How an Inflationary End to the Bountiful Triple Dip Swindled Equity Investors

August 10, 2022

The continuation of some degree of inflation is certainly probable in the future, and that is the chief reason why most intelligent investors now recognize that some common stocks must be included in their portfolio. However, that is only part of the question of the effect of inflation on investment policy…

[T]he argument that common stocks are and always will be attractive, including the present time, because of their excellent record since 1949 – involves in those terms a very fundamental and important fallacy. This is the idea that the better the past record of the stock market as such, the more certain it is that common stocks are sound investments for the future… But you cannot say that the fact that the stock market has risen continuously (or slightly irregularly) over a long period in the past is a guarantee that it will continue to act that way in the future. As I see it, the real truth is exactly the opposite, for the higher the stock market advances the more reason there is to mistrust its future action…

~ Benjamin Graham, November 15, 1963

‘How did you go bankrupt?’ Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.

~ From The Sun Also Rises, by Ernest Hemingway

The year 1963, not unlike the years we have experienced recently, was a period of growing turbulence in the United States. Both at home and abroad, seeds were being sown for social, political and economic changes that would come to define the era ahead, in ways few could then imagine. Yet at the time, those changes were still beyond the horizon, and for most of the country, and especially for those in the financial markets, 1963 seemed like it was the best of times.

The stock market was a potent symbol of that best of times feeling. Over the previous fourteen years, stocks had been rising almost without interruption, and the equity market had quadrupled since the dust had settled after the Second World War. Interest rates were comfortably low as 1963 began, as was inflation. Consumer prices had risen just 1.3% over the past year, and the rationing, price controls and inflation during and after the war were a distant memory. So was the debilitating unemployment of the Great Depression.

The torch had recently been passed to John F. Kennedy, and his cadre of the best and the brightest seemed to embody a new era of optimism. The prior summer Kennedy had announced the U.S. would land on the moon before the end of the decade, and the Mercury missions were already carrying Americans into space. And although the Cold War with the Soviet Union hung overhead, Kennedy had just convinced Khrushchev to remove the nuclear missiles that had been secretly installed in Cuba. By the end of 1962, having faced down the Soviet Union, and with the stock market fully recovering — yet again — from another selloff, it seemed Kennedy and the U.S. were poised to continue on a firm upward trajectory.

As 1963 began, however, events began to unfold that would prove to be harbingers of more difficult times to come.

On the second day of January, 1963, five helicopters were shot down in the Mekong Delta region of southern Vietnam. In the battle that followed, three U.S. military advisors were lost alongside eighty-three South Vietnamese soldiers. The U.S. had maintained a limited involvement in Vietnam since sending thirty-five advisors along with the first shipment of military aid in 1950. However, 1963 would prove to be a pivotal year in the United States’ involvement in the region. Originally sent to oversee the distribution of military equipment, then later to help train South Vietnamese soldiers, by 1963 there were sixteen thousand U.S. advisors and special forces in Vietnam, and by then they were accompanying the South Vietnamese army on combat missions. The situation in South Vietnam had been deteriorating for years, and the U.S. involvement had been growing, but most people in the U.S. were not yet paying much attention. More battles followed in the spring and summer, resulting in more U.S. casualties. By the end of 1963, 122 U.S. personnel would be lost, more than the 78 who had been lost throughout the entire involvement in Vietnam up to that point.

At home, 1963 also proved to be a pivotal year. In April, twenty civil rights demonstrators were arrested in Alabama for sit-in protests in downtown Birmingham, and the following month, Dr. Marin Luther King was arrested as he led demonstrators on a march through the downtown. In the months that followed, civil rights demonstrators faced police dogs and fire hoses as the number of protests grew. On June 14, protestors marched in Washington D.C. after Alabama’s governor George Wallace had stood in the doorway of the administration building of the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, in an effort to block the registration of two African American students. The Alabama National Guard was federalized, and Federal troops were deployed to enforce the law and restore order. Civil rights protests and confrontations continued through the summer, culminating in the March on Washington in August, where 250,000 people gathered on the National Mall watched Dr. King deliver his I Have a Dream speech.

As civil rights protests grew in strength at home, and the turmoil engulfing South Vietnam steadily worsened, 1963 ended with the most shocking event of the year: the assassination of President Kennedy on November 22nd, as he drove through Dallas. Two hours after the assassination, with Jacqueline Kennedy standing at his side aboard Air Force One, Lyndon Johnson was sworn in as the 37th President of the United States.

Although the passage of the Civil Rights Act Kennedy had championed earlier that year followed in 1964, so did a dramatic escalation of U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Two years later, there would be ten times more U.S. personnel in Southeast Asia. In time, the budgetary pressure resulting from the escalation of the war in Vietnam, coupled with Johnson’s Great Society programs, would steadily increase political pressure on U.S. monetary policy, and the inflationary consequences stemming from that pressure would eventually impact the value of nearly all financial assets.

In November 1963, however, the Great Inflation was still beyond the horizon. Yet inflation was not completely absent from the minds of those who remained focused on risks after stock prices had risen so far, for so many years.

One week before that fateful day in Dallas, Benjamin Graham, the author of Security Analysis and The Intelligent Investor, delivered a lecture in downtown San Francisco, at the St. Francis Hotel. The lecture covered many topics, including the risk of nuclear war with the Soviet Union, but the main issue he focused on was the nature of the seemingly unstoppable stock market rise, and the assumptions which seemed to be driving it. What makes the discussion particularly interesting for investors today is that it represents the open rumination of one of the greatest investing minds of the 20th century, the father of value investing, wrestling with the early signs of a monetary phase-shift that would fundamentally alter so many of the assumptions long used in assessing investment value.

Although the full implications of this phase shift would not become apparent for another decade, Graham spoke to the audience that November during one of the few genuine “it’s different this time” moments in U.S. economic history.

Up to and including World War II, every major U.S. war had been accompanied by significant inflation throughout the economy. This happened during the revolutionary war, when the Continental Congress authorized the printing of new currency to pay and provision the Continental Army; by 1778, amid widespread food riots, the annual inflation rate in the colonies rose as high as at 29%. Inflation also happened during the War of 1812, when prices rose 21% over three years. During the Civil War, prices rose 58% in dollars, but rose far more in confederate currency (which ultimately ended up worthless). And during World War I, prices rose 49% between 1915 and 1920, as the newly established Federal Reserve dramatically expanded the money supply to support the sale of war bonds.

Yet despite periods of intense inflation during the wars in the 19th and early 20th centuries, there had been no lasting inflation of prices over the long term. The Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis estimates that in 1940, the purchasing value of the U.S. dollar was nearly the same as it was in 1800, when John Adams was President. Wartime inflations had inevitably been followed by periods of deflation when peace returned, and over the course of time this resulted in relatively stable prices.

The period after World War II, however, proved to be different. Wary of the potential for a deflationary economic downturn following the war, such as happened after World War I, and with memories of the deflationary spiral which ushered in the Great Depression still raw, the Federal Reserve and the Treasury Department, at the behest of President Truman, maintained the vast wartime monetary expansion after 1945. Prices had risen 69% during the war as price controls and rationing were instituted, and the inflation continued as price controls were lifted after 1945. For the first time in U.S. history, wartime inflation was not followed by a post-war deflation – it was followed by more inflation.

The lack of post-war deflation was unfortunate for savers. The real value of cash savings had declined precipitously as the Federal Reserve suppressed interest rates below inflation rates during the war, in the interest of funding wartime expenditures at affordable interest rates, and the lack of post-war deflation meant that loss of value of cash savings was permanent.

For Benjamin Graham, expectations of continued inflation resulting from the recent post-war inflationary experience appeared to be one of the main justifications investors were using to continue bidding up stock prices in the early 1960s, as stocks then seemed to be a far safer place to protect savings from inflation than bonds or interest-bearing cash. Yet by 1963 he was openly questioning whether inflation justified the pay any price mentality which was pervasive at the time. After brief introductory remarks to the crowd gathered in the St. Francis Hotel, he dove right into the apparent conflict embedded in investor’s reaction to the post-war inflation:

The continuation of some degree of inflation is certainly probable in the future, and that is the chief reason why most intelligent investors now recognize that some common stocks must be included in their portfolio. However, that is only part of the question of the effect of inflation on investment policy. The fact is that both the extent of inflation and the investor’s reaction to it have varied greatly over the years It is by no means a straight-line matter.

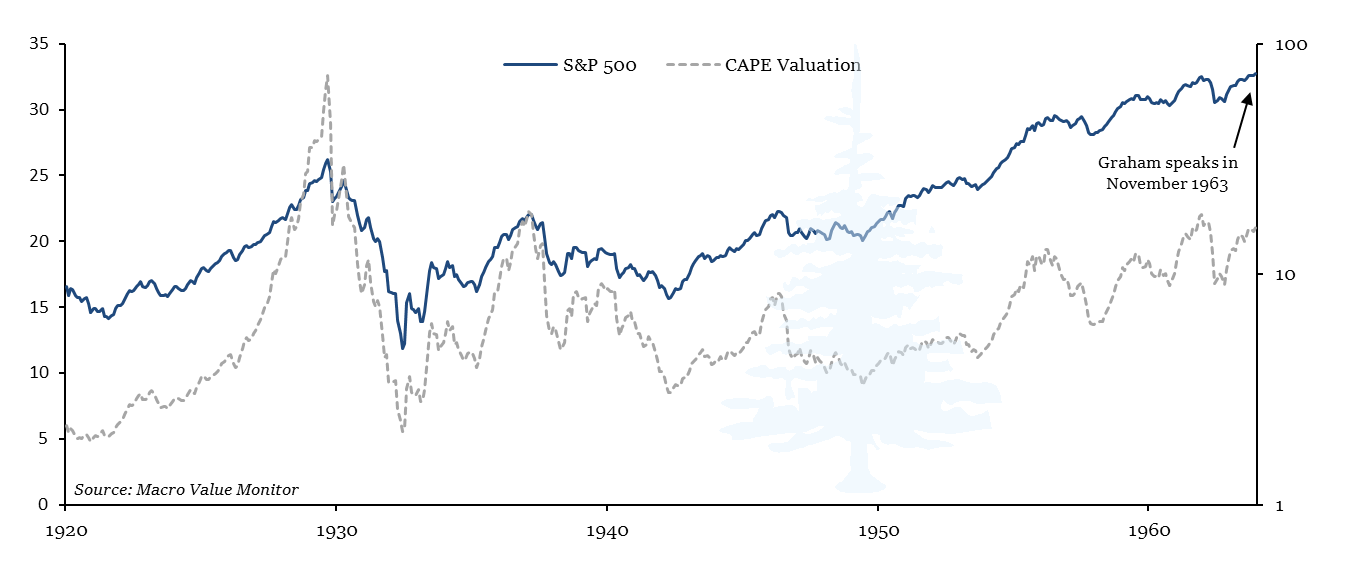

When he spoke that November, the market had been rising for a very long time, and for an investor like Graham, who had navigated the boom years of the 1920s, and also the ruinous market collapse during the Great Depression, remaining cognizant of the market’s underlying value was one of the keys to long-term survival.

It had taken twenty-five years for the market to return to the speculative peak of 1929, and it had only been a few years earlier, in 1958, that the market had risen above its inflation-adjusted price from 1929. Twenty-nine years was a painfully long period of time for the market’s real value to remain below a speculative peak. Regardless of how much inflation was in the future, Graham continued to believe that paying too high a valuation introduced risks which eclipsed many of the long-term benefits of an allocation to equities in lieu of bonds or cash, no matter how low interest rates and bond yields were.

In his speech, Graham attempted to find an adequate explanation for the ongoing strength in the market. Despite valuations being at the highest levels in nearly thirty years, every minor dip the market in the years leading up to 1963 had been followed by a quick and full recovery. Given the novel post-war inflationary outcome, Graham very astutely observed that there was an apparent irony in using inflation as a justification for paying high prices for stocks, because a careful look at the actual history of the market’s performance seemed to indicate that stocks actually disliked higher inflation:

A good example is the most recent one. We have had a small inflation in recent years accompanied by a very large increase in stock-market prices, which seems to be geared not to the inflation experienced but rather to the expectation of greater inflation in the future. You probably know there has been no increase in the wholesale-price index average since 1958. There has indeed been a rise of 6½ percent in the cost of living in the last five years, which of course is not negligible, but it could scarcely in itself be a sound basis for a 100 percent rise in stock prices. Conversely, during the years 1945-1949 we did have a rather explosive kind of inflation – the consumer price index (that is, the “cost of living”) advanced over 33 percent – but during that period stock prices actually had a small decline.

As Graham noted, when inflation had been roaring just after the war in the late 1940s, stock prices had fallen, and valuations were low. Yet in more recent years, when there had been hardly any observable inflation (the Consumer Price Index had risen at a 1.2% annualized rate over the prior five years), stock prices had risen dramatically. This apparent negative correlation with inflation over shorter periods of time seemed at odds with the main justification being used to justify the high market valuations in 1963.

Graham concluded that investors were reading too much into the market’s performance — i.e., they were taking the continued strength of the market to be evidence of inflation to come, instead of actual inflation driving stock prices higher. In other words, investors were assuming the cart was driving the horse:

My conclusion here is that investors’ feelings and reaction regarding inflation are probably more the result of the stock-market action that they have recently experienced that the cause of it. Consequently there is greater danger of investors giving inflation too much weight when the market advances and ignoring it entirely, as they did in 1945-49, when the market declines. This has actually been the history of inflation and stock market behavior ever since 1900.

As the years ahead would show, there would be elements of truth to the inflationary assumptions held by investors at the time, which seemed to be underpinning the strong stock market. Yet Graham’s caution regarding high valuations and the apparent negative relationship between stocks and inflation would also prove enormously consequential for investors in the years that followed — though in the ways neither he nor anyone else could have foreseen at the time.

Graham then conceded it was possible that stocks should perhaps be valued more liberally than in the past, due to the federal government’s apparent commitment to prevent economic depressions. He cited the Employment Act of 1946, and he (once again) astutely observed that one of the effects of the Act would be a reduced likelihood of a depression-like decline in corporate earnings. Such a reduced downside tail-risk for earnings may justify a permanently higher fair value for the stock market, but in his estimation, the market in 1963 had long since risen above his upwardly revised fair value estimate.

While it was clear that the lack of postwar deflation and the reduced likelihood of a catastrophic decline in corporate earnings could result in a higher market valuation, it was also clear to Graham that investors had taken those rational conclusions and irrationally turned them into justifications for buying stocks at any price. As would be shown in the years ahead, while investors seemed to believe a result of the Employment Act was an overall reduction in risk, it was actually a swap of one set of risks for another.

* * *

Little did Graham know, events were already underway in 1963 that would, in due time, bring those new risks to the surface. As he spoke in San Francisco, the monetary trends which would eventually bring down the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates were already causing tremors.

Between 1960 and 1965, dollar liabilities to foreigners increased substantially, while at the same time, the amount of gold the U.S. government held in reserve declined. As a result, by 1965 the U.S. had less than half the gold it needed to settle foreign liabilities, should those foreigners (mainly other central banks) request payment. By 1970, that gold coverage ratio of foreign liabilities would decline further to just 26%.

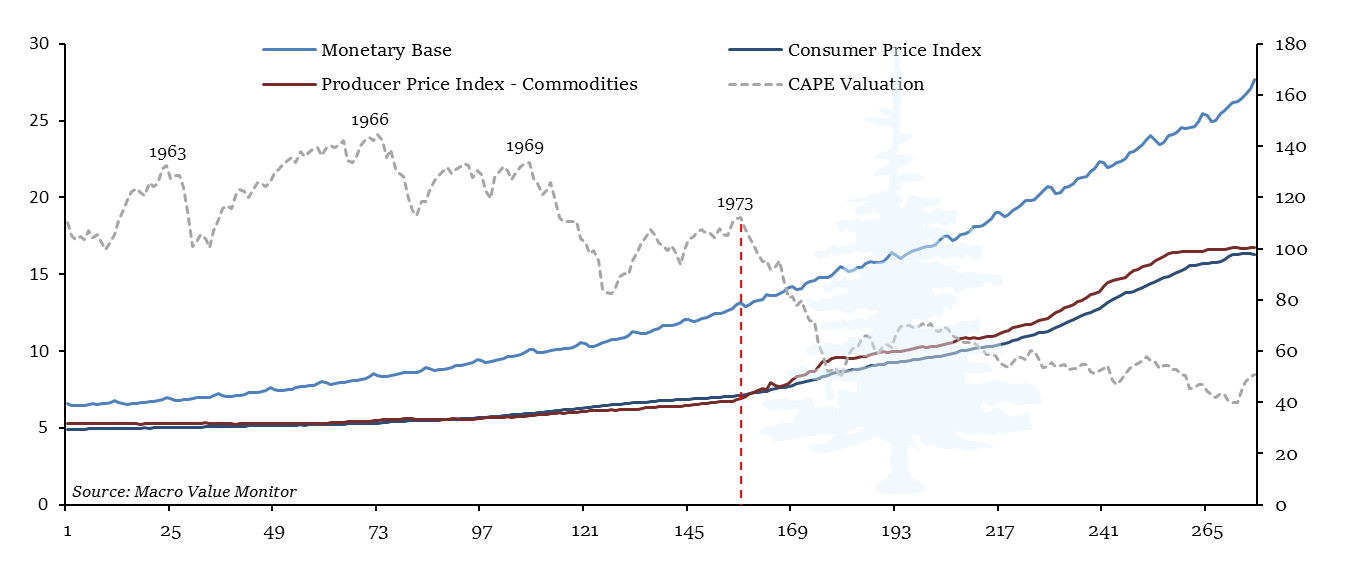

The year 1965 also marked a pivotal moment for interest rates. In what proved to be just the beginning of a fifteen-year-long trend, real short-term interest rates began declining, ultimately falling into negative territory. This decline unfolded even though the Federal Reserve was increasing the Fed Funds rate in order to counter rising inflation.

One of the principal misconceptions that turned the initial economic downturn in 1929 and 1930 into a deflationary depression was a lack of awareness within the Federal Reserve of real, inflation-adjusted interest rates. By 1931, when Benjamin Roth began his diary in Youngstown, Ohio, short-term interest rates had fallen below 1%, and Federal Reserve officials at the time believed that they had done all they could to ease monetary policy; in fact, they believed monetary policy was more accommodative than at any other time up to that point.

What the Fed Governors at the time missed, or were genuinely unconcerned about since prices had remained stable over the long term up to that point, was that with prices falling at an annualized rate of 10%, the real, inflation-adjusted short-term interest rate had risen to over 10%. While they thought monetary policy was extremely loose, it was, in fact, ruinously tight. Thus began the Great Depression.

The Federal Reserve made a similar mistake in the 1960s and 70s, but in the opposite direction. Believing they were tightening monetary policy by increasing the Fed Funds rate in 1965 and in the years that followed, monetary policy was instead becoming progressively looser as the Fed found itself unwilling to accept the economic and political effects of restrictive monetary policy in the face of ever-expanding federal budget deficits. Thus began the Great Inflation.

Ironically, though the markets immediately took notice of the inflationary pivot in 1965, some of the market’s initial reactions served to misleadingly reinforce investors’ beliefs about the attractiveness of stocks amid rising rates.

When a central bank expands the money supply, the newly created money inevitably percolates into the economy unevenly, and the specific manner in which it does so depends on the specific conditions prevailing at the time. Its impact on the financial markets is equally specific to those prevailing conditions, though in the equity market, large monetary expansions have initially ignited animal spirits time and time again. This was certainly the case in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

While the broader market’s valuation quite rationally began to decline as inflation expectations increased, the expanding money supply fomented an increasingly intense search for investments which seemed able to maintain a positive real return. As bond yields began to move higher after 1965, rising inflation’s deleterious effect on a long-term bond’s price became clear. And as real interest rates declined, and then turned negative in 1970, the eroding value of cash also became increasingly clear. As inflation increased and bonds and cash became less and less attractive, and as investors desperately searched for a positive real return, shares of companies which seemed capable of growing their earnings even as consumer prices rose became highly sought after.

This was the era of the Nifty Fifty, stocks which were considered such sure-thing long-term investments amid rising prices that no price was too high to warrant selling them. Price-to-earnings ratios of these stocks rose to incredible heights, which was justified by their unusually bright and stable outlook for real growth. They were known at the time as “one decision” stocks — the only decision anyone had to make was to buy them. By the early 1970s, a decade after the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet had lifted off from its stable postwar level, the speculative fervor surrounding the Nifty Fifty had concentrated and intensified.

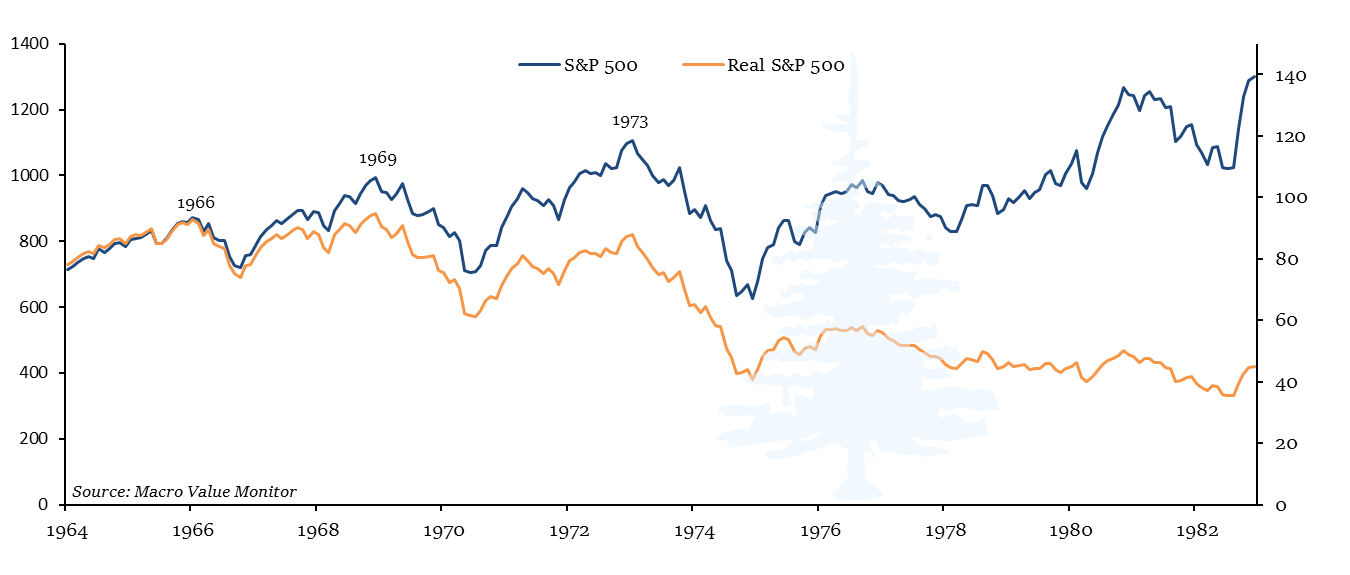

Yet even as the market made a series of new nominal highs, fueled by investors’ hunger for a positive real return, it was steadily losing inflation-adjusted value.

In a way, the increasingly desperate search for shrinking islands of perceived safety was an understandable reaction to the deteriorating market environment. However, Graham’s observations in 1963 proved prescient after the speculative fever finally broke in early 1973 and the Nifty Fifty’s value plummeted along with the rest of the market. In the end, as Graham suggested, paying a sky-high valuation for an equity share in a company, even one which seemed able to indefinitely maintain its real earnings, offered little long-term protection from rising inflation.

* * *

A few years later, one of Graham’s former students, Warren Buffett, penned an article in Forbes outlining his thoughts on why stocks did not hold their real value in the way investors had expected as inflation continued to rise. By the time the article was published in May 1977, the S&P 500 had lost 31% of its real, inflation-adjusted value since Graham had spoken in 1963, even though its nominal price had actually risen 36%.

This divergence between the index’s nominal price, which kept reaching marginal new highs, and its real value, which kept sinking, was part of how investors had been swindled by inflation.

But it was only part. In the article, entitled How Inflation Swindles the Equity Investor, Buffett detailed the mechanics of the inflationary swindle Graham had feared back in 1963. It is worthwhile to read his explanation in his own words (bold has been added):

It is no longer a secret that stocks, like bonds, do poorly in an inflationary environment. We have been in such an environment for most of the past decade, and it has indeed been a time of troubles for stocks. But the reasons for the stock market’s problems in this period are still imperfectly understood…

For many years, the conventional wisdom insisted that stocks were a hedge against inflation. The proposition was rooted in the fact that stocks are not claims against dollars, as bonds are, but represent ownership of companies with productive facilities. These, investors believed, would retain their value in real terms, let the politicians print money as they might.

And why didn’t it turn out that way? The main reason, I believe, is that stocks, in economic substance, are really very similar to bonds…

Looking back, stock investors can think of themselves in the 1946-66 period as having been ladled a truly bountiful triple dip. First, they were the beneficiaries of an underlying corporate return on equity that was far above prevailing interest rates. Second, a significant portion of that return was reinvested for them at rates that were otherwise unattainable. And third, they were afforded an escalating appraisal of underlying equity capital as the first two benefits became widely recognized. This third dip meant that, on top of the basic 12% or so earned by corporations on their equity capital, investors were receiving a bonus as the Dow Jones industrials increased in price from 133% of book value in 1946 to 220% in 1966. Such a marking-up process temporarily allowed investors to achieve a return that exceeded the inherent earning power of the enterprises in which they had invested.

This heaven-on-earth situation finally was “discovered” in the mid-1960s by many major investing institutions. But just as these financial elephants began trampling on one another in their rush to equities, we entered an era of accelerating inflation and higher interest rates. Quite logically, the marking-up process began to reverse itself. Rising interest rates ruthlessly reduced the value of all existing fixed-coupon investments. And as long-term corporate bond rates began moving up (eventually reaching the 10% area), both the equity return of 12% and the reinvestment “privilege” began to look different.

Stocks are quite properly thought of as riskier than bonds. While that equity coupon is more or less fixed over periods of time, it does fluctuate somewhat from year to year. Investors’ attitudes about the future can be affected substantially, although frequently erroneously, by those yearly changes. Stocks are also riskier because they come equipped with infinite maturities. (Even your friendly broker wouldn’t have the nerve to peddle a 100-year bond, if he had any available, as “safe.”) Because of the additional risk, the natural reaction of investors is to expect an equity return that is comfortably above the bond return — and 12% on equity versus, say, 10% on bonds issued by the same corporate universe does not seem to qualify as comfortable. As the spread narrows, equity investors start looking for the exits.

But, of course, as a group they can’t get out. All they can achieve is a lot of movement, substantial frictional costs, and a new, much lower level of valuation, reflecting the lessened attractiveness of the 12% equity coupon under inflationary conditions. Bond investors have had a succession of shocks over the past decade in the course of discovering that there is no magic attached to any given coupon level: at 6%, or 8%, or 10%, bonds can still collapse in price. Stock investors, who are in general not aware that they too have a “coupon,” are still receiving their education on this point.

When Graham delivered his speech in 1963, he had no inkling of the events that would lead to inflation rising as much as it did in the 1970s. He did not know, for instance, that Lyndon Johnson would become president one week later. He also did not know that five years later there would be more than half a million U.S. soldiers in Vietnam, fighting a war in a far-off land at enormous expense. And in all likelihood, he could not have conceived that a mere eight years later the U.S. would be forced off the gold standard, and for the first time the developed world would settle on a regime of floating fiat currencies, unanchored to any firm store of value. On November 15, 1963, all of those events lay in the distant future.

What Graham intuitively understood, however, is that in an environment of low interest rates, low inflation, and high equity market valuations, there is a significant underlying risk embedded in stock prices. He also understood, based on the inflationary postwar experience, that the dual mandate of the Employment Act of 1946 may have fundamentally tilted the economic landscape toward perpetual inflation.

Yet while investors in the early 1960s seemed to have perceived this tilt toward inflation, they also seemed to have concluded that stocks were attractive in the long run regardless of how high valuations were. Therein lies the key fallacy that Graham pointed to in 1963, and which Buffett later offered a more detailed explanation of in 1977: the “marking up” process as inflation rates and interest rates fall creates a tremendous tailwind for stocks, but when the process reverses as the inflation rate rises, the resulting headwind is equally powerful.

Between the time of Graham’s lecture at the St. Francis Hotel and Buffett’s published thoughts on the inflationary swindle in Fortune, the S&P 500 had lost real, inflation-adjusted value at an average rate of 2.7% per year. There is no doubt a long-term decline in real value was not the result eager investors in 1963 were anticipating. In the equivalent amount of time leading up to 1963, the S&P 500 had risen at a real annualized rate of 8.6%, the result of Buffett’s bountiful triple dip. Investors in 1963 almost certainly expected the positive returns to continue. However, when the bountiful triple dip reversed, the inflationary swindle of equity investors began.

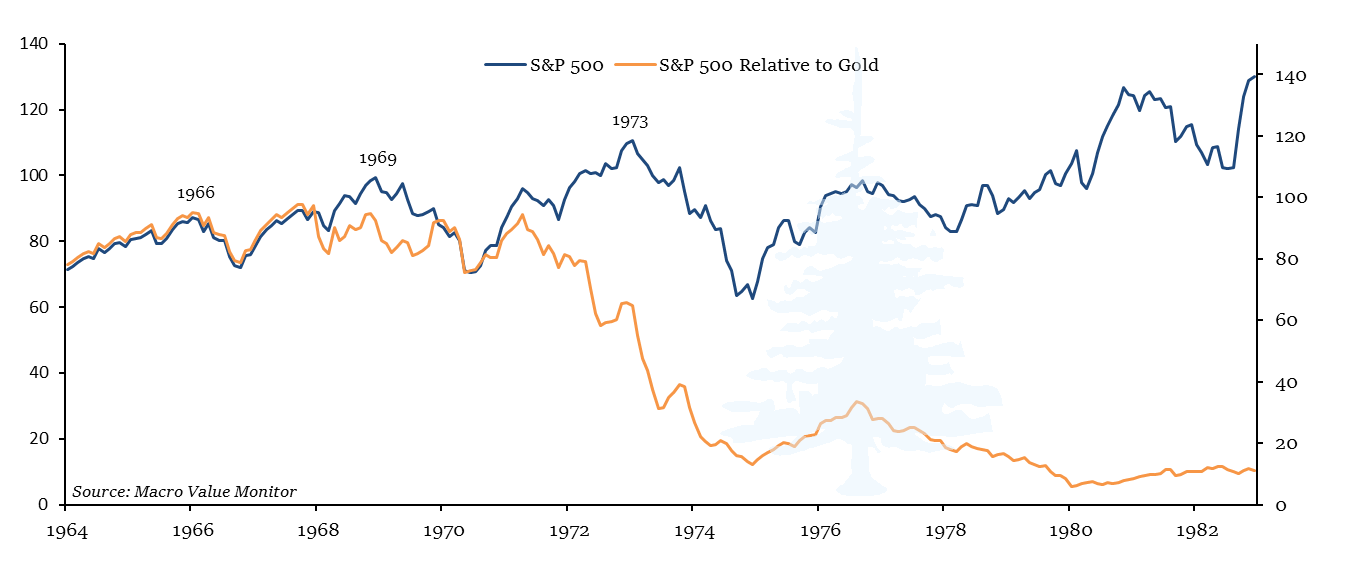

Yet the inflation-adjusted decline did not represent the entirety of the swindle of equity investors after 1963: stocks declined far more against real assets. In between the time Graham spoke in 1963 and Buffett published his article in 1977, the S&P 500 lost value at an annualized rate of more than 15% against gold, for a cumulative loss of 89%. By the time the markets had fully priced in the impact of The Great Inflation in 1980, the S&P 500 had declined 92% against gold. Not coincidentally, the loss of real value during the Great Inflation was similar in magnitude to the value lost in the depths of the Great Depression, a pattern which would repeat again in the decade after the peak of the tech bubble in 2000.

However, the 92% erosion of real value during the 1960s and 70s was not a smooth progression from beginning to end: the extent of the decline did not become evident until President Nixon shocked the world by closing the gold window on August 15, 1971.

Until that moment, a gradual increase of financial stresses had quietly accumulated under the veneer of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates. After that moment, the erosion of value unfolded suddenly: the S&P 500 lost 78% of its real value in just three years following the Nixon Shock, as the stresses that had accumulated over the prior decade flooded through market prices.

* * *

The above is part 1 of the Summer 2022 issue of The Macro Value Monitor, a publication focusing on Monetary History, Market Myths, Investing Legends, and Real Global Value.

Part II, Prospective Market Returns and Prudent Allocations in the Midst of the First Inflationary Bear Market in Four Decades, is available on Substack.

The content of this document is provided as general information and is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment or other advice. This material is not to be construed as a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any security, financial product, instrument or to participate in any particular trading strategy. Not all securities, products or services described are available in all countries, and nothing herein constitutes an offer or solicitation of any securities, products or services in any jurisdiction where their offer or sale is not qualified or exempt from registration or otherwise legally permissible.

Although the material herein is based upon information considered reliable and up-to-date, Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC does not assure that this material is accurate, current, or complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. Content in this document may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted, in whole or in part, without prior written consent from Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC — which is usually gladly given, as long as its use includes clear and proper attribution. Contact us for more information.

© Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC

How an Inflationary End to the Bountiful Triple Dip Swindled Equity Investors

August 10, 2022

The continuation of some degree of inflation is certainly probable in the future, and that is the chief reason why most intelligent investors now recognize that some common stocks must be included in their portfolio. However, that is only part of the question of the effect of inflation on investment policy…

[T]he argument that common stocks are and always will be attractive, including the present time, because of their excellent record since 1949 – involves in those terms a very fundamental and important fallacy. This is the idea that the better the past record of the stock market as such, the more certain it is that common stocks are sound investments for the future… But you cannot say that the fact that the stock market has risen continuously (or slightly irregularly) over a long period in the past is a guarantee that it will continue to act that way in the future. As I see it, the real truth is exactly the opposite, for the higher the stock market advances the more reason there is to mistrust its future action…

~ Benjamin Graham, November 15, 1963

‘How did you go bankrupt?’ Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.

~ From The Sun Also Rises, by Ernest Hemingway

The year 1963, not unlike the years we have experienced recently, was a period of growing turbulence in the United States. Both at home and abroad, seeds were being sown for social, political and economic changes that would come to define the era ahead, in ways few could then imagine. Yet at the time, those changes were still beyond the horizon, and for most of the country, and especially for those in the financial markets, 1963 seemed like it was the best of times.

The stock market was a potent symbol of that best of times feeling. Over the previous fourteen years, stocks had been rising almost without interruption, and the equity market had quadrupled since the dust had settled after the Second World War. Interest rates were comfortably low as 1963 began, as was inflation. Consumer prices had risen just 1.3% over the past year, and the rationing, price controls and inflation during and after the war were a distant memory. So was the debilitating unemployment of the Great Depression.

The torch had recently been passed to John F. Kennedy, and his cadre of the best and the brightest seemed to embody a new era of optimism. The prior summer Kennedy had announced the U.S. would land on the moon before the end of the decade, and the Mercury missions were already carrying Americans into space. And although the Cold War with the Soviet Union hung overhead, Kennedy had just convinced Khrushchev to remove the nuclear missiles that had been secretly installed in Cuba. By the end of 1962, having faced down the Soviet Union, and with the stock market fully recovering — yet again — from another selloff, it seemed Kennedy and the U.S. were poised to continue on a firm upward trajectory.

As 1963 began, however, events began to unfold that would prove to be harbingers of more difficult times to come.

On the second day of January, 1963, five helicopters were shot down in the Mekong Delta region of southern Vietnam. In the battle that followed, three U.S. military advisors were lost alongside eighty-three South Vietnamese soldiers. The U.S. had maintained a limited involvement in Vietnam since sending thirty-five advisors along with the first shipment of military aid in 1950. However, 1963 would prove to be a pivotal year in the United States’ involvement in the region. Originally sent to oversee the distribution of military equipment, then later to help train South Vietnamese soldiers, by 1963 there were sixteen thousand U.S. advisors and special forces in Vietnam, and by then they were accompanying the South Vietnamese army on combat missions. The situation in South Vietnam had been deteriorating for years, and the U.S. involvement had been growing, but most people in the U.S. were not yet paying much attention. More battles followed in the spring and summer, resulting in more U.S. casualties. By the end of 1963, 122 U.S. personnel would be lost, more than the 78 who had been lost throughout the entire involvement in Vietnam up to that point.

At home, 1963 also proved to be a pivotal year. In April, twenty civil rights demonstrators were arrested in Alabama for sit-in protests in downtown Birmingham, and the following month, Dr. Marin Luther King was arrested as he led demonstrators on a march through the downtown. In the months that followed, civil rights demonstrators faced police dogs and fire hoses as the number of protests grew. On June 14, protestors marched in Washington D.C. after Alabama’s governor George Wallace had stood in the doorway of the administration building of the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, in an effort to block the registration of two African American students. The Alabama National Guard was federalized, and Federal troops were deployed to enforce the law and restore order. Civil rights protests and confrontations continued through the summer, culminating in the March on Washington in August, where 250,000 people gathered on the National Mall watched Dr. King deliver his I Have a Dream speech.

As civil rights protests grew in strength at home, and the turmoil engulfing South Vietnam steadily worsened, 1963 ended with the most shocking event of the year: the assassination of President Kennedy on November 22nd, as he drove through Dallas. Two hours after the assassination, with Jacqueline Kennedy standing at his side aboard Air Force One, Lyndon Johnson was sworn in as the 37th President of the United States.

Although the passage of the Civil Rights Act Kennedy had championed earlier that year followed in 1964, so did a dramatic escalation of U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Two years later, there would be ten times more U.S. personnel in Southeast Asia. In time, the budgetary pressure resulting from the escalation of the war in Vietnam, coupled with Johnson’s Great Society programs, would steadily increase political pressure on U.S. monetary policy, and the inflationary consequences stemming from that pressure would eventually impact the value of nearly all financial assets.

In November 1963, however, the Great Inflation was still beyond the horizon. Yet inflation was not completely absent from the minds of those who remained focused on risks after stock prices had risen so far, for so many years.

One week before that fateful day in Dallas, Benjamin Graham, the author of Security Analysis and The Intelligent Investor, delivered a lecture in downtown San Francisco, at the St. Francis Hotel. The lecture covered many topics, including the risk of nuclear war with the Soviet Union, but the main issue he focused on was the nature of the seemingly unstoppable stock market rise, and the assumptions which seemed to be driving it. What makes the discussion particularly interesting for investors today is that it represents the open rumination of one of the greatest investing minds of the 20th century, the father of value investing, wrestling with the early signs of a monetary phase-shift that would fundamentally alter so many of the assumptions long used in assessing investment value.

Although the full implications of this phase shift would not become apparent for another decade, Graham spoke to the audience that November during one of the few genuine “it’s different this time” moments in U.S. economic history.

Up to and including World War II, every major U.S. war had been accompanied by significant inflation throughout the economy. This happened during the revolutionary war, when the Continental Congress authorized the printing of new currency to pay and provision the Continental Army; by 1778, amid widespread food riots, the annual inflation rate in the colonies rose as high as at 29%. Inflation also happened during the War of 1812, when prices rose 21% over three years. During the Civil War, prices rose 58% in dollars, but rose far more in confederate currency (which ultimately ended up worthless). And during World War I, prices rose 49% between 1915 and 1920, as the newly established Federal Reserve dramatically expanded the money supply to support the sale of war bonds.

Yet despite periods of intense inflation during the wars in the 19th and early 20th centuries, there had been no lasting inflation of prices over the long term. The Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis estimates that in 1940, the purchasing value of the U.S. dollar was nearly the same as it was in 1800, when John Adams was President. Wartime inflations had inevitably been followed by periods of deflation when peace returned, and over the course of time this resulted in relatively stable prices.

The period after World War II, however, proved to be different. Wary of the potential for a deflationary economic downturn following the war, such as happened after World War I, and with memories of the deflationary spiral which ushered in the Great Depression still raw, the Federal Reserve and the Treasury Department, at the behest of President Truman, maintained the vast wartime monetary expansion after 1945. Prices had risen 69% during the war as price controls and rationing were instituted, and the inflation continued as price controls were lifted after 1945. For the first time in U.S. history, wartime inflation was not followed by a post-war deflation – it was followed by more inflation.

The lack of post-war deflation was unfortunate for savers. The real value of cash savings had declined precipitously as the Federal Reserve suppressed interest rates below inflation rates during the war, in the interest of funding wartime expenditures at affordable interest rates, and the lack of post-war deflation meant that loss of value of cash savings was permanent.

For Benjamin Graham, expectations of continued inflation resulting from the recent post-war inflationary experience appeared to be one of the main justifications investors were using to continue bidding up stock prices in the early 1960s, as stocks then seemed to be a far safer place to protect savings from inflation than bonds or interest-bearing cash. Yet by 1963 he was openly questioning whether inflation justified the pay any price mentality which was pervasive at the time. After brief introductory remarks to the crowd gathered in the St. Francis Hotel, he dove right into the apparent conflict embedded in investor’s reaction to the post-war inflation:

The continuation of some degree of inflation is certainly probable in the future, and that is the chief reason why most intelligent investors now recognize that some common stocks must be included in their portfolio. However, that is only part of the question of the effect of inflation on investment policy. The fact is that both the extent of inflation and the investor’s reaction to it have varied greatly over the years It is by no means a straight-line matter.

When he spoke that November, the market had been rising for a very long time, and for an investor like Graham, who had navigated the boom years of the 1920s, and also the ruinous market collapse during the Great Depression, remaining cognizant of the market’s underlying value was one of the keys to long-term survival.

It had taken twenty-five years for the market to return to the speculative peak of 1929, and it had only been a few years earlier, in 1958, that the market had risen above its inflation-adjusted price from 1929. Twenty-nine years was a painfully long period of time for the market’s real value to remain below a speculative peak. Regardless of how much inflation was in the future, Graham continued to believe that paying too high a valuation introduced risks which eclipsed many of the long-term benefits of an allocation to equities in lieu of bonds or cash, no matter how low interest rates and bond yields were.

In his speech, Graham attempted to find an adequate explanation for the ongoing strength in the market. Despite valuations being at the highest levels in nearly thirty years, every minor dip the market in the years leading up to 1963 had been followed by a quick and full recovery. Given the novel post-war inflationary outcome, Graham very astutely observed that there was an apparent irony in using inflation as a justification for paying high prices for stocks, because a careful look at the actual history of the market’s performance seemed to indicate that stocks actually disliked higher inflation:

A good example is the most recent one. We have had a small inflation in recent years accompanied by a very large increase in stock-market prices, which seems to be geared not to the inflation experienced but rather to the expectation of greater inflation in the future. You probably know there has been no increase in the wholesale-price index average since 1958. There has indeed been a rise of 6½ percent in the cost of living in the last five years, which of course is not negligible, but it could scarcely in itself be a sound basis for a 100 percent rise in stock prices. Conversely, during the years 1945-1949 we did have a rather explosive kind of inflation – the consumer price index (that is, the “cost of living”) advanced over 33 percent – but during that period stock prices actually had a small decline.

As Graham noted, when inflation had been roaring just after the war in the late 1940s, stock prices had fallen, and valuations were low. Yet in more recent years, when there had been hardly any observable inflation (the Consumer Price Index had risen at a 1.2% annualized rate over the prior five years), stock prices had risen dramatically. This apparent negative correlation with inflation over shorter periods of time seemed at odds with the main justification being used to justify the high market valuations in 1963.

Graham concluded that investors were reading too much into the market’s performance — i.e., they were taking the continued strength of the market to be evidence of inflation to come, instead of actual inflation driving stock prices higher. In other words, investors were assuming the cart was driving the horse:

My conclusion here is that investors’ feelings and reaction regarding inflation are probably more the result of the stock-market action that they have recently experienced that the cause of it. Consequently there is greater danger of investors giving inflation too much weight when the market advances and ignoring it entirely, as they did in 1945-49, when the market declines. This has actually been the history of inflation and stock market behavior ever since 1900.

As the years ahead would show, there would be elements of truth to the inflationary assumptions held by investors at the time, which seemed to be underpinning the strong stock market. Yet Graham’s caution regarding high valuations and the apparent negative relationship between stocks and inflation would also prove enormously consequential for investors in the years that followed — though in the ways neither he nor anyone else could have foreseen at the time.

Graham then conceded it was possible that stocks should perhaps be valued more liberally than in the past, due to the federal government’s apparent commitment to prevent economic depressions. He cited the Employment Act of 1946, and he (once again) astutely observed that one of the effects of the Act would be a reduced likelihood of a depression-like decline in corporate earnings. Such a reduced downside tail-risk for earnings may justify a permanently higher fair value for the stock market, but in his estimation, the market in 1963 had long since risen above his upwardly revised fair value estimate.

While it was clear that the lack of postwar deflation and the reduced likelihood of a catastrophic decline in corporate earnings could result in a higher market valuation, it was also clear to Graham that investors had taken those rational conclusions and irrationally turned them into justifications for buying stocks at any price. As would be shown in the years ahead, while investors seemed to believe a result of the Employment Act was an overall reduction in risk, it was actually a swap of one set of risks for another.

* * *

Little did Graham know, events were already underway in 1963 that would, in due time, bring those new risks to the surface. As he spoke in San Francisco, the monetary trends which would eventually bring down the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates were already causing tremors.

Between 1960 and 1965, dollar liabilities to foreigners increased substantially, while at the same time, the amount of gold the U.S. government held in reserve declined. As a result, by 1965 the U.S. had less than half the gold it needed to settle foreign liabilities, should those foreigners (mainly other central banks) request payment. By 1970, that gold coverage ratio of foreign liabilities would decline further to just 26%.

The year 1965 also marked a pivotal moment for interest rates. In what proved to be just the beginning of a fifteen-year-long trend, real short-term interest rates began declining, ultimately falling into negative territory. This decline unfolded even though the Federal Reserve was increasing the Fed Funds rate in order to counter rising inflation.

One of the principal misconceptions that turned the initial economic downturn in 1929 and 1930 into a deflationary depression was a lack of awareness within the Federal Reserve of real, inflation-adjusted interest rates. By 1931, when Benjamin Roth began his diary in Youngstown, Ohio, short-term interest rates had fallen below 1%, and Federal Reserve officials at the time believed that they had done all they could to ease monetary policy; in fact, they believed monetary policy was more accommodative than at any other time up to that point.

What the Fed Governors at the time missed, or were genuinely unconcerned about since prices had remained stable over the long term up to that point, was that with prices falling at an annualized rate of 10%, the real, inflation-adjusted short-term interest rate had risen to over 10%. While they thought monetary policy was extremely loose, it was, in fact, ruinously tight. Thus began the Great Depression.

The Federal Reserve made a similar mistake in the 1960s and 70s, but in the opposite direction. Believing they were tightening monetary policy by increasing the Fed Funds rate in 1965 and in the years that followed, monetary policy was instead becoming progressively looser as the Fed found itself unwilling to accept the economic and political effects of restrictive monetary policy in the face of ever-expanding federal budget deficits. Thus began the Great Inflation.

Ironically, though the markets immediately took notice of the inflationary pivot in 1965, some of the market’s initial reactions served to misleadingly reinforce investors’ beliefs about the attractiveness of stocks amid rising rates.

When a central bank expands the money supply, the newly created money inevitably percolates into the economy unevenly, and the specific manner in which it does so depends on the specific conditions prevailing at the time. Its impact on the financial markets is equally specific to those prevailing conditions, though in the equity market, large monetary expansions have initially ignited animal spirits time and time again. This was certainly the case in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

While the broader market’s valuation quite rationally began to decline as inflation expectations increased, the expanding money supply fomented an increasingly intense search for investments which seemed able to maintain a positive real return. As bond yields began to move higher after 1965, rising inflation’s deleterious effect on a long-term bond’s price became clear. And as real interest rates declined, and then turned negative in 1970, the eroding value of cash also became increasingly clear. As inflation increased and bonds and cash became less and less attractive, and as investors desperately searched for a positive real return, shares of companies which seemed capable of growing their earnings even as consumer prices rose became highly sought after.

This was the era of the Nifty Fifty, stocks which were considered such sure-thing long-term investments amid rising prices that no price was too high to warrant selling them. Price-to-earnings ratios of these stocks rose to incredible heights, which was justified by their unusually bright and stable outlook for real growth. They were known at the time as “one decision” stocks — the only decision anyone had to make was to buy them. By the early 1970s, a decade after the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet had lifted off from its stable postwar level, the speculative fervor surrounding the Nifty Fifty had concentrated and intensified.

Yet even as the market made a series of new nominal highs, fueled by investors’ hunger for a positive real return, it was steadily losing inflation-adjusted value.

In a way, the increasingly desperate search for shrinking islands of perceived safety was an understandable reaction to the deteriorating market environment. However, Graham’s observations in 1963 proved prescient after the speculative fever finally broke in early 1973 and the Nifty Fifty’s value plummeted along with the rest of the market. In the end, as Graham suggested, paying a sky-high valuation for an equity share in a company, even one which seemed able to indefinitely maintain its real earnings, offered little long-term protection from rising inflation.

* * *

A few years later, one of Graham’s former students, Warren Buffett, penned an article in Forbes outlining his thoughts on why stocks did not hold their real value in the way investors had expected as inflation continued to rise. By the time the article was published in May 1977, the S&P 500 had lost 31% of its real, inflation-adjusted value since Graham had spoken in 1963, even though its nominal price had actually risen 36%.

This divergence between the index’s nominal price, which kept reaching marginal new highs, and its real value, which kept sinking, was part of how investors had been swindled by inflation.

But it was only part. In the article, entitled How Inflation Swindles the Equity Investor, Buffett detailed the mechanics of the inflationary swindle Graham had feared back in 1963. It is worthwhile to read his explanation in his own words (bold has been added):

It is no longer a secret that stocks, like bonds, do poorly in an inflationary environment. We have been in such an environment for most of the past decade, and it has indeed been a time of troubles for stocks. But the reasons for the stock market’s problems in this period are still imperfectly understood…

For many years, the conventional wisdom insisted that stocks were a hedge against inflation. The proposition was rooted in the fact that stocks are not claims against dollars, as bonds are, but represent ownership of companies with productive facilities. These, investors believed, would retain their value in real terms, let the politicians print money as they might.

And why didn’t it turn out that way? The main reason, I believe, is that stocks, in economic substance, are really very similar to bonds…

Looking back, stock investors can think of themselves in the 1946-66 period as having been ladled a truly bountiful triple dip. First, they were the beneficiaries of an underlying corporate return on equity that was far above prevailing interest rates. Second, a significant portion of that return was reinvested for them at rates that were otherwise unattainable. And third, they were afforded an escalating appraisal of underlying equity capital as the first two benefits became widely recognized. This third dip meant that, on top of the basic 12% or so earned by corporations on their equity capital, investors were receiving a bonus as the Dow Jones industrials increased in price from 133% of book value in 1946 to 220% in 1966. Such a marking-up process temporarily allowed investors to achieve a return that exceeded the inherent earning power of the enterprises in which they had invested.

This heaven-on-earth situation finally was “discovered” in the mid-1960s by many major investing institutions. But just as these financial elephants began trampling on one another in their rush to equities, we entered an era of accelerating inflation and higher interest rates. Quite logically, the marking-up process began to reverse itself. Rising interest rates ruthlessly reduced the value of all existing fixed-coupon investments. And as long-term corporate bond rates began moving up (eventually reaching the 10% area), both the equity return of 12% and the reinvestment “privilege” began to look different.

Stocks are quite properly thought of as riskier than bonds. While that equity coupon is more or less fixed over periods of time, it does fluctuate somewhat from year to year. Investors’ attitudes about the future can be affected substantially, although frequently erroneously, by those yearly changes. Stocks are also riskier because they come equipped with infinite maturities. (Even your friendly broker wouldn’t have the nerve to peddle a 100-year bond, if he had any available, as “safe.”) Because of the additional risk, the natural reaction of investors is to expect an equity return that is comfortably above the bond return — and 12% on equity versus, say, 10% on bonds issued by the same corporate universe does not seem to qualify as comfortable. As the spread narrows, equity investors start looking for the exits.

But, of course, as a group they can’t get out. All they can achieve is a lot of movement, substantial frictional costs, and a new, much lower level of valuation, reflecting the lessened attractiveness of the 12% equity coupon under inflationary conditions. Bond investors have had a succession of shocks over the past decade in the course of discovering that there is no magic attached to any given coupon level: at 6%, or 8%, or 10%, bonds can still collapse in price. Stock investors, who are in general not aware that they too have a “coupon,” are still receiving their education on this point.

When Graham delivered his speech in 1963, he had no inkling of the events that would lead to inflation rising as much as it did in the 1970s. He did not know, for instance, that Lyndon Johnson would become president one week later. He also did not know that five years later there would be more than half a million U.S. soldiers in Vietnam, fighting a war in a far-off land at enormous expense. And in all likelihood, he could not have conceived that a mere eight years later the U.S. would be forced off the gold standard, and for the first time the developed world would settle on a regime of floating fiat currencies, unanchored to any firm store of value. On November 15, 1963, all of those events lay in the distant future.

What Graham intuitively understood, however, is that in an environment of low interest rates, low inflation, and high equity market valuations, there is a significant underlying risk embedded in stock prices. He also understood, based on the inflationary postwar experience, that the dual mandate of the Employment Act of 1946 may have fundamentally tilted the economic landscape toward perpetual inflation.

Yet while investors in the early 1960s seemed to have perceived this tilt toward inflation, they also seemed to have concluded that stocks were attractive in the long run regardless of how high valuations were. Therein lies the key fallacy that Graham pointed to in 1963, and which Buffett later offered a more detailed explanation of in 1977: the “marking up” process as inflation rates and interest rates fall creates a tremendous tailwind for stocks, but when the process reverses as the inflation rate rises, the resulting headwind is equally powerful.

Between the time of Graham’s lecture at the St. Francis Hotel and Buffett’s published thoughts on the inflationary swindle in Fortune, the S&P 500 had lost real, inflation-adjusted value at an average rate of 2.7% per year. There is no doubt a long-term decline in real value was not the result eager investors in 1963 were anticipating. In the equivalent amount of time leading up to 1963, the S&P 500 had risen at a real annualized rate of 8.6%, the result of Buffett’s bountiful triple dip. Investors in 1963 almost certainly expected the positive returns to continue. However, when the bountiful triple dip reversed, the inflationary swindle of equity investors began.

Yet the inflation-adjusted decline did not represent the entirety of the swindle of equity investors after 1963: stocks declined far more against real assets. In between the time Graham spoke in 1963 and Buffett published his article in 1977, the S&P 500 lost value at an annualized rate of more than 15% against gold, for a cumulative loss of 89%. By the time the markets had fully priced in the impact of The Great Inflation in 1980, the S&P 500 had declined 92% against gold. Not coincidentally, the loss of real value during the Great Inflation was similar in magnitude to the value lost in the depths of the Great Depression, a pattern which would repeat again in the decade after the peak of the tech bubble in 2000.

However, the 92% erosion of real value during the 1960s and 70s was not a smooth progression from beginning to end: the extent of the decline did not become evident until President Nixon shocked the world by closing the gold window on August 15, 1971.

Until that moment, a gradual increase of financial stresses had quietly accumulated under the veneer of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates. After that moment, the erosion of value unfolded suddenly: the S&P 500 lost 78% of its real value in just three years following the Nixon Shock, as the stresses that had accumulated over the prior decade flooded through market prices.

* * *

The above is part 1 of the Summer 2022 issue of The Macro Value Monitor, a publication focusing on Monetary History, Market Myths, Investing Legends, and Real Global Value.

Part II, Prospective Market Returns and Prudent Allocations in the Midst of the First Inflationary Bear Market in Four Decades, is available on Substack.

The content of this document is provided as general information and is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment or other advice. This material is not to be construed as a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any security, financial product, instrument or to participate in any particular trading strategy. Not all securities, products or services described are available in all countries, and nothing herein constitutes an offer or solicitation of any securities, products or services in any jurisdiction where their offer or sale is not qualified or exempt from registration or otherwise legally permissible.

Although the material herein is based upon information considered reliable and up-to-date, Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC does not assure that this material is accurate, current, or complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. Content in this document may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted, in whole or in part, without prior written consent from Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC — which is usually gladly given, as long as its use includes clear and proper attribution. Contact us for more information.

© Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC

Investment Management

Before investing, we will discuss your goals and risk tolerances with you to see if a separately managed account at Sitka Pacific would be a good fit. To contact us for a free consultation, visit Getting Started.

Macro Value Monitor

To read a selection of recent client letters and be alerted when new letters are posted to our public site, visit Recent Client Letters.