The 1965 Pivot and a Rhyme of History

You went ahead and did something that you knew I disapproved of, that can affect my entire term here. You took advantage of me and I’m not going to forget it…You’ve got me into a position where you can run a rapier into me and you’ve run it.

Martin, my boys are dying in Vietnam, and you won’t print the money I need.

– President Lyndon Johnson to Fed Chairman William McChesney Martin, December 6, 1965

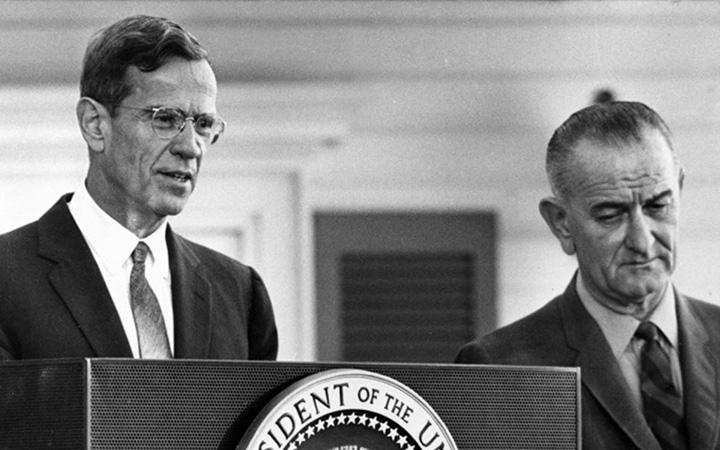

William McChesney Martin and Lyndon Johnson outside Johnson’s Texas ranch.

The study of history can be a surreal experience. Any look back at past events comes with the knowledge of many things which did or did not unfold afterwards, and this inevitably puts the events into a dreamlike context when they are looked at long after they happened. Some decisions and actions look prophetic, while others appear predictably tragic. Still others look much more intentional than they really were.

It is easy to make judgements from a safe perch in the future, which comes only after we know how things turned out. Yet it is not so easy to imagine what it would have been like to live through some period in history without knowing how the future would unfold. But it is a great challenge. Suspending any judgement stemming from our privileged place in the future while looking at history must be an exercise in vigilance and perseverance, if we are to distill the lessons relevant to our present time. Otherwise, we will fail to appreciate just how and why decisions are made, and how we can do better in the future.

The 1960s is a period that will be studied for a long time, because it was such a pivotal era in our nation’s history. A new generation took up leadership of the country at the beginning of the decade, but at that optimistic moment few could have imagined the social and political chaos that would rain down by the end of the decade.

Many of the events and trends in the 1960s are well known and thoroughly studied, and they are also well outside the scope of this article. However, other events and trends in the 1960s remain largely unknown, and these are particularly relevant to investors in the financial markets today.

One such relevant series of events was the role the Federal Reserve played in initiating the Great Inflation, a trend which eventually led to real, inflation-adjusted losses in the financial markets that exceeded the real losses during the Great Depression.

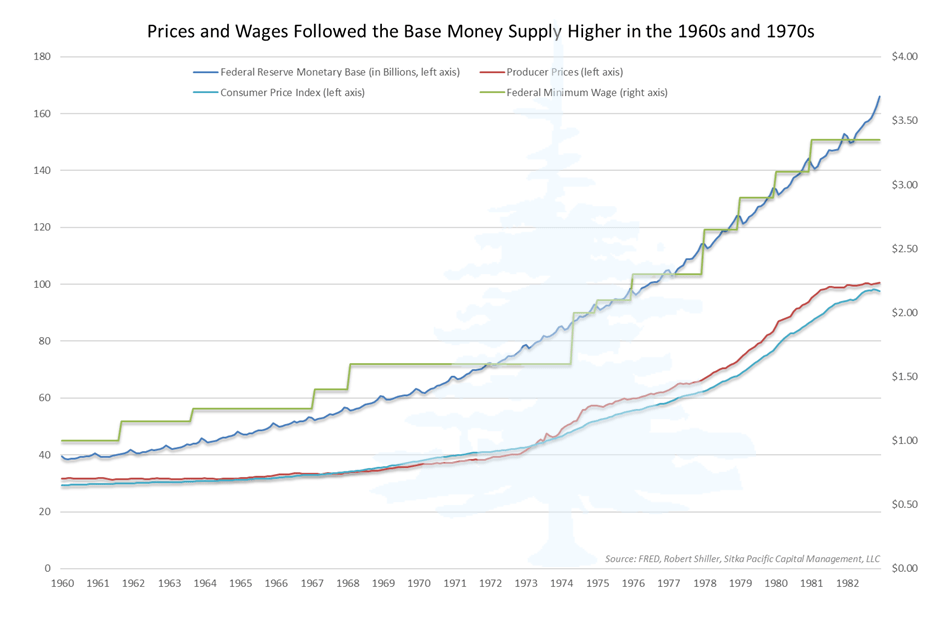

The Great Inflation refers to the years between the mid-1960s and the 1980s, during which time prices throughout the economy more than tripled. The Consumer Price Index, which represents only one attempt among many to track prices throughout the economy, rose from a value of 31 in 1964 all the way up to 100 in 1983. Prices continued to rise after 1983, but the period between 1964 and 1983 represents, by far, the largest and fastest rise in consumer prices in all of U.S. history.

Among Fed historians, the Great Inflation is also considered to be the second major policy error in the history of the Federal Reserve; the first major error being the decisions made in the early years of the Great Depression.

The rise in prices between the 1960s and the 1980s was not the result of an unpredictable series of random events, nor was it the result of many of the convenient scapegoats that were blamed at the time: greedy corporations and overbearing unions causing “cost-push” inflation, or an out of control “inflationary psychology” infesting the country. It also was not the result, at least directly, of the war in Vietnam, or of all the Great Society programs enacted by the Johnson administration. Prices have risen during every major war in U.S. history, as the sudden surge in government borrowing and spending during wartime inevitably results in scarcity.

Yet the rise in prices which began in the 1960s was different: prices began to rise with the increase in war spending, but instead of falling back when the wartime spending wound down, prices accelerated higher into the 1980s. Long after our involvement in Vietnam came to an end, prices continued higher, and long after the Great Inflation came to an end, the Great Society programs remained. While the war and increased spending on social programs were certainly factors, the root cause of the Great Inflation ran deeper.

At the time, there were many issues and parties that were blamed for rising prices, but the Great Inflation began, and was sustained, by the same force that has propelled all major inflations throughout history: it was a monetary phenomenon.

The Great Inflation happened because the policies of the Federal Reserve in the 1960s and 1970s not only enabled it to happen, they fostered it, and it ended precisely when the Fed decided to change those inflationary policies. Although we can never know how history would have unfolded if the Fed had changed course earlier, or had pursued another course from the beginning, it remains almost certain that the Great Inflation would not have happened had the Fed not pursued an overly expansionary monetary policy beginning in 1965.

* * *

Pivotal events in history, events which come to affect millions, sometimes turn on the decisions and personalities of only a few people. In the case of the Great Inflation, the chairman of the Federal Reserve was one of those few people. Among all those who have led the Federal Reserve in the century since its founding in 1913, the longest tenure has been that of William McChesney Martin Jr., who served as chairman of the Fed from 1951 to 1970.

Martin came of age, professionally, in the wake the Great Depression. His his father, William McChesney Martin Sr., had been a Fed governor and was one of the authors of the legislation which created the Federal Reserve system in 1913.

Martin Jr. was a banker by trade, and a close follower of the financial markets, and he began his career at the head of the Fed surrounded by other market-focused colleagues, before it came to be dominated by the best and the brightest later in the 1960s – i.e. those with economics PhDs. Thus, his early tenure at the Fed was defined by a pragmatic focus on financial market conditions, as can be expected from a banker, and he naturally trusted real-time statistics from the real world over economic models, theories and forecasts.

Martin was a consensus builder, and he tended to take in all sides of a debate and wait to make final decisions on policy until there was a clear majority in favor of one direction over another. He also had clear views regarding Fed independence.

Yet for someone looking back from the present time, those views were not as independent as you might think. He viewed the Fed as independent within the federal government, but not independent of the federal government. Although at first glance this may seem like a distinction without much of a difference, this subtlety would eventually prove to have enormous consequences for the country by the end of his time as chairman of the Fed.

In a May 1956 speech to a group of bankers in Pennsylvania, he summarized his views this way:

The Federal Reserve’s task of managing the money supply must be conducted with recognition of the Treasury’s requirements, for two reasons: one, the Federal Reserve has a duty to prevent financial panics, and a panic surely would follow if the Government, which represents the people as a whole, could not pay its bills; second, it would be the height of absurdity if the Federal Reserve were to say in effect that it didn’t think Congress was acting properly in authorizing expenditures, and therefore it wouldn’t help enable the Treasury to finance them.

In other words, he considered it to be Congress’ exclusive constitutional authority to determine the federal government’s levels of spending and taxation, and if Congress approved a budget that ran a deficit, the Federal Reserve was required to respect that constitutional authority and help finance it – or, at the very least, not pursue policies that made it difficult to finance the “the people’s” deficit.

This is quite different from how the Fed views its independence today. However, for a Fed chairman appointed in 1951, these views were not controversial. In 1961, the Fed had only just begun to recover some control over monetary policy after the takeover of monetary policy by the Treasury department during the 1940s. In the years that followed, the Fed remained in close communication and coordination with the Treasury throughout the Eisenhower administration, and that coordination continued during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations.

Thus, it was generally accepted at the time that one of the key roles of the Federal Reserve was to support the Treasury in meeting its financing requirements. On a more practical level, this most often meant it was the Fed’s responsibility to ensure the Treasury’s debt sales succeeded.

This was well before the time when the Treasury began auctioning its bills, notes and bonds in the 1970s – at this time, Treasury debt was mainly purchased directly by banks, at interest rates that were set ahead of time by the Treasury.

Since the Treasury generally wanted to sell debt at the lowest interest rate possible, and its buyers’ demand for additional debt hinged on the volume of excess reserves on hand in the banking system, reserves which were in large part influenced by the Fed’s reserve requirements, there was a constant underlying pressure on the Fed to 1) keep interest rates low, 2) keep interest rates steady, and 3) keep the banking system stocked with enough excess reserves to cover the Treasury’s anticipated debt sales when the government ran a deficit. All three of these pressures are inherently inflationary.

From the late 1930s and through the 1940s, this inherent tension between the Treasury’s desire to sell debt at terms as favorable as possible to the government and the Federal Reserve’s desire to maintain price stability did not end well for the Fed – it resulted in the takeover of monetary policy by the Treasury. This allowed the Treasury to sell all the debt it needed to finance the war at the terms it chose, and in the end this takeover had the predictably inflationary result: between 1939 and 1951, the Consumer Price Index rose at an average annual rate of 5.3%, and interest rates were far below the inflation rate. All told, during this short takeover of monetary policy by the federal government, consumer prices almost doubled, and cash lost almost half its purchasing power.

Following the war, the 1950s ushered in a new era of balanced government budgets. As a matter of principle, presidents Truman and Eisenhower both detested budget deficits, and although the Federal Budget fluctuated with the growth of the economy, the federal government’s debt barely changed between 1950 and 1960. This budgetary discipline throughout the 1950s more or less continued into the early 1960s, and it was no coincidence inflation rates during this period were low and steady. In the years between the time Martin became chairman of the Fed in 1951 through mid-1965, the Consumer Price Index rose only 20% – an average annual change of only 1.3%.

Yet shortly after Lyndon Johnson became president, the budgetary discipline which had reigned up to that point in Martin’s tenure as chairman of the Fed began to give way. While Truman, Eisenhower and Kennedy had all committed themselves to the goal of keeping the Federal budget reasonably balanced (as an example, Truman had insisted on raising taxes to finance the Korean war), Johnson and many of those in his administration wanted to increase Federal spending without risking an economic slowdown caused by raising taxes – a logic that sounds all too familiar to us today.

This shift in budgetary discipline did not appear out of nowhere – it came about from a new kind of philosophy within the economics community.

By the mid-1960s, many economists had come to accept the idea that the economy performed best when it was at “full employment,” and it could be kept closer to full employment if the government stepped in and played a role in maintaining adequate economic demand throughout the business cycle. In order to estimate the economy’s employment potential and the economy’s capacity for production and consumption, economists had developed models which not only tracked the economy’s current capacities for employment, production and consumption, but offered predictions of the economy’s future capacities. Thus, whenever employment was seen to be below the economy’s potential full employment, it was thought the government could boost the economy by increasing its spending, thereby creating enough economic demand to increase production and employment – and taxes. According to these models, the government could increase its spending when employment was below potential, and the additional spending would, almost like magic, “pay for itself” with the increased tax revenue that would come in from the spare economic capacity which had been put in motion.

Fed chairman Martin never did give much weight to economic models – his outlook was rooted in the empirical data coming in from financial markets and the banking system. However, as the 1960s progressed, he found himself increasingly surrounded by other appointed members of the Fed who did. In addition, the Johnson administration was full of officials who firmly believed in these new models, which offered a politically convenient theoretical justification for increasing government spending while not increasing taxes. In meetings within the Fed and with the president and various administration working groups, Martin found his views on the importance of non-inflationary growth increasingly outnumbered by those who viewed higher government spending and the resulting inflation as a way to get the economy to run closer to peak efficiency.

The year 1965 proved to be the year the growing conflict between Martin’s more conservative views and the views of the “new economists” of the 1960s came to a head.

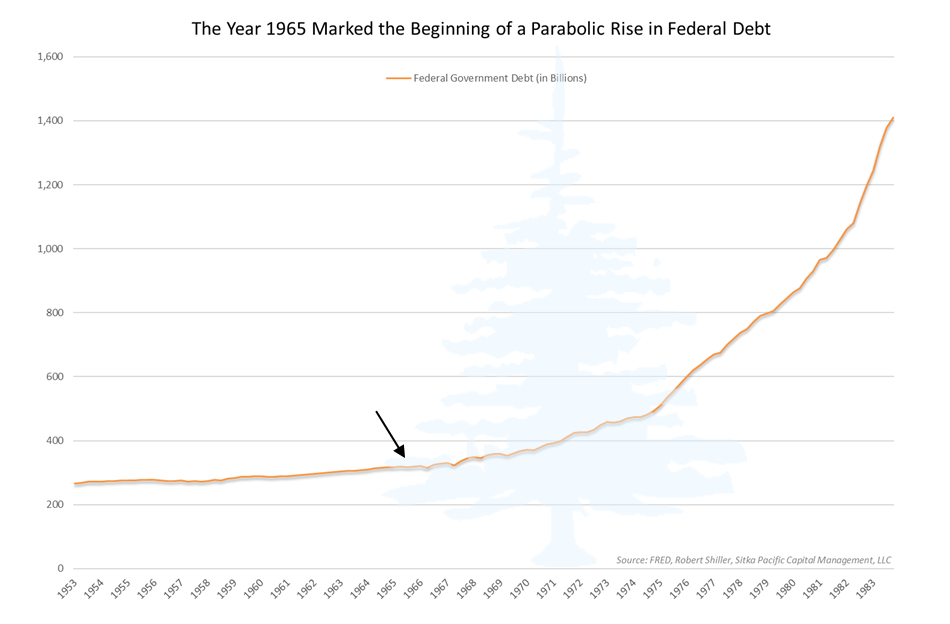

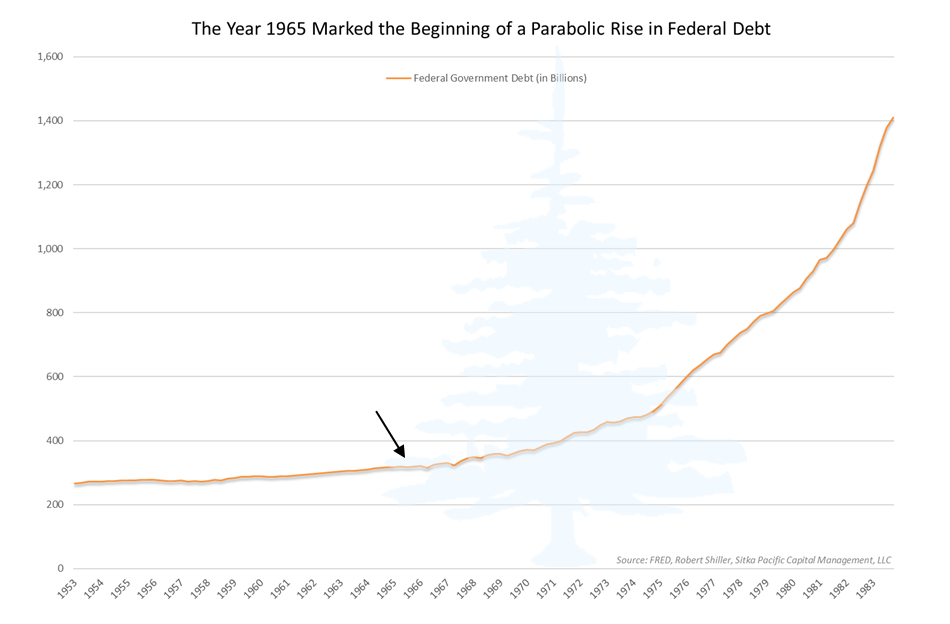

The year before, the president had signed a tax cut bill passed by Congress, and in 1965 spending for Johnson’s Great Society programs and the growing war in Vietnam began to increase dramatically. As a result, the government’s debt began to increase in a way it hadn’t done since the war: although the Federal debt had remained just below $300 billion from the end of World War II through 1962, it had climbed above that threshold to $320 billion by the end of 1965. Inflation had begun to increase as well. The Consumer Price Index had risen at a 1.2% annual rate in the first half of the decade, but by the end of 1965 the index had risen 1.9% from its level a year earlier, and looked poised to increase further. As it happens, this was the last time consumer prices would rise at less than a 2% annual rate for more than two decades.

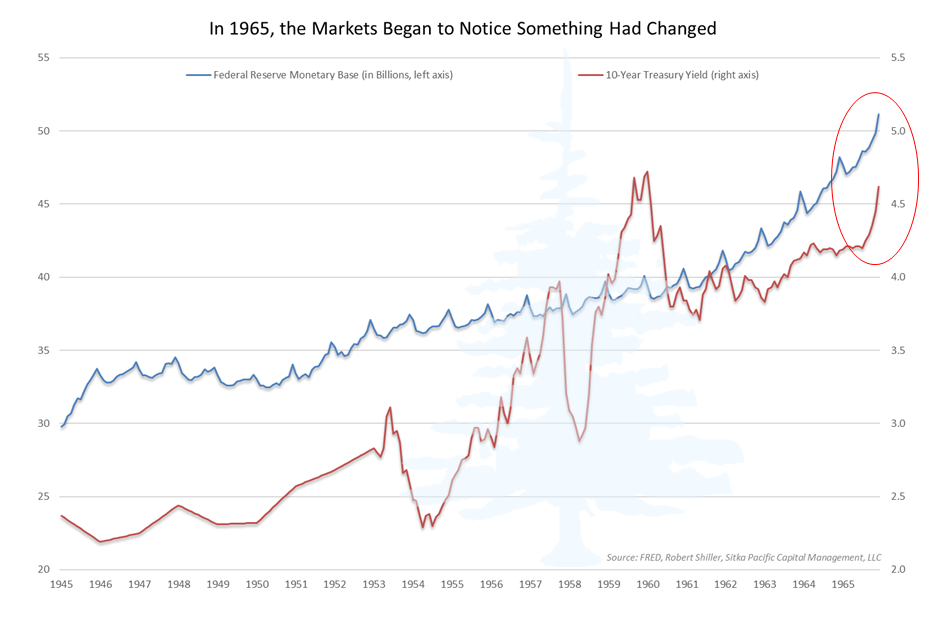

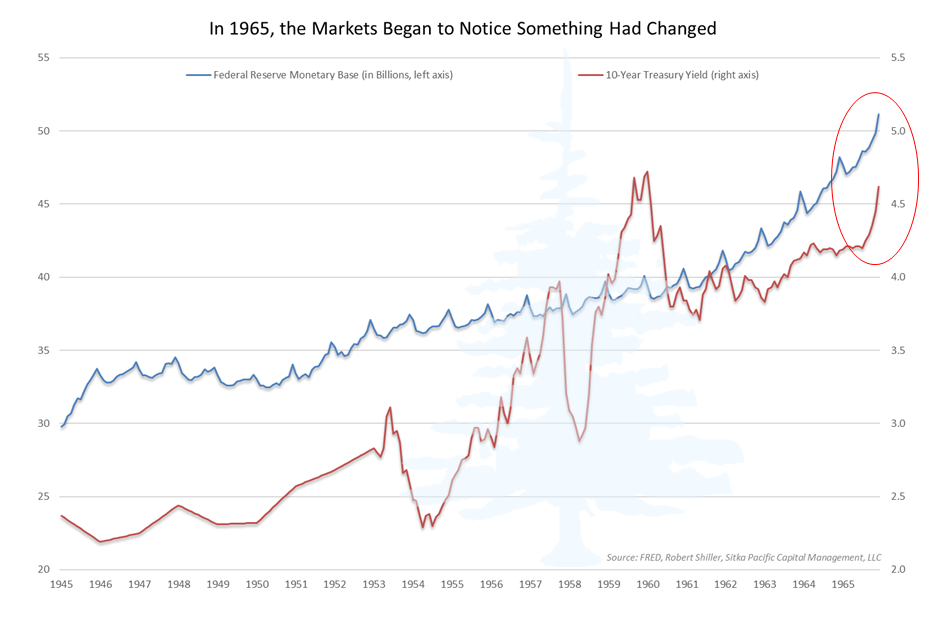

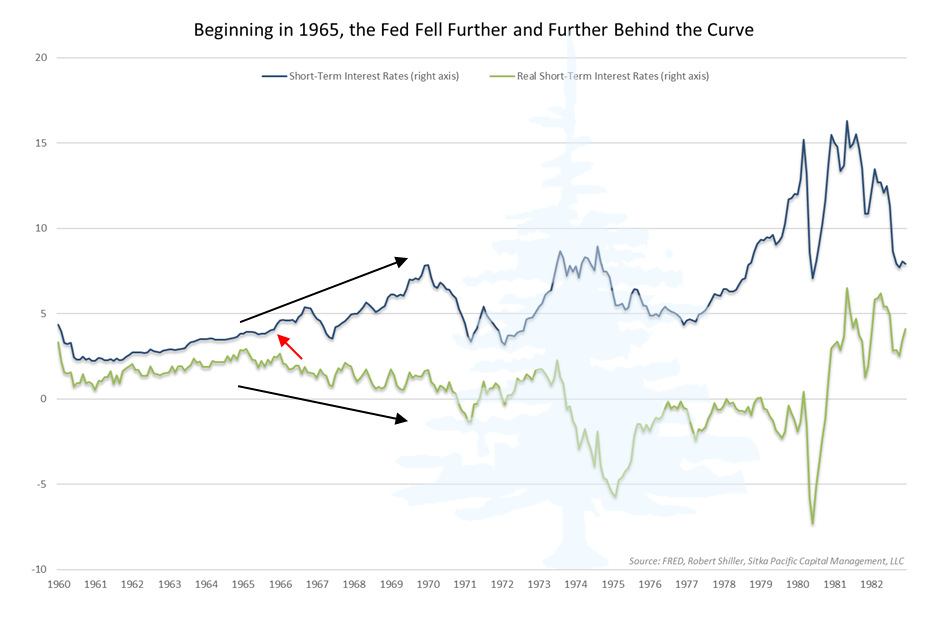

As they tend to do, financial markets quickly noticed something had changed, and began reacting: by the end of 1965, the yield on the 10-Year Treasury bond was rising quickly. It ended the year at 4.62%, up from 4.21% the year before, a rise that can be seen in the red line highlighted by the red circle below. Except for a brief moment at the dawn of the 1960s, this was the highest yield on the 10-Year Treasury since 1921.

At the same time as bond yields were rising, gold began to flow out of the U.S. at an alarming rate, as foreign central banks increasingly converted their accumulated dollars into gold. In all of 1965, $1.664 billion in gold left the U.S., which was about 10 times the amount that had left the year before. This was a strong signal that those outside the U.S. had also noticed U.S. fiscal and monetary policy had shifted in ways which would eventually put pressure on the value of the dollar, and they were taking action by exchanging more of their dollars for gold.

Martin and the other members of the Fed were aware something had changed, but they were conflicted about how the Fed should respond. Although the inflation rate of consumer prices remained benign prior to 1965, the growth rate of the base money supply had risen to a 5% annual rate in 1964, and by 1965 it was clear prices would probably begin to rise at a faster rate unless the Fed acted to slow money growth. Yet with the Fed Funds rate already at the high end of its historic range, a range that went back decades, raising the Fed Funds rate further seemed to most members of the Fed to be an extreme act that would invite a recession.

What Martin did not yet know was that the Johnson administration had begun hiding the official budget numbers from him and other members of the Fed, so they were unaware government spending was increasing much faster than they thought.

Part of the reason for the intentional hiding of this budget information was because Johnson apparently feared publicly telegraphing how much the U.S. was increasing its spending on the war in Vietnam, both for domestic political reasons and for fear the north Vietnamese would increase their war spending in response, if they knew about it. But it was also an effort to keep interest rates low.

In a memo in October 1965, Johnson’s budget director, Charles Schultz, wrote to the president:

“I have instructed my staff not to discuss the budgetary outlook with the Fed. Quite apart from security considerations I am afraid that the budgetary outlook would be used as an excuse to tighten up monetary policy.”

While governors of the Fed debated policy options in 1965, and while the Johnson administration withheld budget numbers and lobbied Martin in various inter-agency meetings to keep interest rates low, as the year wore on it became increasingly clear to Martin himself that the Fed needed to raise rates.

As the Fed maintained bank reserves at levels it viewed appropriate, the base money supply was growing at the highest rate since the Korean war, and other measures of credit were expanding rapidly. For data-dependent Martin, this mattered far more than the administration’s model-based projections for the federal budget, which showed the projected deficit in a more benign light (and which, unbeknownst to him, were partly based on intentionally misrepresented data). Then, in November, a government sale of short-term Treasury notes nearly failed. This was a clear indication that the market thought the interest rate offered on the notes was too low, and these were all signs to Martin that the Fed was quickly falling behind the curve.

Martin was also increasingly concerned the Fed had already sacrificed too much of its independence to the Johnson administration, and he was ready to increase rates, in part, to send a signal that the Fed was not going to be so swayed by political pressure, and was going to act according to its mandate for price stability.

So, when Johnson, who was recovering from surgery at the time at his Texas ranch, and had heard the Fed was about to raise interest rates, invited Martin and other officials to Texas in early December to discuss policy, Martin decided the Fed should increase interest rates before meeting the president. The Fed did so after meeting on December 3rd.

Martin then flew down to meet with Johnson on December 6th, which resulted in one of the most famous confrontations in Fed history. As Johnson physically pressed Martin up against the wall, he lambasted Martin for raising interest rates against his wishes. In the brief press conference that followed, Johnson emphasized that he and Martin had merely had a few differences of opinion on monetary policy, which would be worked out in due course. However, the look on Martin’s face betrayed the intensity of the meeting, which he only detailed years later.

Despite the intense pressure from Johnson and others in his administration, the Fed kept the December 1965 interest rate increase in place, and increased rates further in 1966. Among Fed historians, these acts are considered among the Fed’s proudest moments – Martin’s steadfast refusal to undo the December 1965 interest increase, despite being physically intimated by the president, stands as a symbolic act of the Fed’s independence.

Yet while Martin’s refusal to back down in the face of Johnson’s intimidation was certainly an honorable action, the fact was that pressure from the administration, on all fronts – through personal meetings with the president, and through working groups of Fed and administration officials – had already restrained monetary policy from where it probably would have been otherwise. In other words, the Fed was acting less independently than Martin’s refusal to back down would have it seem. The Fed was already behind the curve, and a big reason it was behind the curve had been due to pressure from the Johnson administration.

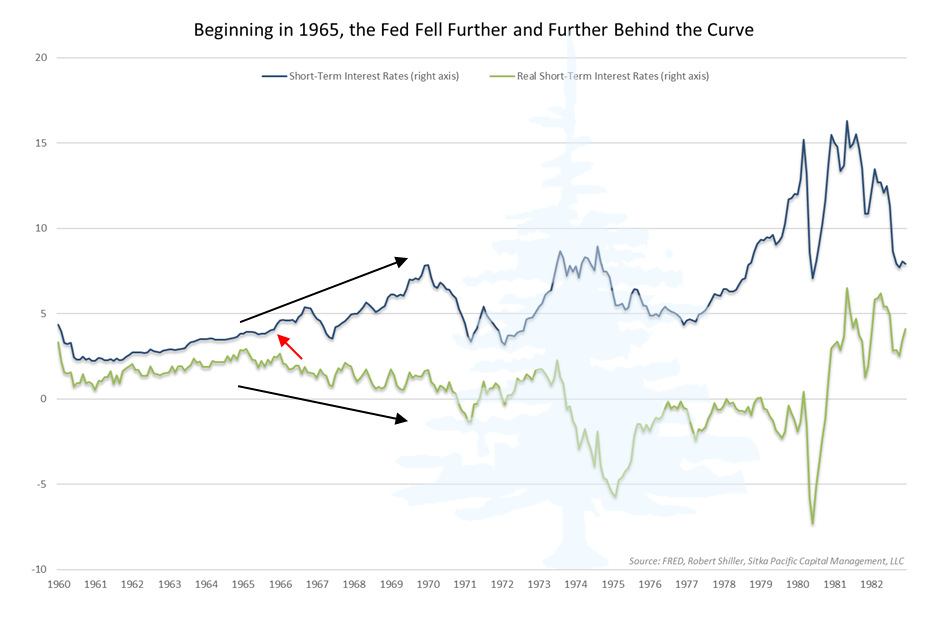

The infamous December 1965 rate hike is pointed at by the red arrow in the chart above. The blue line shows nominal short-term interest rates, and the Fed rate hike that December increased the 13-Week Treasury yield to 4.38% from 4.09% in November. With the exception of a brief spike to 4.49% in December 1959, this was the highest 13-Week Treasury yield in more than 35 years. This indicated to many officials at the Fed that monetary policy was relatively tight.

Yet as you can see by the green line in the chart above, while the nominal 13-Week Treasury yield was rising to new highs, the real, inflation-adjusted 13-Week Treasury yield was lower than it had been earlier in the year. This was because the inflation rate was rising faster than interest rates.

One source of many of the mistakes made during the Great Depression was that the Fed never looked at real, inflation-adjusted interest rates – it only considered nominal interest rates. So, when in 1931 interest rates fell to their lowest levels in decades, those within the Fed thought that monetary policy was the easiest it had been in decades. But at the time prices were falling at a 10% annual rate, and this meant that a 1% nominal interest rate was, in fact, an 11% real interest rate – which was very high. The Fed did not make the distinction between nominal and real interest rates in 1931, and as a result, the deflationary downward spiral that ensued came as a complete surprise.

Three decades later, in 1965, the Fed was still not looking at real interest rates, and as a result, the inflationary spiral that ensued also came as a complete surprise.

The diverging black arrows on the chart above highlight the pivot which occurred in 1965: although the Fed raised interest rates and brought them to higher and higher nominal levels with each subsequent economic expansion in the years that followed, real interest rates fell to lower and lower levels after 1965, as the Fed fell further and further behind the curve.

As real interest rates fell toward and then below zero, and the Fed’s monetary base continued to accelerate higher, the Great Inflation began.

* * *

The events in the years that followed the pivot in 1965 are some of the most significant moments in U.S. history, from a monetary perspective. The gold flow out of the U.S., which had dramatically increased in 1965, continued as foreign central banks increasingly converted their dollar reserves into gold in the face of the Fed’s increasingly expansionary policies. By 1970, the governments of all the major continental European economies had increased their gold holdings, particularly France. By 1971, the U.S. gold reserve had fallen to just over 8 metric tons, which was less than half of its size a decade earlier.

The gold redemptions continued until President Nixon decided to end dollar convertibility into gold in August 1971, effectively bringing the post-war Bretton Woods era to a close. This act also ended the idea that the U.S. dollar would be backed by a fixed amount of gold, or any other hard assets, redeemable at a specific price. This had been the foundation of currency in the U.S. since the aftermath of the Civil War.

In the early 1970s, both the new Fed chairman Arthur Burns and the Nixon administration traveled further down the inflationary road. They both favored monetary expansion over policies that would have slowed inflation, because they both had concluded that slowing inflation would require unacceptable rises in unemployment. Of course, “unacceptable” was meant in a purely political sense. Nixon had lost the presidential election in 1960, he firmly believed, because unemployment had risen just prior to voting time – so he relentlessly pushed policies that would counter any potential rise in unemployment.

Nixon also had a simpler and more pragmatic view of Federal Reserve independence than his predecessors. When Nixon installed Burns as chairman of the Fed in 1970, he said:

“I respect his independence. However, I hope that independently he will conclude that my views are the ones he should follow.”

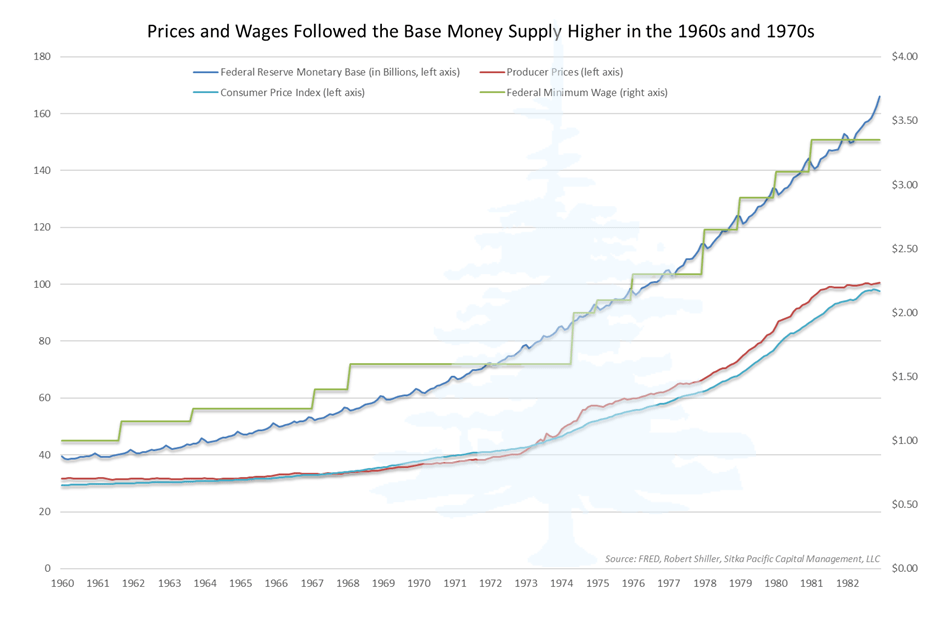

During this era, an unacceptable unemployment rate was considered anything over 4% – what the economic models of the time said was the full employment rate. In the relentless drive to keep the economy near full employment, the Fed ended monetary tightening campaigns and reverted to expansionary policies whenever unemployment rose above this rate, and this approach accelerated the inflation of prices through the 1970s (shown below).

At the same time, throughout the decade Chairman Burns blamed every conceivable cause for inflation except monetary growth, and in fact repeatedly made the claim in front of Congress that monetary policy could not slow inflation. It was only late in the 1970s, with inflation rates above 10% per year, that the goal of a 4% full employment rate was questioned, and the focus finally turned to slowing the growth of the money supply as the way to slow the rise in prices. In 1979, a year after having left the Fed, and with consumer prices having doubled over the previous decade, Burns finally conceded the following:

“Viewed in the abstract, the Federal Reserve System had the power to abort the inflation at its incipient stage fifteen years ago [in 1964] or at any other point, and it has the power to end it today [in 1979]. At any time in that period, it could have restricted the money supply and created sufficient strains in financial and industrial markets to terminate inflation with little delay. It did not do so because the Federal Reserve was itself caught up in the philosophical and political currents that were transforming American life and culture.”

In other words, had the Federal Reserve not been so swayed by the political interests of the then current presidents, and not so willing to follow the incredible idea that monetary expansion and higher inflation was a cost-free way to keep the economy running near peak efficiency, the Great Inflation would not have happened.

By the time it was stopped, consumer prices had tripled, the federal government’s debt had climbed past the $1 trillion mark, and financial markets had suffered the largest loss of real value since the Great Depression.

* * *

With such a large-scale and dramatic event such as the Great Inflation, there is no one person or one cause that explains everything that happened. In addition, there were many other factors which had a direct and significant impact on the rising trend in prices.

For example, if the same people in leadership positions at the Fed and the federal government had made the exact same decisions within the context of a stable or shrinking working population, instead of during the era which saw the emergence of the baby boom generation into the workforce, then prices would certainly have not risen as much as they did in the 1970s. Context always matters, and the demographics of the 1970s certainly favored an inflationary response to the increasing money supply.

Yet Arthur Burns was correct in 1979 that the Fed could have prevented inflation in the 1960s and 1970s, had it chosen to do so. It did not because the short-term costs – economic, social and political – seemed too much to bear. It was only when the short-term costs of not acting to slow inflation became unbearable that the Fed, under chairman Paul Volker, ended the Great Inflation by allowing real interest rates to rise back into positive territory.

The main reason understanding the Great Inflation is important is because the Federal Reserve is currently trapped in a monetary catch-22 very similar to where it was in the 1960s and 1970s.

While the implications of this have already had a profound effect on trends in the financial markets over the last 15 years, most of the impact of this trap is probably still ahead of us. Although some circumstances are clearly different today, and these differences have already had, and will continue to have, a great impact on how this period unfolds, the fundamental nature of this monetary trap is the same: the Fed is unable to maintain interest rates where they should be in order to maintain the value of the dollar over time, because the short-term costs – economic, social and political – seem too much to bear.

* * *

The preceding was part of our 2019 annual letter to clients, which they received in January 2019. To request a copy of the full letter, or to request a complimentary consultation to review your investments, visit Getting Started.

The content of this article is provided as general information and is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment or other advice. This material is not to be construed as a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any security, financial product, instrument or to participate in any particular trading strategy. Not all securities, products or services described are available in all countries, and nothing herein constitutes an offer or solicitation of any securities, products or services in any jurisdiction where their offer or sale is not qualified or exempt from registration or otherwise legally permissible.

Although the material herein is based upon information considered reliable and up-to-date, Sitka Pacific Capital Management, LLC does not assure that this material is accurate, current, or complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. Content in this document may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted, in whole or in part, without prior written consent — which is usually gladly given, as long as its use includes clear and proper attribution. Contact us for more information.

© Sitka Pacific Capital Management, LLC

The 1965 Pivot and a Rhyme of History

You went ahead and did something that you knew I disapproved of, that can affect my entire term here. You took advantage of me and I’m not going to forget it…You’ve got me into a position where you can run a rapier into me and you’ve run it.

Martin, my boys are dying in Vietnam, and you won’t print the money I need.

– President Lyndon Johnson to Fed Chairman William McChesney Martin, December 6, 1965

William McChesney Martin and Lyndon Johnson outside Johnson’s Texas ranch.

The study of history can be a surreal experience. Any look back at past events comes with the knowledge of many things which did or did not unfold afterwards, and this inevitably puts the events into a dreamlike context when they are looked at long after they happened. Some decisions and actions look prophetic, while others appear predictably tragic. Still others look much more intentional than they really were.

It is easy to make judgements from a safe perch in the future, which comes only after we know how things turned out. Yet it is not so easy to imagine what it would have been like to live through some period in history without knowing how the future would unfold. But it is a great challenge. Suspending any judgement stemming from our privileged place in the future while looking at history must be an exercise in vigilance and perseverance, if we are to distill the lessons relevant to our present time. Otherwise, we will fail to appreciate just how and why decisions are made, and how we can do better in the future.

The 1960s is a period that will be studied for a long time, because it was such a pivotal era in our nation’s history. A new generation took up leadership of the country at the beginning of the decade, but at that optimistic moment few could have imagined the social and political chaos that would rain down by the end of the decade.

Many of the events and trends in the 1960s are well known and thoroughly studied, and they are also well outside the scope of this article. However, other events and trends in the 1960s remain largely unknown, and these are particularly relevant to investors in the financial markets today.

One such relevant series of events was the role the Federal Reserve played in initiating the Great Inflation, a trend which eventually led to real, inflation-adjusted losses in the financial markets that exceeded the real losses during the Great Depression.

The Great Inflation refers to the years between the mid-1960s and the 1980s, during which time prices throughout the economy more than tripled. The Consumer Price Index, which represents only one attempt among many to track prices throughout the economy, rose from a value of 31 in 1964 all the way up to 100 in 1983. Prices continued to rise after 1983, but the period between 1964 and 1983 represents, by far, the largest and fastest rise in consumer prices in all of U.S. history.

Among Fed historians, the Great Inflation is also considered to be the second major policy error in the history of the Federal Reserve; the first major error being the decisions made in the early years of the Great Depression.

The rise in prices between the 1960s and the 1980s was not the result of an unpredictable series of random events, nor was it the result of many of the convenient scapegoats that were blamed at the time: greedy corporations and overbearing unions causing “cost-push” inflation, or an out of control “inflationary psychology” infesting the country. It also was not the result, at least directly, of the war in Vietnam, or of all the Great Society programs enacted by the Johnson administration. Prices have risen during every major war in U.S. history, as the sudden surge in government borrowing and spending during wartime inevitably results in scarcity.

Yet the rise in prices which began in the 1960s was different: prices began to rise with the increase in war spending, but instead of falling back when the wartime spending wound down, prices accelerated higher into the 1980s. Long after our involvement in Vietnam came to an end, prices continued higher, and long after the Great Inflation came to an end, the Great Society programs remained. While the war and increased spending on social programs were certainly factors, the root cause of the Great Inflation ran deeper.

At the time, there were many issues and parties that were blamed for rising prices, but the Great Inflation began, and was sustained, by the same force that has propelled all major inflations throughout history: it was a monetary phenomenon.

The Great Inflation happened because the policies of the Federal Reserve in the 1960s and 1970s not only enabled it to happen, they fostered it, and it ended precisely when the Fed decided to change those inflationary policies. Although we can never know how history would have unfolded if the Fed had changed course earlier, or had pursued another course from the beginning, it remains almost certain that the Great Inflation would not have happened had the Fed not pursued an overly expansionary monetary policy beginning in 1965.

* * *

Pivotal events in history, events which come to affect millions, sometimes turn on the decisions and personalities of only a few people. In the case of the Great Inflation, the chairman of the Federal Reserve was one of those few people. Among all those who have led the Federal Reserve in the century since its founding in 1913, the longest tenure has been that of William McChesney Martin Jr., who served as chairman of the Fed from 1951 to 1970.

Martin came of age, professionally, in the wake the Great Depression. His his father, William McChesney Martin Sr., had been a Fed governor and was one of the authors of the legislation which created the Federal Reserve system in 1913.

Martin Jr. was a banker by trade, and a close follower of the financial markets, and he began his career at the head of the Fed surrounded by other market-focused colleagues, before it came to be dominated by the best and the brightest later in the 1960s – i.e. those with economics PhDs. Thus, his early tenure at the Fed was defined by a pragmatic focus on financial market conditions, as can be expected from a banker, and he naturally trusted real-time statistics from the real world over economic models, theories and forecasts.

Martin was a consensus builder, and he tended to take in all sides of a debate and wait to make final decisions on policy until there was a clear majority in favor of one direction over another. He also had clear views regarding Fed independence.

Yet for someone looking back from the present time, those views were not as independent as you might think. He viewed the Fed as independent within the federal government, but not independent of the federal government. Although at first glance this may seem like a distinction without much of a difference, this subtlety would eventually prove to have enormous consequences for the country by the end of his time as chairman of the Fed.

In a May 1956 speech to a group of bankers in Pennsylvania, he summarized his views this way:

The Federal Reserve’s task of managing the money supply must be conducted with recognition of the Treasury’s requirements, for two reasons: one, the Federal Reserve has a duty to prevent financial panics, and a panic surely would follow if the Government, which represents the people as a whole, could not pay its bills; second, it would be the height of absurdity if the Federal Reserve were to say in effect that it didn’t think Congress was acting properly in authorizing expenditures, and therefore it wouldn’t help enable the Treasury to finance them.

In other words, he considered it to be Congress’ exclusive constitutional authority to determine the federal government’s levels of spending and taxation, and if Congress approved a budget that ran a deficit, the Federal Reserve was required to respect that constitutional authority and help finance it – or, at the very least, not pursue policies that made it difficult to finance the “the people’s” deficit.

This is quite different from how the Fed views its independence today. However, for a Fed chairman appointed in 1951, these views were not controversial. In 1961, the Fed had only just begun to recover some control over monetary policy after the takeover of monetary policy by the Treasury department during the 1940s. In the years that followed, the Fed remained in close communication and coordination with the Treasury throughout the Eisenhower administration, and that coordination continued during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations.

Thus, it was generally accepted at the time that one of the key roles of the Federal Reserve was to support the Treasury in meeting its financing requirements. On a more practical level, this most often meant it was the Fed’s responsibility to ensure the Treasury’s debt sales succeeded.

This was well before the time when the Treasury began auctioning its bills, notes and bonds in the 1970s – at this time, Treasury debt was mainly purchased directly by banks, at interest rates that were set ahead of time by the Treasury.

Since the Treasury generally wanted to sell debt at the lowest interest rate possible, and its buyers’ demand for additional debt hinged on the volume of excess reserves on hand in the banking system, reserves which were in large part influenced by the Fed’s reserve requirements, there was a constant underlying pressure on the Fed to 1) keep interest rates low, 2) keep interest rates steady, and 3) keep the banking system stocked with enough excess reserves to cover the Treasury’s anticipated debt sales when the government ran a deficit. All three of these pressures are inherently inflationary.

From the late 1930s and through the 1940s, this inherent tension between the Treasury’s desire to sell debt at terms as favorable as possible to the government and the Federal Reserve’s desire to maintain price stability did not end well for the Fed – it resulted in the takeover of monetary policy by the Treasury. This allowed the Treasury to sell all the debt it needed to finance the war at the terms it chose, and in the end this takeover had the predictably inflationary result: between 1939 and 1951, the Consumer Price Index rose at an average annual rate of 5.3%, and interest rates were far below the inflation rate. All told, during this short takeover of monetary policy by the federal government, consumer prices almost doubled, and cash lost almost half its purchasing power.

Following the war, the 1950s ushered in a new era of balanced government budgets. As a matter of principle, presidents Truman and Eisenhower both detested budget deficits, and although the Federal Budget fluctuated with the growth of the economy, the federal government’s debt barely changed between 1950 and 1960. This budgetary discipline throughout the 1950s more or less continued into the early 1960s, and it was no coincidence inflation rates during this period were low and steady. In the years between the time Martin became chairman of the Fed in 1951 through mid-1965, the Consumer Price Index rose only 20% – an average annual change of only 1.3%.

Yet shortly after Lyndon Johnson became president, the budgetary discipline which had reigned up to that point in Martin’s tenure as chairman of the Fed began to give way. While Truman, Eisenhower and Kennedy had all committed themselves to the goal of keeping the Federal budget reasonably balanced (as an example, Truman had insisted on raising taxes to finance the Korean war), Johnson and many of those in his administration wanted to increase Federal spending without risking an economic slowdown caused by raising taxes – a logic that sounds all too familiar to us today.

This shift in budgetary discipline did not appear out of nowhere – it came about from a new kind of philosophy within the economics community.

By the mid-1960s, many economists had come to accept the idea that the economy performed best when it was at “full employment,” and it could be kept closer to full employment if the government stepped in and played a role in maintaining adequate economic demand throughout the business cycle. In order to estimate the economy’s employment potential and the economy’s capacity for production and consumption, economists had developed models which not only tracked the economy’s current capacities for employment, production and consumption, but offered predictions of the economy’s future capacities. Thus, whenever employment was seen to be below the economy’s potential full employment, it was thought the government could boost the economy by increasing its spending, thereby creating enough economic demand to increase production and employment – and taxes. According to these models, the government could increase its spending when employment was below potential, and the additional spending would, almost like magic, “pay for itself” with the increased tax revenue that would come in from the spare economic capacity which had been put in motion.

Fed chairman Martin never did give much weight to economic models – his outlook was rooted in the empirical data coming in from financial markets and the banking system. However, as the 1960s progressed, he found himself increasingly surrounded by other appointed members of the Fed who did. In addition, the Johnson administration was full of officials who firmly believed in these new models, which offered a politically convenient theoretical justification for increasing government spending while not increasing taxes. In meetings within the Fed and with the president and various administration working groups, Martin found his views on the importance of non-inflationary growth increasingly outnumbered by those who viewed higher government spending and the resulting inflation as a way to get the economy to run closer to peak efficiency.

The year 1965 proved to be the year the growing conflict between Martin’s more conservative views and the views of the “new economists” of the 1960s came to a head.

The year before, the president had signed a tax cut bill passed by Congress, and in 1965 spending for Johnson’s Great Society programs and the growing war in Vietnam began to increase dramatically. As a result, the government’s debt began to increase in a way it hadn’t done since the war: although the Federal debt had remained just below $300 billion from the end of World War II through 1962, it had climbed above that threshold to $320 billion by the end of 1965. Inflation had begun to increase as well. The Consumer Price Index had risen at a 1.2% annual rate in the first half of the decade, but by the end of 1965 the index had risen 1.9% from its level a year earlier, and looked poised to increase further. As it happens, this was the last time consumer prices would rise at less than a 2% annual rate for more than two decades.

As they tend to do, financial markets quickly noticed something had changed, and began reacting: by the end of 1965, the yield on the 10-Year Treasury bond was rising quickly. It ended the year at 4.62%, up from 4.21% the year before, a rise that can be seen in the red line highlighted by the red circle below. Except for a brief moment at the dawn of the 1960s, this was the highest yield on the 10-Year Treasury since 1921.

At the same time as bond yields were rising, gold began to flow out of the U.S. at an alarming rate, as foreign central banks increasingly converted their accumulated dollars into gold. In all of 1965, $1.664 billion in gold left the U.S., which was about 10 times the amount that had left the year before. This was a strong signal that those outside the U.S. had also noticed U.S. fiscal and monetary policy had shifted in ways which would eventually put pressure on the value of the dollar, and they were taking action by exchanging more of their dollars for gold.

Martin and the other members of the Fed were aware something had changed, but they were conflicted about how the Fed should respond. Although the inflation rate of consumer prices remained benign prior to 1965, the growth rate of the base money supply had risen to a 5% annual rate in 1964, and by 1965 it was clear prices would probably begin to rise at a faster rate unless the Fed acted to slow money growth. Yet with the Fed Funds rate already at the high end of its historic range, a range that went back decades, raising the Fed Funds rate further seemed to most members of the Fed to be an extreme act that would invite a recession.

What Martin did not yet know was that the Johnson administration had begun hiding the official budget numbers from him and other members of the Fed, so they were unaware government spending was increasing much faster than they thought.

Part of the reason for the intentional hiding of this budget information was because Johnson apparently feared publicly telegraphing how much the U.S. was increasing its spending on the war in Vietnam, both for domestic political reasons and for fear the north Vietnamese would increase their war spending in response, if they knew about it. But it was also an effort to keep interest rates low.

In a memo in October 1965, Johnson’s budget director, Charles Schultz, wrote to the president:

“I have instructed my staff not to discuss the budgetary outlook with the Fed. Quite apart from security considerations I am afraid that the budgetary outlook would be used as an excuse to tighten up monetary policy.”

While governors of the Fed debated policy options in 1965, and while the Johnson administration withheld budget numbers and lobbied Martin in various inter-agency meetings to keep interest rates low, as the year wore on it became increasingly clear to Martin himself that the Fed needed to raise rates.

As the Fed maintained bank reserves at levels it viewed appropriate, the base money supply was growing at the highest rate since the Korean war, and other measures of credit were expanding rapidly. For data-dependent Martin, this mattered far more than the administration’s model-based projections for the federal budget, which showed the projected deficit in a more benign light (and which, unbeknownst to him, were partly based on intentionally misrepresented data). Then, in November, a government sale of short-term Treasury notes nearly failed. This was a clear indication that the market thought the interest rate offered on the notes was too low, and these were all signs to Martin that the Fed was quickly falling behind the curve.

Martin was also increasingly concerned the Fed had already sacrificed too much of its independence to the Johnson administration, and he was ready to increase rates, in part, to send a signal that the Fed was not going to be so swayed by political pressure, and was going to act according to its mandate for price stability.

So, when Johnson, who was recovering from surgery at the time at his Texas ranch, and had heard the Fed was about to raise interest rates, invited Martin and other officials to Texas in early December to discuss policy, Martin decided the Fed should increase interest rates before meeting the president. The Fed did so after meeting on December 3rd.

Martin then flew down to meet with Johnson on December 6th, which resulted in one of the most famous confrontations in Fed history. As Johnson physically pressed Martin up against the wall, he lambasted Martin for raising interest rates against his wishes. In the brief press conference that followed, Johnson emphasized that he and Martin had merely had a few differences of opinion on monetary policy, which would be worked out in due course. However, the look on Martin’s face betrayed the intensity of the meeting, which he only detailed years later.

Despite the intense pressure from Johnson and others in his administration, the Fed kept the December 1965 interest rate increase in place, and increased rates further in 1966. Among Fed historians, these acts are considered among the Fed’s proudest moments – Martin’s steadfast refusal to undo the December 1965 interest increase, despite being physically intimated by the president, stands as a symbolic act of the Fed’s independence.

Yet while Martin’s refusal to back down in the face of Johnson’s intimidation was certainly an honorable action, the fact was that pressure from the administration, on all fronts – through personal meetings with the president, and through working groups of Fed and administration officials – had already restrained monetary policy from where it probably would have been otherwise. In other words, the Fed was acting less independently than Martin’s refusal to back down would have it seem. The Fed was already behind the curve, and a big reason it was behind the curve had been due to pressure from the Johnson administration.

The infamous December 1965 rate hike is pointed at by the red arrow in the chart above. The blue line shows nominal short-term interest rates, and the Fed rate hike that December increased the 13-Week Treasury yield to 4.38% from 4.09% in November. With the exception of a brief spike to 4.49% in December 1959, this was the highest 13-Week Treasury yield in more than 35 years. This indicated to many officials at the Fed that monetary policy was relatively tight.

Yet as you can see by the green line in the chart above, while the nominal 13-Week Treasury yield was rising to new highs, the real, inflation-adjusted 13-Week Treasury yield was lower than it had been earlier in the year. This was because the inflation rate was rising faster than interest rates.

One source of many of the mistakes made during the Great Depression was that the Fed never looked at real, inflation-adjusted interest rates – it only considered nominal interest rates. So, when in 1931 interest rates fell to their lowest levels in decades, those within the Fed thought that monetary policy was the easiest it had been in decades. But at the time prices were falling at a 10% annual rate, and this meant that a 1% nominal interest rate was, in fact, an 11% real interest rate – which was very high. The Fed did not make the distinction between nominal and real interest rates in 1931, and as a result, the deflationary downward spiral that ensued came as a complete surprise.

Three decades later, in 1965, the Fed was still not looking at real interest rates, and as a result, the inflationary spiral that ensued also came as a complete surprise.

The diverging black arrows on the chart above highlight the pivot which occurred in 1965: although the Fed raised interest rates and brought them to higher and higher nominal levels with each subsequent economic expansion in the years that followed, real interest rates fell to lower and lower levels after 1965, as the Fed fell further and further behind the curve.

As real interest rates fell toward and then below zero, and the Fed’s monetary base continued to accelerate higher, the Great Inflation began.

* * *

The events in the years that followed the pivot in 1965 are some of the most significant moments in U.S. history, from a monetary perspective. The gold flow out of the U.S., which had dramatically increased in 1965, continued as foreign central banks increasingly converted their dollar reserves into gold in the face of the Fed’s increasingly expansionary policies. By 1970, the governments of all the major continental European economies had increased their gold holdings, particularly France. By 1971, the U.S. gold reserve had fallen to just over 8 metric tons, which was less than half of its size a decade earlier.

The gold redemptions continued until President Nixon decided to end dollar convertibility into gold in August 1971, effectively bringing the post-war Bretton Woods era to a close. This act also ended the idea that the U.S. dollar would be backed by a fixed amount of gold, or any other hard assets, redeemable at a specific price. This had been the foundation of currency in the U.S. since the aftermath of the Civil War.

In the early 1970s, both the new Fed chairman Arthur Burns and the Nixon administration traveled further down the inflationary road. They both favored monetary expansion over policies that would have slowed inflation, because they both had concluded that slowing inflation would require unacceptable rises in unemployment. Of course, “unacceptable” was meant in a purely political sense. Nixon had lost the presidential election in 1960, he firmly believed, because unemployment had risen just prior to voting time – so he relentlessly pushed policies that would counter any potential rise in unemployment.

Nixon also had a simpler and more pragmatic view of Federal Reserve independence than his predecessors. When Nixon installed Burns as chairman of the Fed in 1970, he said:

“I respect his independence. However, I hope that independently he will conclude that my views are the ones he should follow.”

During this era, an unacceptable unemployment rate was considered anything over 4% – what the economic models of the time said was the full employment rate. In the relentless drive to keep the economy near full employment, the Fed ended monetary tightening campaigns and reverted to expansionary policies whenever unemployment rose above this rate, and this approach accelerated the inflation of prices through the 1970s (shown below).

At the same time, throughout the decade Chairman Burns blamed every conceivable cause for inflation except monetary growth, and in fact repeatedly made the claim in front of Congress that monetary policy could not slow inflation. It was only late in the 1970s, with inflation rates above 10% per year, that the goal of a 4% full employment rate was questioned, and the focus finally turned to slowing the growth of the money supply as the way to slow the rise in prices. In 1979, a year after having left the Fed, and with consumer prices having doubled over the previous decade, Burns finally conceded the following:

“Viewed in the abstract, the Federal Reserve System had the power to abort the inflation at its incipient stage fifteen years ago [in 1964] or at any other point, and it has the power to end it today [in 1979]. At any time in that period, it could have restricted the money supply and created sufficient strains in financial and industrial markets to terminate inflation with little delay. It did not do so because the Federal Reserve was itself caught up in the philosophical and political currents that were transforming American life and culture.”

In other words, had the Federal Reserve not been so swayed by the political interests of the then current presidents, and not so willing to follow the incredible idea that monetary expansion and higher inflation was a cost-free way to keep the economy running near peak efficiency, the Great Inflation would not have happened.

By the time it was stopped, consumer prices had tripled, the federal government’s debt had climbed past the $1 trillion mark, and financial markets had suffered the largest loss of real value since the Great Depression.

* * *

With such a large-scale and dramatic event such as the Great Inflation, there is no one person or one cause that explains everything that happened. In addition, there were many other factors which had a direct and significant impact on the rising trend in prices.

For example, if the same people in leadership positions at the Fed and the federal government had made the exact same decisions within the context of a stable or shrinking working population, instead of during the era which saw the emergence of the baby boom generation into the workforce, then prices would certainly have not risen as much as they did in the 1970s. Context always matters, and the demographics of the 1970s certainly favored an inflationary response to the increasing money supply.

Yet Arthur Burns was correct in 1979 that the Fed could have prevented inflation in the 1960s and 1970s, had it chosen to do so. It did not because the short-term costs – economic, social and political – seemed too much to bear. It was only when the short-term costs of not acting to slow inflation became unbearable that the Fed, under chairman Paul Volker, ended the Great Inflation by allowing real interest rates to rise back into positive territory.

The main reason understanding the Great Inflation is important is because the Federal Reserve is currently trapped in a monetary catch-22 very similar to where it was in the 1960s and 1970s.

While the implications of this have already had a profound effect on trends in the financial markets over the last 15 years, most of the impact of this trap is probably still ahead of us. Although some circumstances are clearly different today, and these differences have already had, and will continue to have, a great impact on how this period unfolds, the fundamental nature of this monetary trap is the same: the Fed is unable to maintain interest rates where they should be in order to maintain the value of the dollar over time, because the short-term costs – economic, social and political – seem too much to bear.

* * *

The preceding was part of our 2019 annual letter to clients, which they received in January 2019. To request a copy of the full letter, or to request a complimentary consultation to review your investments, visit Getting Started.

The content of this article is provided as general information and is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment or other advice. This material is not to be construed as a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any security, financial product, instrument or to participate in any particular trading strategy. Not all securities, products or services described are available in all countries, and nothing herein constitutes an offer or solicitation of any securities, products or services in any jurisdiction where their offer or sale is not qualified or exempt from registration or otherwise legally permissible.

Although the material herein is based upon information considered reliable and up-to-date, Sitka Pacific Capital Management, LLC does not assure that this material is accurate, current, or complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. Content in this document may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted, in whole or in part, without prior written consent — which is usually gladly given, as long as its use includes clear and proper attribution. Contact us for more information.

© Sitka Pacific Capital Management, LLC

Investment Management

Before investing, we will discuss your goals and risk tolerances with you to see if a separately managed account at Sitka Pacific would be a good fit. To contact us for a free consultation, visit Getting Started.

Macro Value Monitor

To read a selection of recent client letters and be alerted when new letters are posted to our public site, visit Recent Client Letters.