to pay on sight to the bearer 100 écus of the weight and fineness of this day,” the écu being a specific amount of silver. With that guarantee, the public confidently deposited their gold and silver into the vaults of the Banque Générale, knowing the notes they received in exchange were convertible any time they chose.

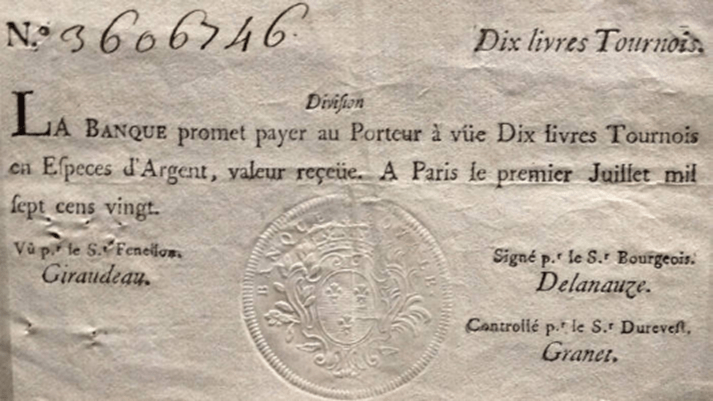

The notes of the Banque Royale, however, contained a guarantee that they were legal tender for their denominated number of livres, but there was no guarantee that they could be converted into a specific amount of gold or silver. Those holding the notes were thus in possession of a commitment from the king that they would be accepted as payment, but no guarantee of their real value in gold and silver.

The public hardly noticed. By 1719, banknotes had replaced coins in nearly all everyday transactions, from buying bread to paying taxes. In addition, the value of shares in Law’s newest venture were traded in banknotes as well — and the public was clamoring for part of the action.

In the wake of the successful launch of the Banque Générale, Law had formed a private trading company in 1717, the Compagnie d’Occident (Company of the West), to develop the Mississippi territory in North America. The French colony of Louisiana, representing 41% of the present-day continental United States and named after the late Louis XIV, had been a French colony for forty years. Yet in 1717 only 500 Europeans lived in the entire territory, and it had never been developed enough to return any profit to France. Law acquired a monopoly for the Company of the West to develop and trade with the territory, and he set to work putting his plan into action.

An IPO was opened on September 14, 1717, to attract capital for the development of Louisiana and other ventures Law wanted the Company to pursue. Unlike the launch of the Banque Générale, investors could buy shares solely with government debt, billets d’État. Subscriptions for the shares were slow, however, and over the first two weeks only 28mL of the 100mL IPO was purchased — and 13.3mL had been purchased by Law himself. In June 1718, a payment option was introduced where investors could put 20% down and pay the rest within five months, and this stimulated just enough demand to sell all 100mL of the shares by the end of 1718.

However, the tepid initial demand for the shares in 1718 surged dramatically in 1719. In the spring and early summer, Law had announced a series of mergers and new businesses for the Company of the West. He first moved to combine the trading operations with two other existing French trading companies, the Compagnie des Indes Orientales and the Compagnie de Chine. He set an additional share offering to recapitalize those companies under the Company of the West and to begin building a fleet of long-haul, 500-ton vessels. The initial shares of the Company of the West were offered at 490 livres throughout 1718, but Law offered the new shares at 550 livres in May of 1719, and the new offering was not only fully subscribed, but the shares were immediately bid up to 600 livres on rue Quincampoix.

In the early months of 1719, a secondary market for Company of the West shares had spung up on rue Quincampoix, a short, narrow street on the right bank in Paris, where the Banque Royale was headquartered. Traders had begun inundating the street during the day while waiting for news to come out of the bank, buying or selling their Company shares in response to any perceived change in the Company’s fortunes. Rents for space along the street soared as merchants established trading houses, shops and cafes to capitalize on the traders’ growing exuberance.

Yet the growing frenzy for the shares was not fueled primarily by Law’s acquisition announcements that spring, but by the growing monetary flood from the Banque Royale. There had been four banknote issues in the first four months of the year, on January 10, February 15, and the 1st and 28th of April; a total of 110 livres of new banknotes had been issued by the Banque Royale in just four months. Then on May 7, Law announced another devaluation of the gold livre coin, which induced a new surge in demand for more banknotes, and the Banque Royale’s printing press responded.

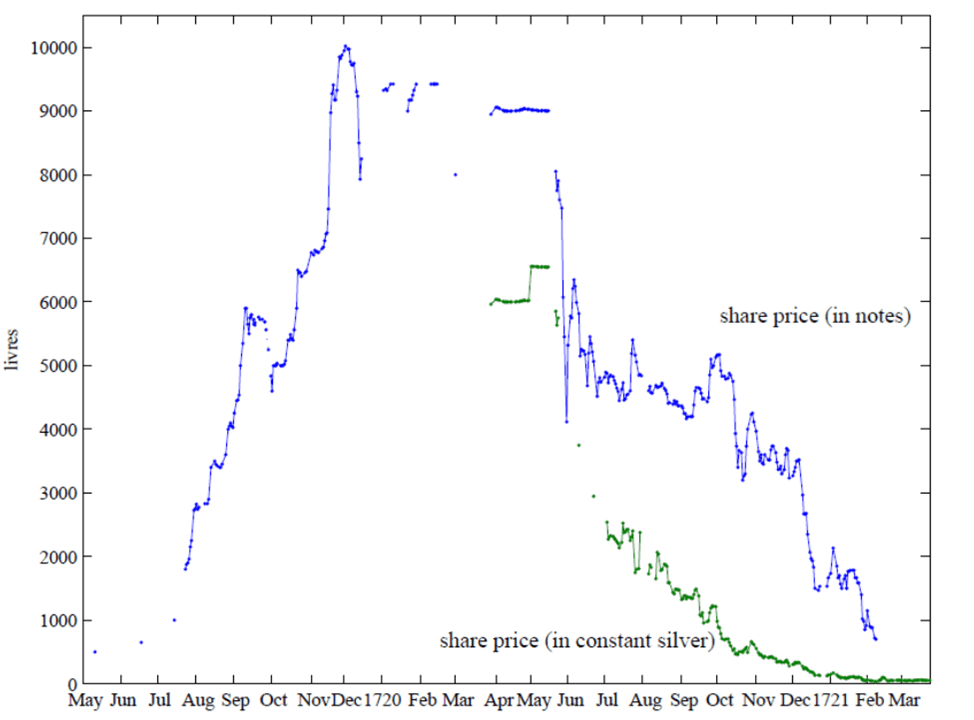

Yet the monetary-fueled rise to 600 livres a share in May was just the beginning. In July, Law announced the Company of the West was taking over trade with Africa, and also operation of the Royal Mints. These announcements were coupled with 50mL of new banknotes from the Banque Royale in July, and the shares of the Company of the West surged above 1000 livres on July 21. The bank then issued another 220mL in new banknotes in August, 120mL in September, 120mL in October and November, and 148mL in December. As the new notes flooded out into the rue Quincampoix, Company of the West shares soared. By the end of 1719, the Banque Royale had issued 810mL in banknotes, and the Company of the West was valued more highly than the entire French economy.

The twenty-fold surge of Company of the West shares to 10,000 livres in 1719 was fueled by a twenty-fold increase in the supply of Banque Royale notes, and the shares were not the only price rising in France. Property prices had risen so high that rental yields in Paris fell to just 2%, and even wealthy citizens in Paris and throughout the rest of France found themselves no longer able to afford a home. The cost of basic commodities was rising as well. The price of meat and grain surged, and the exchange rate of the livre with other currencies throughout Europe began to decline — making foreign imports more expensive. Throughout France it was becoming increasingly difficult to meet daily expenses.

* * *

The end of the boom arrived when the first trickle out of banknotes back to gold and silver began.

Law had announced a series of decrees in 1719 that progressively restricted the use of gold and silver to small transactions, and by December 1719 it was illegal to make a payment larger than 300 livres in gold or 10 livres in silver. In February 1720, as the supply of banknotes reached 1 billion livres, it was made illegal to own more than 500L in gold, in any form. Then in April, when the money supply had doubled again to 2 billion livres, all gold and silver clauses in contracts were voided by royal decree.

By that time, however, the price of gold and silver had begun rising as Parisians began to sell their Company of the West shares and banknotes for any portable real asset. Law found himself having to issue more and more banknotes just to keep the share price of the Company of the West aloft and confidence in the notes intact, but once the first cracks in sentiment began to widen, no amount of new banknotes or decrees was enough stem the exodus back into real assets.

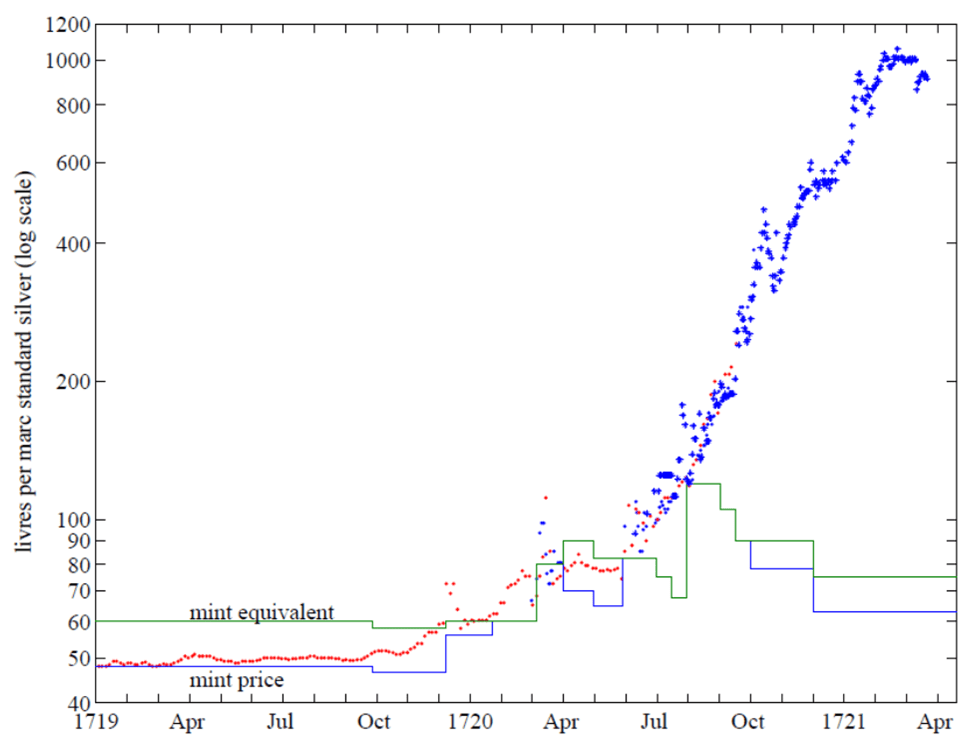

There was a run on the Banque Royale on the last day of November 1719, and the next day Law was forced to issue a decree that all public payments were to be made in banknotes — not gold and silver. This ended the run on the bank on December 1st, but the event proved to be an awakening. The price of gold and silver continued to trend higher through early 1720, with a marc of silver reaching 80 livres. This was only a modest increase from the 50 livres a marc of silver had traded at throughout the twenty-fold expansion of the Banque Royale’s money supply in 1719, but as panic set in, the price of gold and silver began to rapidly catch up to the expanded supply of paper livres.

Law then realized that in order to restore confidence in the notes of the Banque Royale, he would have to shrink the supply of banknotes and devalue the shares of the Company of the West to bring them in line with the supply of gold and silver. When the supply of notes from the Banque Royale had climbed to 2.2 billion livres in May, it was more than twice Law’s estimate of the value of gold and silver in France. He issued a decree on May 21, 1720, announcing a steady reduction in the value of the Company of the West shares from the then current 9000 livres a share to 5000 livres by the end of the year, along with a concurrent reduction in the supply of Banque Royale notes. In Law’s rational mind, this would restore the balance between paper assets and real assets to a more sustainable equilibrium.

The impact of the decree on the rue Quincampoix, however, was anything but rational or stable. Panicked Parisians rushed to convert their banknotes into gold and silver, and they sold every asset that was denominated in banknotes to do so, including Company of West shares.

When the Banque Royale was slow to open a few days later on May 25th, an angry mob threw stones at the windows of the bank until it did. There were few bids for Company of the West shares on rue Quincampoix, but what transactions did take place occurred at prices below 5000 livres a share — half what they had traded at prior to May 21. Shareholders were furious at losing half their wealth. Rumors then abounded that the Banque Royale did not have any more gold and silver to exchange for banknotes, and the bank was closed on May 31 so an inspector could examine the books. The inspector assured the public that the bank was in decent shape and that there was “plenty” of gold and silver to continue redemptions of banknotes, but when the bank was reopened, the panicked redemptions resumed.

To quell the panic, a new edict was issued on June 1st that permitted citizens to own as much gold and silver as they desired, reversing the restrictions that had been put in place beginning in 1719. Over the next six months, banknotes were abandoned wholesale for the safety and security of gold and silver, and assets denominated in banknotes lost nearly all of their real value; the price of a marc of silver climbed from 80 livres in April to over 1000 livres in early 1721, and shares of the Company of the West fell back below 1000 livres per share.

By the end of 1721, rue Quincampoix had returned to the quiet street it was before the boom, as the traders outside the Banque Royale had all but disappeared. Law had fled back to Italy. In Louisiana, another 500 settlers had arrived at the end of 1720, some of them against their will, which brought the total number of Europeans in the territory to 1000. However, the Company of the West never realized a profit from Louisiana before the boom in the shares had turned into a bust.

* * *

The above is part 1 of Volume I Issue I of The Macro Value Monitor, a publication focusing on Monetary History, Market Myths, Investing Legends, and Real Global Value. Part II, An Exuberance All Too Familiar Amid a Modern Monetary Bubble, is available on Substack.

The content of this document is provided as general information and is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment or other advice. This material is not to be construed as a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any security, financial product, instrument or to participate in any particular trading strategy. Not all securities, products or services described are available in all countries, and nothing herein constitutes an offer or solicitation of any securities, products or services in any jurisdiction where their offer or sale is not qualified or exempt from registration or otherwise legally permissible.

Although the material herein is based upon information considered reliable and up-to-date, Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC does not assure that this material is accurate, current, or complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. Content in this document may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted, in whole or in part, without prior written consent from Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC — which is usually gladly given, as long as its use includes clear and proper attribution. Contact us for more information.

© Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC

The Dawn of Quantitative Easing and the Boom and Bust at Rue Quincampoix

By Brian McAuley

January 31, 2022

The end of the month of December, 1719, was the term of this delusion of three months. A certain number of stockjobbers, better advised than others, or more impatient to enter upon the enjoyment of their riches, combined to dispose of their shares. They took advantage of the rage which led so many to sell their estates – they purchased them, and thus obtained the real for the imaginary.

They established themselves in splendid mansions, upon magnificent domains, and made a display of their fortunes of thirty or forty millions. They possessed themselves of precious stones and jewels, which were still eagerly offered, and secured solid value in exchange for the semblance of it, which had become so prized by the crowd of dupes. The first effect of this desire to realize was a general increase in the price of everything…

– Adolphe Thiers

In the late summer of 1719, John Law finally achieved what he had long been striving for. With the creation of a flexible currency through the Banque Royale, and its widespread acceptance by the public, he had sparked an explosion of economic opportunity in France and its territories in the New World. Expanding industry and trade, along with the blooming prosperity spreading through the streets of Paris, was precisely the result Law had foreseen when he first proposed the idea of removing the monetary shackles of gold and silver fifteen years earlier, in his native Scotland.

In December 1704, after years of poor harvests and trade deficits with England, the fledgling Bank of Scotland had run out of gold and silver to redeem its paper notes — and was forced to close its doors. After the bank remained closed through the following spring, leaving farms and workers idle, the Scottish Parliament considered a proposal from Law which would create banknotes based on the value of land, so the Scottish economy would no longer be dependent on the supply of gold and silver in the bank’s vaults. Since gold and silver were prone to unpredictable fits of migration across Scotland’s borders, Law felt the value of Scotland’s land would prove a far more stable asset base for trade and commerce, a view he outlined in a book published that year, Money and Trade Considered.

Yet members of the Scottish Parliament were skeptical about basing the value of currency on anything other than gold and silver, which had for centuries been a reliable store of value. Any other foundation for money seemed speculative. After debating the proposal, they rejected Law’s plan.

In the years that followed, Law crossed the English Channel and roamed throughout the Continent, searching for a government more receptive to his monetary ideas. He lived in Brussels for a time, traveled throughout the Netherlands, Germany and France, and then eventually settled in Genoa, Italy. There he earned his living in gaming rooms not far from the esteemed Genoese banking houses, and he proposed plans for new banking institutions to many he met. However, despite Law’s claims about the prosperity that awaited those who unleashed their economies from the monetary governor of gold and silver, none of the princes and kings he spoke with throughout Europe were interested in abandoning the stable foundation of their money.

Then, in September 1715, King Louis XIV died, and the new regent of France found himself in charge of a government that was effectively bankrupt after the king’s opulent 72-year reign: Louis XIV left France with 2,818 million livres (mL) of debt. The debt was composed of 1,068mL of perpetual annuities, 830mL of official offices that had been purchased by the nobility, and 920mL of floating rate debt. The annuities and sold offices required 86.5mL a year in payments, and the floating rate debt required another 40mL per year — for a total of 126.5mL a year in interest payments. However, the government was only taking in 166mL in taxes, and 71mL of that income was consumed by other spending — leaving a primary surplus of only 95mL to cover 126.5mL in annual interest payments.

It was clearly an unsustainable and precarious fiscal situation, and there were no readily apparent solutions. Raising taxes or cutting spending in the amounts required to close the 31.5mL annual deficit would likely result in unmitigated chaos throughout France, and a default would likely result in an open revolt by the nobility, to whom most of France’s debt was owed. Memories were still fresh of the nobles’ revolt decades before during La Frondé, which had been sparked by an increase in taxes on the nobles’ privileged interests.

John Law’s monetary ideas had evolved since his appearance before the Scottish Parliament in 1704, and the regent was aware of Law’s banking proposals floating around Genoa; the regent and Law had first met years before, when the regent was still the duc de Chartres. By 1715, Law wanted to establish a bank, modeled on the Bank of Amsterdam, which would issue currency backed by gold and silver while also handling the government’s debt service. Louis XIV had rejected the idea before his death, as he felt any currency in place of gold and silver coin to be questionable. But the regent, desperate for creative solutions, summoned Law to court again — and this time Law found a receptive audience.

The regent permitted Law to establish a private bank in May 1716, the Banque Générale. The bank would take in gold and silver as deposits, and issue paper notes which would be redeemable in coin on demand. The notes would be 100% backed by the gold and silver in the bank’s vaults. The bank would be initially capitalized by selling 1200 shares at 5000 livres each, which could be purchased by investors with a combination of cash and government debt. Law bought a quarter of the shares, and the regent bought nearly a quarter in the name of the young king, which established the bank with capital of 75% government bonds and 25% gold and silver coin.

Since the bank’s notes represented a legal claim on gold livres held securely in the bank, those who accepted the notes in public transactions no longer had to worry whether coins they accepted as payment were counterfeit — which was always a risk with coin transactions. As a result of this key advantage, which had been at the foundation of the Bank of Amsterdam’s success over the prior century, the notes quickly became a preferred method of payment.

Along with the security of being fully backed by gold and silver, the bank’s notes and shares were also made more attractive by the regent’s actions. He ordered a recoinage, which reduced the amount of gold in every livre-denominated coin by 20%. Then, in a series of partial defaults, the regent reduced the value of certain government bonds in October 1715, reduced the payments to sold offices in January 1716, on floating rate debt in April, and on annuities in June. This reduced the government’s debt service payments by 7mL a year. The regent then converted the government’s floating rate debt to bearer notes (billets d’État), which came with a 4% interest rate, no defined redemption date, and no specific backing. The bearer notes traded at 36% of their face value in mid-1716 after they were issued with such weak backing — but they could be used to purchase shares of the Banque Générale at par value. As a result, the bank’s 1200 shares were quickly subscribed, and gold and silver coin, along with billets d’ État, flooded into the Banque Générale’s vaults and were exchanged for bank notes and shares.

As the bank’s deposits increased, so did the volume of paper livres circulating throughout France. The Banque Générale issued 40–50 million livres of bank notes annually between 1716 and 1718, and they quickly began to displace coin for official business. In October 1716, tax collectors were required to take the notes as payment, and in April 1717 the notes became required to pay all taxes. Then in September 1717, the royal accountants began keeping all government records and receipts, and made all payments, in paper livres issued by the bank.

By 1718, the bank had been so successful in transforming France’s financial infrastructure that the regent and Law decided to nationalize it by buying out all shareholders in the name of the king. Existing shareholders were bought out at the par value of 5000L per share. For shareholders who paid for their shares with gold and discounted billets d’État in 1715, their total return, including dividends, came to 115% on their investment in only three years — a rate of return almost unheard of at the time. This established Law’s reputation as someone to bet on.

When all the outstanding shares had been purchased in the name of the king by December 1718, the Banque Générale officially became the Banque Royale. For the first time, the regent found himself with a printing press at the government’s disposal, and the presses set to work almost immediately. While the Banque Générale had issued banknotes at a rate of 40–50mL per year leading up to 1719, the Banque Royale began by issuing that many banknotes in its first month — and the pace accelerated from there.

In April 1719, the Banque Royale issued 28mL in 1000L denominated notes, along with 10mL in 100L notes — for a total of 38mL. The following month, the bank issued 109.9mL in notes. By September, the rate of new note issuance had reached 500.6mL, and in December the bank issued 769mL in new notes, including 332.9mL in new 10,000-livre denominated notes. By the end of 1719, the value of paper banknotes circulating throughout France had climbed twenty-fold to nearly one billion livres.

There was a critical, but little noticed change which allowed the expansion of the supply of paper banknotes in 1719. One of the main reasons the notes of the Banque Générale had gained widespread acceptance was that they could be redeemed for a specified amount of gold or silver livres: printed on every banknote was a guarantee that it could be brought into the bank and converted in coin. For example, a 500L note issued from the Banque Générale in 1718 read “the Bank promises to pay on sight to the bearer 100 écus of the weight and fineness of this day,” the écu being a specific amount of silver. With that guarantee, the public confidently deposited their gold and silver into the vaults of the Banque Générale, knowing the notes they received in exchange were convertible any time they chose.

The notes of the Banque Royale, however, contained a guarantee that they were legal tender for their denominated number of livres, but there was no guarantee that they could be converted into a specific amount of gold or silver. Those holding the notes were thus in possession of a commitment from the king that they would be accepted as payment, but no guarantee of their real value in gold and silver.

The public hardly noticed. By 1719, banknotes had replaced coins in nearly all everyday transactions, from buying bread to paying taxes. In addition, the value of shares in Law’s newest venture were traded in banknotes as well — and the public was clamoring for part of the action.

In the wake of the successful launch of the Banque Générale, Law had formed a private trading company in 1717, the Compagnie d’Occident (Company of the West), to develop the Mississippi territory in North America. The French colony of Louisiana, representing 41% of the present-day continental United States and named after the late Louis XIV, had been a French colony for forty years. Yet in 1717 only 500 Europeans lived in the entire territory, and it had never been developed enough to return any profit to France. Law acquired a monopoly for the Company of the West to develop and trade with the territory, and he set to work putting his plan into action.

An IPO was opened on September 14, 1717, to attract capital for the development of Louisiana and other ventures Law wanted the Company to pursue. Unlike the launch of the Banque Générale, investors could buy shares solely with government debt, billets d’État. Subscriptions for the shares were slow, however, and over the first two weeks only 28mL of the 100mL IPO was purchased — and 13.3mL had been purchased by Law himself. In June 1718, a payment option was introduced where investors could put 20% down and pay the rest within five months, and this stimulated just enough demand to sell all 100mL of the shares by the end of 1718.

However, the tepid initial demand for the shares in 1718 surged dramatically in 1719. In the spring and early summer, Law had announced a series of mergers and new businesses for the Company of the West. He first moved to combine the trading operations with two other existing French trading companies, the Compagnie des Indes Orientales and the Compagnie de Chine. He set an additional share offering to recapitalize those companies under the Company of the West and to begin building a fleet of long-haul, 500-ton vessels. The initial shares of the Company of the West were offered at 490 livres throughout 1718, but Law offered the new shares at 550 livres in May of 1719, and the new offering was not only fully subscribed, but the shares were immediately bid up to 600 livres on rue Quincampoix.

In the early months of 1719, a secondary market for Company of the West shares had spung up on rue Quincampoix, a short, narrow street on the right bank in Paris, where the Banque Royale was headquartered. Traders had begun inundating the street during the day while waiting for news to come out of the bank, buying or selling their Company shares in response to any perceived change in the Company’s fortunes. Rents for space along the street soared as merchants established trading houses, shops and cafes to capitalize on the traders’ growing exuberance.

Yet the growing frenzy for the shares was not fueled primarily by Law’s acquisition announcements that spring, but by the growing monetary flood from the Banque Royale. There had been four banknote issues in the first four months of the year, on January 10, February 15, and the 1st and 28th of April; a total of 110 livres of new banknotes had been issued by the Banque Royale in just four months. Then on May 7, Law announced another devaluation of the gold livre coin, which induced a new surge in demand for more banknotes, and the Banque Royale’s printing press responded.

Yet the monetary-fueled rise to 600 livres a share in May was just the beginning. In July, Law announced the Company of the West was taking over trade with Africa, and also operation of the Royal Mints. These announcements were coupled with 50mL of new banknotes from the Banque Royale in July, and the shares of the Company of the West surged above 1000 livres on July 21. The bank then issued another 220mL in new banknotes in August, 120mL in September, 120mL in October and November, and 148mL in December. As the new notes flooded out into the rue Quincampoix, Company of the West shares soared. By the end of 1719, the Banque Royale had issued 810mL in banknotes, and the Company of the West was valued more highly than the entire French economy.

The twenty-fold surge of Company of the West shares to 10,000 livres in 1719 was fueled by a twenty-fold increase in the supply of Banque Royale notes, and the shares were not the only price rising in France. Property prices had risen so high that rental yields in Paris fell to just 2%, and even wealthy citizens in Paris and throughout the rest of France found themselves no longer able to afford a home. The cost of basic commodities was rising as well. The price of meat and grain surged, and the exchange rate of the livre with other currencies throughout Europe began to decline — making foreign imports more expensive. Throughout France it was becoming increasingly difficult to meet daily expenses.

* * *

The end of the boom arrived when the first trickle out of banknotes back to gold and silver began.

Law had announced a series of decrees in 1719 that progressively restricted the use of gold and silver to small transactions, and by December 1719 it was illegal to make a payment larger than 300 livres in gold or 10 livres in silver. In February 1720, as the supply of banknotes reached 1 billion livres, it was made illegal to own more than 500L in gold, in any form. Then in April, when the money supply had doubled again to 2 billion livres, all gold and silver clauses in contracts were voided by royal decree.

By that time, however, the price of gold and silver had begun rising as Parisians began to sell their Company of the West shares and banknotes for any portable real asset. Law found himself having to issue more and more banknotes just to keep the share price of the Company of the West aloft and confidence in the notes intact, but once the first cracks in sentiment began to widen, no amount of new banknotes or decrees was enough stem the exodus back into real assets.

There was a run on the Banque Royale on the last day of November 1719, and the next day Law was forced to issue a decree that all public payments were to be made in banknotes — not gold and silver. This ended the run on the bank on December 1st, but the event proved to be an awakening. The price of gold and silver continued to trend higher through early 1720, with a marc of silver reaching 80 livres. This was only a modest increase from the 50 livres a marc of silver had traded at throughout the twenty-fold expansion of the Banque Royale’s money supply in 1719, but as panic set in, the price of gold and silver began to rapidly catch up to the expanded supply of paper livres.

Law then realized that in order to restore confidence in the notes of the Banque Royale, he would have to shrink the supply of banknotes and devalue the shares of the Company of the West to bring them in line with the supply of gold and silver. When the supply of notes from the Banque Royale had climbed to 2.2 billion livres in May, it was more than twice Law’s estimate of the value of gold and silver in France. He issued a decree on May 21, 1720, announcing a steady reduction in the value of the Company of the West shares from the then current 9000 livres a share to 5000 livres by the end of the year, along with a concurrent reduction in the supply of Banque Royale notes. In Law’s rational mind, this would restore the balance between paper assets and real assets to a more sustainable equilibrium.

The impact of the decree on the rue Quincampoix, however, was anything but rational or stable. Panicked Parisians rushed to convert their banknotes into gold and silver, and they sold every asset that was denominated in banknotes to do so, including Company of West shares.

When the Banque Royale was slow to open a few days later on May 25th, an angry mob threw stones at the windows of the bank until it did. There were few bids for Company of the West shares on rue Quincampoix, but what transactions did take place occurred at prices below 5000 livres a share — half what they had traded at prior to May 21. Shareholders were furious at losing half their wealth. Rumors then abounded that the Banque Royale did not have any more gold and silver to exchange for banknotes, and the bank was closed on May 31 so an inspector could examine the books. The inspector assured the public that the bank was in decent shape and that there was “plenty” of gold and silver to continue redemptions of banknotes, but when the bank was reopened, the panicked redemptions resumed.

To quell the panic, a new edict was issued on June 1st that permitted citizens to own as much gold and silver as they desired, reversing the restrictions that had been put in place beginning in 1719. Over the next six months, banknotes were abandoned wholesale for the safety and security of gold and silver, and assets denominated in banknotes lost nearly all of their real value; the price of a marc of silver climbed from 80 livres in April to over 1000 livres in early 1721, and shares of the Company of the West fell back below 1000 livres per share.

By the end of 1721, rue Quincampoix had returned to the quiet street it was before the boom, as the traders outside the Banque Royale had all but disappeared. Law had fled back to Italy. In Louisiana, another 500 settlers had arrived at the end of 1720, some of them against their will, which brought the total number of Europeans in the territory to 1000. However, the Company of the West never realized a profit from Louisiana before the boom in the shares had turned into a bust.

* * *

The above is part 1 of Volume I Issue I of The Macro Value Monitor, a publication focusing on Monetary History, Market Myths, Investing Legends, and Real Global Value. Part II, An Exuberance All Too Familiar Amid a Modern Monetary Bubble, is available on Substack.

The content of this document is provided as general information and is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment or other advice. This material is not to be construed as a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any security, financial product, instrument or to participate in any particular trading strategy. Not all securities, products or services described are available in all countries, and nothing herein constitutes an offer or solicitation of any securities, products or services in any jurisdiction where their offer or sale is not qualified or exempt from registration or otherwise legally permissible.

Although the material herein is based upon information considered reliable and up-to-date, Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC does not assure that this material is accurate, current, or complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. Content in this document may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted, in whole or in part, without prior written consent from Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC — which is usually gladly given, as long as its use includes clear and proper attribution. Contact us for more information.

© Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC

Investment Management

Before investing, we will discuss your goals and risk tolerances with you to see if a separately managed account at Sitka Pacific would be a good fit. To contact us for a free consultation, visit Getting Started.

Macro Value Monitor

To read a selection of recent client letters and be alerted when new letters are posted to our public site, visit Recent Client Letters.