A Brief Chronicle of the Federal Reserve’s First Balance Sheet Contraction

May 18, 2022

A top Federal Reserve official said the central bank is strongly committed to taking steps that will reduce inflation this year, including by approving significant reductions in its $9 trillion asset portfolio at its policy meeting early next month. Fed governor Lael Brainard, who is awaiting Senate confirmation to serve as the Fed’s vice chairwoman, said she anticipated shrinking the asset portfolio—sometimes referred to as a “balance sheet”—and a series of interest-rate increases to move the Fed’s policy stance to a more neutral position that no longer provides stimulus to the economy later this year.

“It is of paramount importance to get inflation down,” Ms. Brainard said Tuesday at a virtual conference hosted by the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. “Accordingly, the committee will continue tightening monetary policy methodically through a series of interest-rate increases and by starting to reduce the balance sheet at a rapid pace as soon as our May meeting.”

– The Wall Street Journal, April 5, 2022

If we follow the threads underlying inflation over the past year to their earliest beginnings, they run straight through the fog of pandemic, quickly pass by the financial crisis in 2008, and wind their way past the Great Inflation of the 1970s and the Fed-Treasury Accord twenty years before that, and stretch all the way back to the time when Captain Harry S. Truman, only recently returned from commanding an artillery battery during the Great War, opened Truman & Jacobson on the ground floor of the Glennon Hotel at 104 West 12th Street, in Kansas City, Missouri. It was late November, 1919.

From the moment it opened its doors, Truman & Jacobson reflected the dapper young man who would become president a quarter of a century later. The front entrance stood just below the name Truman & Jacobson in colored letters, and between two large glass windows, which displayed dozens of silk shirts and hats, along with scores of detachable collars arranged in vertical columns. Inside the doors, long glass display cases ran the length of the store and were filled with shirts, leather gloves and belts, socks, collar pins, and cufflinks. There was also a long row of hanging silk neckties in every color and pattern imaginable, which ran the length of the store on the left, behind the display cases. Behind the ties, boxes of shirts and everything else for sale in the store lined the walls.

To finance the remodeling of the space, the $350 monthly rent, and the $35,000 worth of inventory in its display cases and lining its walls, Harry had put in $15,000 of his own money. His partner Eddie Jacobson also contributed, but they also borrowed from the bank.

It was a first class operation, selling everything a gentleman in 1919 would need to look and feel top of the line. The entire 18-by-48-foot store gleamed. The tile floor was polished, the glass cases were kept spotless, and the new cash register, which bisected the display counter on the right, shined in the light emanating from the ceiling fans above. Next to one of the showcases stood a four-foot-high loving cup, a gift to “Captain Harry” from the soldiers of Artillery Battery D. And at the back of the store, the five flags of the allied nations hung on display.

As Harry and Eddie had hoped, Truman & Jacobson quickly became a local institution amid the bustling activity on 12th Street. The busy Muehlebach Hotel and the Dixon Hotel, both across the street, produced a steady stream of customers, and everyone seemed to be flush with money to spend.

The shop also became a rendezvous for war veterans, especially those Captain Harry had commanded in Artillery Battery D. “Twelfth Street was in its heyday and our war buddies and the Twelfth Street boys and girls were our customers,” Eddie would recall years later. “We all worked [downtown] and we all used to go up there once in a while at noontime. We’d walk around and go up there to Twelfth and Baltimore … and sometimes you’d see some of the fellows in there that would just come in to say hello …” former Battery D sergeant Frederick J. Bowman remembered. “I used to go there every time I was downtown,” said former corporal Harry Murphy. “It was sort of a headquarters. You went in there to find out what was going on…. [It] was a news center.”

They opened at 8 every morning and closed at 9pm, and business was brisk. In their first year, they racked up $70,000 in sales, and it looked as if they had firmly established themselves amid a booming post-war Kansas City. Yet unbeknownst to Harry and Eddie, the Board of Governors of the fledgling Federal Reserve had met a few weeks before they opened their doors, and had already made a decision that would prove fateful for Truman & Jacobson.

* * *

Just a few years into its existence as an institution, the Federal Reserve had been pressed into service to support massive government spending as the U.S. entered the Great War in Europe.

In the early years of the war, gold flowed into the U.S. as the European powers purchased war materiel from American companies and farms. This inflow of gold increased the domestic money supply, and prices began rising as a result. From a low inflation rate of 2% in 1915, inflation rose to an 11% rate in 1916. This increase in prices was fueled by an 11% rise in the base money supply in 1915, and a 15% increase in base money supply in 1916.

Because the rise in the U.S. money supply was due to an inflow of gold from abroad, the Federal Reserve remained powerless to mitigate the inflation of prices, since by the rules of the gold standard, the increase in gold automatically resulted in an increase the base money in the banking system.

After the U.S. officially entered the war in April 1917, however, the net inflow of gold from abroad slowed, but the base money supply continued to grow at a high rate as the Federal Reserve acted as an agent of the federal government. The Fed’s main function after April 1917 was to underwrite the sale of Treasury bonds and Liberty Loan drives — the two main vehicles of government borrowing during the war. In the two years between May 1917 and May 1919, there were four Liberty Loan drives and one Victory Loan drive, which came just after the war ended in early 1919.

Just before the U.S. entered the war, the federal government spent less than $1 billion on military expenditures, but spending rose to $15 billion a year by 1918 and 1919. In order to fund this massive increase in spending, tax rates were raised, but the bulk of the spending was financed with debt. Federal debt rose from $1.2 billion in 1916 to $25.5 billion in 1919, and the Federal Reserve expanded the money supply to facilitate the expansion. On top of the 11% rise in 2015 and the 15% increase in 2016, the base money supply rose 21% in 1917, and another 16% in 1918.

Although a number of Fed officials were uncomfortable with the Federal Reserve’s wartime role of financing the expansion of government debt by expanding the money supply, they had little choice. In May 1918, Congress passed the Departmental Reorganization Act, or the Overman Act as it was commonly known at the time, and this had given the president sweeping wartime powers to reorganize government agencies and direct private industry for the duration of the war, until six months after the war ended. Under this law, the Federal Reserve was directed by the Treasury Department in all manners of its operations, including how to sell Treasury bonds, and at what interest rates to sell the bonds, and also how to fund Liberty Loan drives. Had the Federal Reserve refused to carry out the instructions, the Treasury Department was authorized under the Overman Act to transfer the Fed’s authority over the money supply and the banking system to other agencies that would better serve the war effort.

By 1919, a total of $2 billion worth of gold had flowed into the U.S. from abroad during the war years, which brought the domestic gold supply to $4 billion, and the Federal Reserve had printed billions of dollars and lent this money to commercial banks, so they could purchase Liberty Loan bonds from the government and then sell them to the public. These sources — the gold inflow from abroad and the printing of money by the Fed — had expanded the base money supply in the U.S. by 250%. This, in turn, had fueled a 79% increase in prices throughout the U.S. economy.

Shortly after the war ended, the economy suffered a temporary downturn as war production wound down. However, as soldiers began returning home, and wartime price controls and rationing came to an end, consumers began shedding their wartime frugality — and a postwar boom commenced. Inflation, which had slowed with the brief economic downturn in early 1919, began to pick up in the summer, and by the autumn prices were again rising sharply as the economy entered a post-war boom.

The Federal Reserve, keenly aware of just how much the money supply had expanded during the war, met on November 3, 1919, to consider increasing interest rates to dampen accelerating inflation. A number of Fed governors, including the head of the New York branch of the Fed, Benjamin Strong, had argued at meetings earlier that summer and fall that an increase in interest rates was warranted.

However, the Treasury still held sway on interest rate decisions, and had opposed any rate increases that would affect the value of outstanding Treasury and Liberty Loan bonds. In July 1919, the Boston branch of the Federal Reserve requested permission to raise interest rates, but the Federal Reserve Board in Washington, D.C., rejected the request as “inadvisable from the point of view of the Treasury plans.” In September, the Treasury again insisted the Fed not increase interest rates, with Undersecretary of the Treasury Russell Leffingwell pointedly telling the board, “I ask that you do not increase your rates on paper secured by government obligations.” This objection to higher rates was repeated at the Federal Reserve Board’s meeting on October 28, on the grounds that higher rates would hurt the Treasury’s planned refinancing.

By the meeting on November 3, however, with inflation accelerating higher toward a 13% year-over-year rate, the Fed had had enough — and the Board voted to increase interest rates 0.25% to 4.25%. This was the first interest rate increase since the end of the war, and it sparked a seismic shift in the financial markets. Although the money supply and credit continued to expand, which continued to fuel prices higher throughout the economy, government bond yields began to rise and stock prices on the New York Stock Exchange began to fall. The amount of loans outstanding to brokers and dealers also began to decline, which indicated a reduced demand for “speculative” credit.

Although the Treasury Department had relented in its opposition to the 0.25% rate increase on November 3, it vehemently opposed further rate increases. At a meeting on November 19, the majority of Fed governors favored another rate increase, but Treasury Undersecretary Leffingwell convinced them a rate increase would be too harmful. Instead, Leffingwell urged the Fed to use “moral suasion” to convince commercial banks to curb new lending, at least until after the Treasury’s planned refinancing of debt in January. The Federal Reserve Board kept rates at 4.25%.

On November 24, however, the Federal Reserve Banks in Boston and New York voted on their own to increase the rates in their respective regions — and this prompted a ferocious attack from the Treasury. Leffingwell accused the head of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Benjamin Strong, of making “a direct attempt to punish the Treasury of the United States for not submitting to the dictation on the part of the Governor of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York even though it be at the cost of a shortage of funds of the Treasury to meet its outstanding obligations.” The Treasury, he said, was borrowing at a rate of $500 million a week until January 15, and he urged the Federal Reserve Board to disapprove the rate increases in New York and Boston — which it promptly did.

In response to being overridden, New York Fed Governor Strong met with Treasury Secretary Carter Glass and threatened to increase interest rates in New York without the Federal Reserve Board’s approval — claiming that Section 14 of the Federal Reserve Act of 1913 gave him sole authority over interest rates in his region. Incensed, the Treasury secretary threatened to have the president remove Strong and asked the attorney general to provide an official interpretation over who had the power to determine interest rates — the regional Federal Reserve Banks, or the Federal Reserve Board in Washington, D.C.

On December 9, the attorney general responded that “the Federal Reserve Board has the right, under the powers conferred by the Federal Reserve Act, to determine what rates should be charged … by a Federal Reserve Bank.” This cemented the Federal Reserve Board in Washington, D.C., as the sole authority over interest rates in the U.S.

The same day the attorney general issued his momentous opinion, Treasury Undersecretary Leffingwell wrote a letter to Treasury Secretary Glass, in which he detailed how the Treasury’s financial situation had recently improved, and in light of that, he wrote: “I do not think that a moderate further increase in rates at the present time would have a disastrous effect upon the Treasury’s position.” The following day, Leffingwell communicated a similar message to the Federal Reserve Board, and in response, the Board immediately sent telegrams to all the regional Fed Banks informing them they could begin raising interest rates — which they did, by another 0.25%. On December 30, the New York Fed raised interest rates by another 0.25% to 4.75%, and the other regional banks followed.

In mid-January 1920, Undersecretary Leffingwell reversed course and began pushing the Federal Reserve to increase interest rates all the way to 6% — far higher than the 4.25% he had vehemently opposed just six weeks prior. His reasons were twofold. First, the Treasury was no longer actively selling bonds to the financial markets, and thus no longer faced the prospect of higher interest costs if interest rates were to rise. Second, the gold stockpile of the Federal Reserve and the Treasury had begun to decline, and the ratio of reserve gold to the amount of notes outstanding was becoming critical.

As inflation accelerated into 1920, holders of Federal Reserve banknotes suddenly realized the purchasing power of their money was rapidly declining — and began exchanging their paper notes for gold. At the time, any holder of a $20 Federal Reserve note could walk into the bank and ask to exchange it, with an additional sixty-seven cents, for a one-ounce gold coin, which the bank was obliged to supply. This exchange resulted in no net change in the bank’s balance sheet, as a $20 note was worth the same as a one-ounce gold coin, but it reduced the amount of gold in the banking system relative to the number of banknotes in existence.

By January, the reserve ratio of gold to banknotes throughout the Federal Reserve system had fallen to 42.7%, and several regional Federal Reserve banks had a reserve ratio below 40%. The gold outflow from the banking system accelerated as a wartime embargo on gold exports out of the U.S. expired, and gold began being repatriated back to Europe. The Fed responded by pooling the gold reserves among the various regional banks, but the risk of suspension — of having to suspend the exchange of gold for dollars — was high and rising as gold reserves fell; in fact, the risk of suspension in 1920 would be higher than at any other time in the next fifty years.

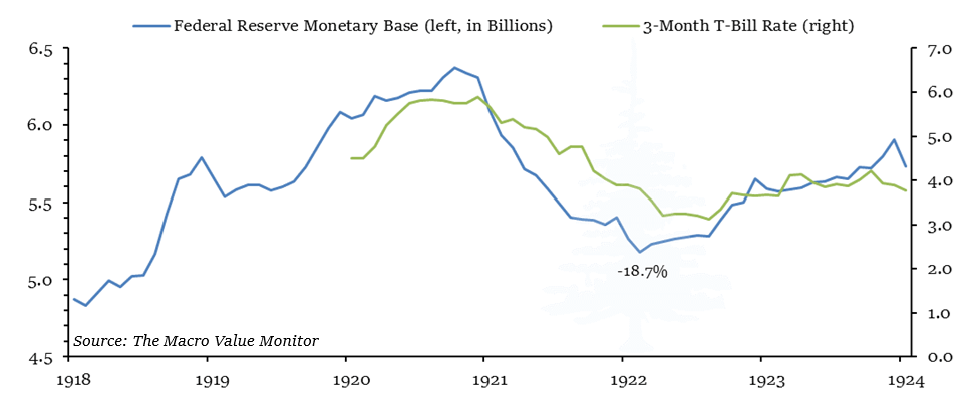

With the Treasury no longer in opposition, the Federal Reserve Board immediately began increasing interest rates. In February the Fed’s main policy rate was increased to 5%, and by June it had risen all the way to 7% — where it remained for the rest of the year. This increase was enough to stem the loss of gold from the banking system, but it also was enough to trigger a broad deflation of prices throughout the economy — and a severe contraction of credit.

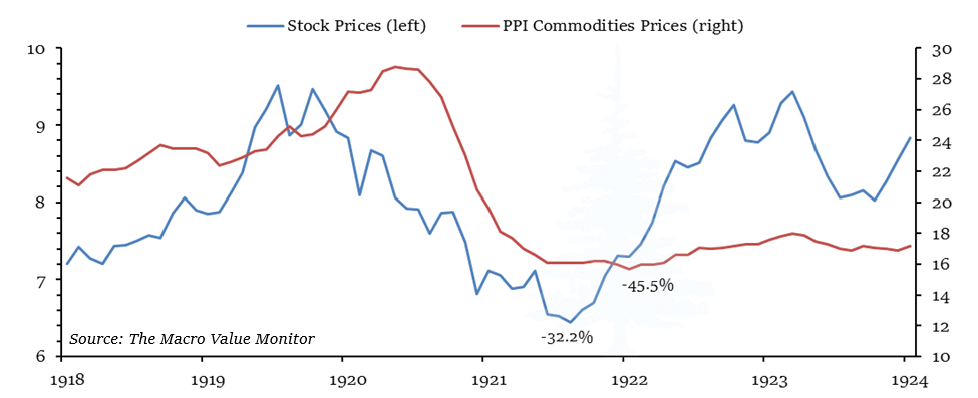

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) dates the end of the economic expansion after the Great War and the beginning of the subsequent depression to January 1920. Industrial production reached a peak that month, just a month after the Federal Reserve Board began increasing interest rates, and fell 23% over the following year. Unemployment rose from 4% in 1920 to 12% in 1921. Agricultural production fell 15% between 1920 and 1921, and commodity prices fell over 45% from their peak in the summer of 1920 to their trough in early 1922. Broader wholesale prices fell 37% between 1920 and 1921, a sharper decline than any year during the Great Depression a decade later.

As the contraction in economic output and prices took hold, however, the Federal Reserve maintained its main policy rate near 7%, and 3-Month Treasury bills traded at rates which would not be seen again until the late 1960s — at the beginning of the Great Inflation. Set against the backdrop of falling prices, this resulted in high real, inflation-adjusted interest rates, which reached 20.8% in June 1921. These high real rates were extremely deflationary, and the Federal Reserve, in its annual report in 1920, defended the deflationary monetary policy as necessary to unwind the inflation of prices during the war.

Benjamin Strong, governor of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, and by this time the de-facto leader of the Federal Reserve System, understood the costs of deflation — but advocated it anyway. In his assessment, the deflation of prices would be “accompanied by a considerable degree of unemployment, but not for very long, and that after a year or two of discomfort, embarrassment, some losses, some disorders caused by unemployment, we will emerge with an almost invincible banking position, prices more nearly at competitive levels with other nations, and be able to exercise a wide and important influence in restoring the world to a normal and livable condition.”

In downtown Kansas City, business at Truman & Jacobson began to dry up as commodity prices plummeted in late 1920. The price of wheat had been $2.12 a bushel in 1919, but by late 1920 it had fallen to $1.44 — a 32% drop. Agricultural prices overall fell 40%, and as farmers’ income and spending declined, so did the income and spending of nearly everyone else in the Midwest. By early 1921, the silk ties, shirts, leather gloves, belts, socks, collar pins and cufflinks that were flying out of the store in late 1919 and early 1920 remained on the shelves and on their hangers. Although many of the same people came through the store as had in 1919, including many veterans of Artillery Battery D, few were buying anything.

Harry and Eddie began borrowing money in 1921 to keep up with their mounting bills, but the economic contraction and deflation of prices continued. As former Battery D sergeant Frederick J. Bowman recalled, “A lot of the fellows that could have bought something would say, ‘Well, I need a couple of shirts, but I think I’ll wear these a while longer,’ because they just didn’t have the money to buy any.”

The store closed in 1922, and in September held a going-out-of-business sale. As Harry remembered decades later, “A flourishing business was carried on for about a year and a half and then came the squeeze of 1921. Jacobson and I went to bed one night with a $35,000 inventory and awoke the next day with a $25,000 shrinkage…. This brought bills payable and bank notes due at such a rapid rate we went out of business.“

Gross national product in the U.S. fell an estimated 8.4% from its January 2020 peak to its trough in 1922, and by that time the Federal Reserve’s base money supply had declined over 18% as economic activity and trade contracted. With agricultural prices almost half of their level two years earlier, and unemployment at 12%, the Midwest and other parts of the country were mired in depression. While Governor Strong and other Federal Reserve officials saw the deflation of the money supply and prices as a necessary unwinding of the inflation during the Great War, public attitudes had grown hostile.

At a meeting with the American Farm Bureau Federation in 1921, the group told Fed officials that “farmers feel that they have no financial system designed to meet their needs.” One representative pointedly asked, “Who decided that deflation was necessary?” Strong replied that “no one could have stopped it, and no one could have started it. In our opinion, it was bound to come.” All countries had experienced inflation during the war, he said, and all countries must deflate.

* * *

A quarter of a century after the failure of Truman & Jacobson, President Truman considered how best to manage the economic transition after the Second Great War. His experience during the depression of 1920–1922 greatly influenced his outlook, and he was determined to avoid deflation at all costs.

Unlike in 1919, when the expiration of the Overman Act re-established Federal Reserve independence shortly after World War I, the Federal Reserve would not regain its independence until six years after World War II. By that time, in Truman’s judgement, the economy was beyond the risk of deflation. As the Federal Reserve maintained its wartime interest rate pegs for Treasury securities, prices rose 17.6% between 1946 and 1947, 9.5% between 1947 and 1948, and continued higher until, by 1951, consumer prices were 45% higher than they had been in 1945. Only then did the Federal Reserve regain its independence with the Treasury-Fed Accord of 1951.

* * *

The content of this article is provided as general information and is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment or other advice. This material is not to be construed as a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any security, financial product, instrument or to participate in any particular trading strategy. Not all securities, products or services described are available in all countries, and nothing herein constitutes an offer or solicitation of any securities, products or services in any jurisdiction where their offer or sale is not qualified or exempt from registration or otherwise legally permissible.

Although the material herein is based upon information considered reliable and up-to-date, Sitka Pacific Capital Management, LLC does not assure that this material is accurate, current, or complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. Content in this document may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted, in whole or in part, without prior written consent — which is usually gladly given, as long as its use includes clear and proper attribution. Contact us for more information.

© Sitka Pacific Capital Management, LLC

A Brief Chronicle of the Federal Reserve’s First Balance Sheet Contraction

May 18, 2022

A top Federal Reserve official said the central bank is strongly committed to taking steps that will reduce inflation this year, including by approving significant reductions in its $9 trillion asset portfolio at its policy meeting early next month. Fed governor Lael Brainard, who is awaiting Senate confirmation to serve as the Fed’s vice chairwoman, said she anticipated shrinking the asset portfolio—sometimes referred to as a “balance sheet”—and a series of interest-rate increases to move the Fed’s policy stance to a more neutral position that no longer provides stimulus to the economy later this year.

“It is of paramount importance to get inflation down,” Ms. Brainard said Tuesday at a virtual conference hosted by the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. “Accordingly, the committee will continue tightening monetary policy methodically through a series of interest-rate increases and by starting to reduce the balance sheet at a rapid pace as soon as our May meeting.”

– The Wall Street Journal, April 5, 2022

If we follow the threads underlying inflation over the past year to their earliest beginnings, they run straight through the fog of pandemic, quickly pass by the financial crisis in 2008, and wind their way past the Great Inflation of the 1970s and the Fed-Treasury Accord twenty years before that, and stretch all the way back to the time when Captain Harry S. Truman, only recently returned from commanding an artillery battery during the Great War, opened Truman & Jacobson on the ground floor of the Glennon Hotel at 104 West 12th Street, in Kansas City, Missouri. It was late November, 1919.

From the moment it opened its doors, Truman & Jacobson reflected the dapper young man who would become president a quarter of a century later. The front entrance stood just below the name Truman & Jacobson in colored letters, and between two large glass windows, which displayed dozens of silk shirts and hats, along with scores of detachable collars arranged in vertical columns. Inside the doors, long glass display cases ran the length of the store and were filled with shirts, leather gloves and belts, socks, collar pins, and cufflinks. There was also a long row of hanging silk neckties in every color and pattern imaginable, which ran the length of the store on the left, behind the display cases. Behind the ties, boxes of shirts and everything else for sale in the store lined the walls.

To finance the remodeling of the space, the $350 monthly rent, and the $35,000 worth of inventory in its display cases and lining its walls, Harry had put in $15,000 of his own money. His partner Eddie Jacobson also contributed, but they also borrowed from the bank.

It was a first class operation, selling everything a gentleman in 1919 would need to look and feel top of the line. The entire 18-by-48-foot store gleamed. The tile floor was polished, the glass cases were kept spotless, and the new cash register, which bisected the display counter on the right, shined in the light emanating from the ceiling fans above. Next to one of the showcases stood a four-foot-high loving cup, a gift to “Captain Harry” from the soldiers of Artillery Battery D. And at the back of the store, the five flags of the allied nations hung on display.

As Harry and Eddie had hoped, Truman & Jacobson quickly became a local institution amid the bustling activity on 12th Street. The busy Muehlebach Hotel and the Dixon Hotel, both across the street, produced a steady stream of customers, and everyone seemed to be flush with money to spend.

The shop also became a rendezvous for war veterans, especially those Captain Harry had commanded in Artillery Battery D. “Twelfth Street was in its heyday and our war buddies and the Twelfth Street boys and girls were our customers,” Eddie would recall years later. “We all worked [downtown] and we all used to go up there once in a while at noontime. We’d walk around and go up there to Twelfth and Baltimore … and sometimes you’d see some of the fellows in there that would just come in to say hello …” former Battery D sergeant Frederick J. Bowman remembered. “I used to go there every time I was downtown,” said former corporal Harry Murphy. “It was sort of a headquarters. You went in there to find out what was going on…. [It] was a news center.”

They opened at 8 every morning and closed at 9pm, and business was brisk. In their first year, they racked up $70,000 in sales, and it looked as if they had firmly established themselves amid a booming post-war Kansas City. Yet unbeknownst to Harry and Eddie, the Board of Governors of the fledgling Federal Reserve had met a few weeks before they opened their doors, and had already made a decision that would prove fateful for Truman & Jacobson.

* * *

Just a few years into its existence as an institution, the Federal Reserve had been pressed into service to support massive government spending as the U.S. entered the Great War in Europe.

In the early years of the war, gold flowed into the U.S. as the European powers purchased war materiel from American companies and farms. This inflow of gold increased the domestic money supply, and prices began rising as a result. From a low inflation rate of 2% in 1915, inflation rose to an 11% rate in 1916. This increase in prices was fueled by an 11% rise in the base money supply in 1915, and a 15% increase in base money supply in 1916.

Because the rise in the U.S. money supply was due to an inflow of gold from abroad, the Federal Reserve remained powerless to mitigate the inflation of prices, since by the rules of the gold standard, the increase in gold automatically resulted in an increase the base money in the banking system.

After the U.S. officially entered the war in April 1917, however, the net inflow of gold from abroad slowed, but the base money supply continued to grow at a high rate as the Federal Reserve acted as an agent of the federal government. The Fed’s main function after April 1917 was to underwrite the sale of Treasury bonds and Liberty Loan drives — the two main vehicles of government borrowing during the war. In the two years between May 1917 and May 1919, there were four Liberty Loan drives and one Victory Loan drive, which came just after the war ended in early 1919.

Just before the U.S. entered the war, the federal government spent less than $1 billion on military expenditures, but spending rose to $15 billion a year by 1918 and 1919. In order to fund this massive increase in spending, tax rates were raised, but the bulk of the spending was financed with debt. Federal debt rose from $1.2 billion in 1916 to $25.5 billion in 1919, and the Federal Reserve expanded the money supply to facilitate the expansion. On top of the 11% rise in 2015 and the 15% increase in 2016, the base money supply rose 21% in 1917, and another 16% in 1918.

Although a number of Fed officials were uncomfortable with the Federal Reserve’s wartime role of financing the expansion of government debt by expanding the money supply, they had little choice. In May 1918, Congress passed the Departmental Reorganization Act, or the Overman Act as it was commonly known at the time, and this had given the president sweeping wartime powers to reorganize government agencies and direct private industry for the duration of the war, until six months after the war ended. Under this law, the Federal Reserve was directed by the Treasury Department in all manners of its operations, including how to sell Treasury bonds, and at what interest rates to sell the bonds, and also how to fund Liberty Loan drives. Had the Federal Reserve refused to carry out the instructions, the Treasury Department was authorized under the Overman Act to transfer the Fed’s authority over the money supply and the banking system to other agencies that would better serve the war effort.

By 1919, a total of $2 billion worth of gold had flowed into the U.S. from abroad during the war years, which brought the domestic gold supply to $4 billion, and the Federal Reserve had printed billions of dollars and lent this money to commercial banks, so they could purchase Liberty Loan bonds from the government and then sell them to the public. These sources — the gold inflow from abroad and the printing of money by the Fed — had expanded the base money supply in the U.S. by 250%. This, in turn, had fueled a 79% increase in prices throughout the U.S. economy.

Shortly after the war ended, the economy suffered a temporary downturn as war production wound down. However, as soldiers began returning home, and wartime price controls and rationing came to an end, consumers began shedding their wartime frugality — and a postwar boom commenced. Inflation, which had slowed with the brief economic downturn in early 1919, began to pick up in the summer, and by the autumn prices were again rising sharply as the economy entered a post-war boom.

The Federal Reserve, keenly aware of just how much the money supply had expanded during the war, met on November 3, 1919, to consider increasing interest rates to dampen accelerating inflation. A number of Fed governors, including the head of the New York branch of the Fed, Benjamin Strong, had argued at meetings earlier that summer and fall that an increase in interest rates was warranted.

However, the Treasury still held sway on interest rate decisions, and had opposed any rate increases that would affect the value of outstanding Treasury and Liberty Loan bonds. In July 1919, the Boston branch of the Federal Reserve requested permission to raise interest rates, but the Federal Reserve Board in Washington, D.C., rejected the request as “inadvisable from the point of view of the Treasury plans.” In September, the Treasury again insisted the Fed not increase interest rates, with Undersecretary of the Treasury Russell Leffingwell pointedly telling the board, “I ask that you do not increase your rates on paper secured by government obligations.” This objection to higher rates was repeated at the Federal Reserve Board’s meeting on October 28, on the grounds that higher rates would hurt the Treasury’s planned refinancing.

By the meeting on November 3, however, with inflation accelerating higher toward a 13% year-over-year rate, the Fed had had enough — and the Board voted to increase interest rates 0.25% to 4.25%. This was the first interest rate increase since the end of the war, and it sparked a seismic shift in the financial markets. Although the money supply and credit continued to expand, which continued to fuel prices higher throughout the economy, government bond yields began to rise and stock prices on the New York Stock Exchange began to fall. The amount of loans outstanding to brokers and dealers also began to decline, which indicated a reduced demand for “speculative” credit.

Although the Treasury Department had relented in its opposition to the 0.25% rate increase on November 3, it vehemently opposed further rate increases. At a meeting on November 19, the majority of Fed governors favored another rate increase, but Treasury Undersecretary Leffingwell convinced them a rate increase would be too harmful. Instead, Leffingwell urged the Fed to use “moral suasion” to convince commercial banks to curb new lending, at least until after the Treasury’s planned refinancing of debt in January. The Federal Reserve Board kept rates at 4.25%.

On November 24, however, the Federal Reserve Banks in Boston and New York voted on their own to increase the rates in their respective regions — and this prompted a ferocious attack from the Treasury. Leffingwell accused the head of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Benjamin Strong, of making “a direct attempt to punish the Treasury of the United States for not submitting to the dictation on the part of the Governor of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York even though it be at the cost of a shortage of funds of the Treasury to meet its outstanding obligations.” The Treasury, he said, was borrowing at a rate of $500 million a week until January 15, and he urged the Federal Reserve Board to disapprove the rate increases in New York and Boston — which it promptly did.

In response to being overridden, New York Fed Governor Strong met with Treasury Secretary Carter Glass and threatened to increase interest rates in New York without the Federal Reserve Board’s approval — claiming that Section 14 of the Federal Reserve Act of 1913 gave him sole authority over interest rates in his region. Incensed, the Treasury secretary threatened to have the president remove Strong and asked the attorney general to provide an official interpretation over who had the power to determine interest rates — the regional Federal Reserve Banks, or the Federal Reserve Board in Washington, D.C.

On December 9, the attorney general responded that “the Federal Reserve Board has the right, under the powers conferred by the Federal Reserve Act, to determine what rates should be charged … by a Federal Reserve Bank.” This cemented the Federal Reserve Board in Washington, D.C., as the sole authority over interest rates in the U.S.

The same day the attorney general issued his momentous opinion, Treasury Undersecretary Leffingwell wrote a letter to Treasury Secretary Glass, in which he detailed how the Treasury’s financial situation had recently improved, and in light of that, he wrote: “I do not think that a moderate further increase in rates at the present time would have a disastrous effect upon the Treasury’s position.” The following day, Leffingwell communicated a similar message to the Federal Reserve Board, and in response, the Board immediately sent telegrams to all the regional Fed Banks informing them they could begin raising interest rates — which they did, by another 0.25%. On December 30, the New York Fed raised interest rates by another 0.25% to 4.75%, and the other regional banks followed.

In mid-January 1920, Undersecretary Leffingwell reversed course and began pushing the Federal Reserve to increase interest rates all the way to 6% — far higher than the 4.25% he had vehemently opposed just six weeks prior. His reasons were twofold. First, the Treasury was no longer actively selling bonds to the financial markets, and thus no longer faced the prospect of higher interest costs if interest rates were to rise. Second, the gold stockpile of the Federal Reserve and the Treasury had begun to decline, and the ratio of reserve gold to the amount of notes outstanding was becoming critical.

As inflation accelerated into 1920, holders of Federal Reserve banknotes suddenly realized the purchasing power of their money was rapidly declining — and began exchanging their paper notes for gold. At the time, any holder of a $20 Federal Reserve note could walk into the bank and ask to exchange it, with an additional sixty-seven cents, for a one-ounce gold coin, which the bank was obliged to supply. This exchange resulted in no net change in the bank’s balance sheet, as a $20 note was worth the same as a one-ounce gold coin, but it reduced the amount of gold in the banking system relative to the number of banknotes in existence.

By January, the reserve ratio of gold to banknotes throughout the Federal Reserve system had fallen to 42.7%, and several regional Federal Reserve banks had a reserve ratio below 40%. The gold outflow from the banking system accelerated as a wartime embargo on gold exports out of the U.S. expired, and gold began being repatriated back to Europe. The Fed responded by pooling the gold reserves among the various regional banks, but the risk of suspension — of having to suspend the exchange of gold for dollars — was high and rising as gold reserves fell; in fact, the risk of suspension in 1920 would be higher than at any other time in the next fifty years.

With the Treasury no longer in opposition, the Federal Reserve Board immediately began increasing interest rates. In February the Fed’s main policy rate was increased to 5%, and by June it had risen all the way to 7% — where it remained for the rest of the year. This increase was enough to stem the loss of gold from the banking system, but it also was enough to trigger a broad deflation of prices throughout the economy — and a severe contraction of credit.

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) dates the end of the economic expansion after the Great War and the beginning of the subsequent depression to January 1920. Industrial production reached a peak that month, just a month after the Federal Reserve Board began increasing interest rates, and fell 23% over the following year. Unemployment rose from 4% in 1920 to 12% in 1921. Agricultural production fell 15% between 1920 and 1921, and commodity prices fell over 45% from their peak in the summer of 1920 to their trough in early 1922. Broader wholesale prices fell 37% between 1920 and 1921, a sharper decline than any year during the Great Depression a decade later.

As the contraction in economic output and prices took hold, however, the Federal Reserve maintained its main policy rate near 7%, and 3-Month Treasury bills traded at rates which would not be seen again until the late 1960s — at the beginning of the Great Inflation. Set against the backdrop of falling prices, this resulted in high real, inflation-adjusted interest rates, which reached 20.8% in June 1921. These high real rates were extremely deflationary, and the Federal Reserve, in its annual report in 1920, defended the deflationary monetary policy as necessary to unwind the inflation of prices during the war.

Benjamin Strong, governor of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, and by this time the de-facto leader of the Federal Reserve System, understood the costs of deflation — but advocated it anyway. In his assessment, the deflation of prices would be “accompanied by a considerable degree of unemployment, but not for very long, and that after a year or two of discomfort, embarrassment, some losses, some disorders caused by unemployment, we will emerge with an almost invincible banking position, prices more nearly at competitive levels with other nations, and be able to exercise a wide and important influence in restoring the world to a normal and livable condition.”

In downtown Kansas City, business at Truman & Jacobson began to dry up as commodity prices plummeted in late 1920. The price of wheat had been $2.12 a bushel in 1919, but by late 1920 it had fallen to $1.44 — a 32% drop. Agricultural prices overall fell 40%, and as farmers’ income and spending declined, so did the income and spending of nearly everyone else in the Midwest. By early 1921, the silk ties, shirts, leather gloves, belts, socks, collar pins and cufflinks that were flying out of the store in late 1919 and early 1920 remained on the shelves and on their hangers. Although many of the same people came through the store as had in 1919, including many veterans of Artillery Battery D, few were buying anything.

Harry and Eddie began borrowing money in 1921 to keep up with their mounting bills, but the economic contraction and deflation of prices continued. As former Battery D sergeant Frederick J. Bowman recalled, “A lot of the fellows that could have bought something would say, ‘Well, I need a couple of shirts, but I think I’ll wear these a while longer,’ because they just didn’t have the money to buy any.”

The store closed in 1922, and in September held a going-out-of-business sale. As Harry remembered decades later, “A flourishing business was carried on for about a year and a half and then came the squeeze of 1921. Jacobson and I went to bed one night with a $35,000 inventory and awoke the next day with a $25,000 shrinkage…. This brought bills payable and bank notes due at such a rapid rate we went out of business.“

Gross national product in the U.S. fell an estimated 8.4% from its January 2020 peak to its trough in 1922, and by that time the Federal Reserve’s base money supply had declined over 18% as economic activity and trade contracted. With agricultural prices almost half of their level two years earlier, and unemployment at 12%, the Midwest and other parts of the country were mired in depression. While Governor Strong and other Federal Reserve officials saw the deflation of the money supply and prices as a necessary unwinding of the inflation during the Great War, public attitudes had grown hostile.

At a meeting with the American Farm Bureau Federation in 1921, the group told Fed officials that “farmers feel that they have no financial system designed to meet their needs.” One representative pointedly asked, “Who decided that deflation was necessary?” Strong replied that “no one could have stopped it, and no one could have started it. In our opinion, it was bound to come.” All countries had experienced inflation during the war, he said, and all countries must deflate.

* * *

A quarter of a century after the failure of Truman & Jacobson, President Truman considered how best to manage the economic transition after the Second Great War. His experience during the depression of 1920–1922 greatly influenced his outlook, and he was determined to avoid deflation at all costs.

Unlike in 1919, when the expiration of the Overman Act re-established Federal Reserve independence shortly after World War I, the Federal Reserve would not regain its independence until six years after World War II. By that time, in Truman’s judgement, the economy was beyond the risk of deflation. As the Federal Reserve maintained its wartime interest rate pegs for Treasury securities, prices rose 17.6% between 1946 and 1947, 9.5% between 1947 and 1948, and continued higher until, by 1951, consumer prices were 45% higher than they had been in 1945. Only then did the Federal Reserve regain its independence with the Treasury-Fed Accord of 1951.

* * *

The content of this article is provided as general information and is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment or other advice. This material is not to be construed as a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any security, financial product, instrument or to participate in any particular trading strategy. Not all securities, products or services described are available in all countries, and nothing herein constitutes an offer or solicitation of any securities, products or services in any jurisdiction where their offer or sale is not qualified or exempt from registration or otherwise legally permissible.

Although the material herein is based upon information considered reliable and up-to-date, Sitka Pacific Capital Management, LLC does not assure that this material is accurate, current, or complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. Content in this document may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted, in whole or in part, without prior written consent — which is usually gladly given, as long as its use includes clear and proper attribution. Contact us for more information.

© Sitka Pacific Capital Management, LLC

Investment Management

Before investing, we will discuss your goals and risk tolerances with you to see if a separately managed account at Sitka Pacific would be a good fit. To contact us for a free consultation, visit Getting Started.

Macro Value Monitor

To read a selection of recent client letters and be alerted when new letters are posted to our public site, visit Recent Client Letters.