The Time Has Finally Come

4th Quarter, 2024

After persisting for as long as two years in the US, the so-called inversion in yield curves — an unusual situation where rates on short-term debt exceed those of their longer-term counterparts — is unwinding in many parts of the world. The normalizing, or steepening, trend first surfaced in July in UK gilts, followed by US Treasuries a month later. Now it is happening in German and Canadian bond markets as well.

The shift is taking place as central banks start to lower benchmark interest rates after years of keeping them elevated…

~ Bloomberg, September 24, 2024

The time has come for policy to adjust. The direction of travel is clear, and the timing and pace of rate cuts will depend on incoming data, the evolving outlook, and the balance of risks.

~ Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, August 23, 2024

* * *

In January 2022, we ventured three hundred years back in time to an episode that has long been considered the classic example of mania in the early annals of market history. The Mississippi Bubble in 1720 is the leading early example of a modern stock market bubble. Although it involved only a single stock, the Company of the West, it remains the most well-documented early episode of public mania, followed by a mass panic and a market crash.

As dramatic as the rise and subsequent collapse was, the primary reason we spent time discussing the Mississippi Bubble was not the boom and bust in Company of the West shares that were traded on the narrow rue Quincampoix. The primary reason, the reason which remains particularly relevant to investors today, was the monetary story underlying the public mania.

If you recall, John Law formed the Banque Royale in Paris so that he could begin issuing paper banknotes. In the beginning, the banknotes were used as receipts for gold and silver coins deposited at the bank, and every circulating banknote represented hard money on deposit.

Law intended that this scheme would solve some very real problems in the French economy. The authentication of coins had been an issue for centuries, and the new paper banknotes were to provide an assurance that the coins represented by the notes had been assayed by the bank and found to contain all the gold and silver they were supposed to. In theory, this would reduce the time, effort, and cost of transactions: those who paid in banknotes, instead of coins, would then be able to trust that the Banque Royale had guaranteed the value of the money they received.

As time went on, however, the Banque Royale undercut that trust by issuing more banknotes than the amount of gold and silver held at the bank – many more banknotes. This excess issuance initially seemed to solve hosts of other problems that had long plagued, and seemingly limited, France’s economy. Capital for projects was no longer so scarce, and citizens throughout France were delighted to realize they suddenly had much more money at their disposal. They initially used this new money to rabidly buy more Company of the West shares, and the lucky early holders of those shares who cashed out began using their newfound wealth to buy homes in Paris, large country estates, and luxury goods of every kind. Prices for those assets then began to soar as well.

The more banknotes the Banque Royale printed and issued to the public, the wealthier everyone seemed to become. It appeared as if the old laws governing economics and money had finally been relegated to the past. Law was credited with unleashing a flood of prosperity onto the citizens of Paris, and the French economy continued to thrive as wealth and spending soared.

When prices began to rise throughout the broader French economy, however, the first cracks appeared in the trust of the very banknotes that had ignited the boom.

It was one thing when asset prices were soaring – that made owners of shares, homes, and land feel immensely wealthy. It was quite another thing when prices for everyday goods began rising. That just made daily life more expensive, and more difficult. It also began sparking questions among the frustrated citizenry – questions about what, exactly, was making the prices of bread, fuel, and feed rise so much.

Amid the early questioning, a handful of wealthy citizens reached their own conclusions in late 1719, and stealthily began exchanging their banknotes back to gold. The only problem was, by that time there was only enough gold in the Banque Royale to redeem a small fraction of the notes in circulation. As the early trickle out of banknotes turned into a run in 1720, gold’s price began to rise.

* * *

While a narrative from three centuries ago may seem like ancient history, it was not too long ago that a similar progression unfolded in the U.S., for reasons similar to those in France in 1720.

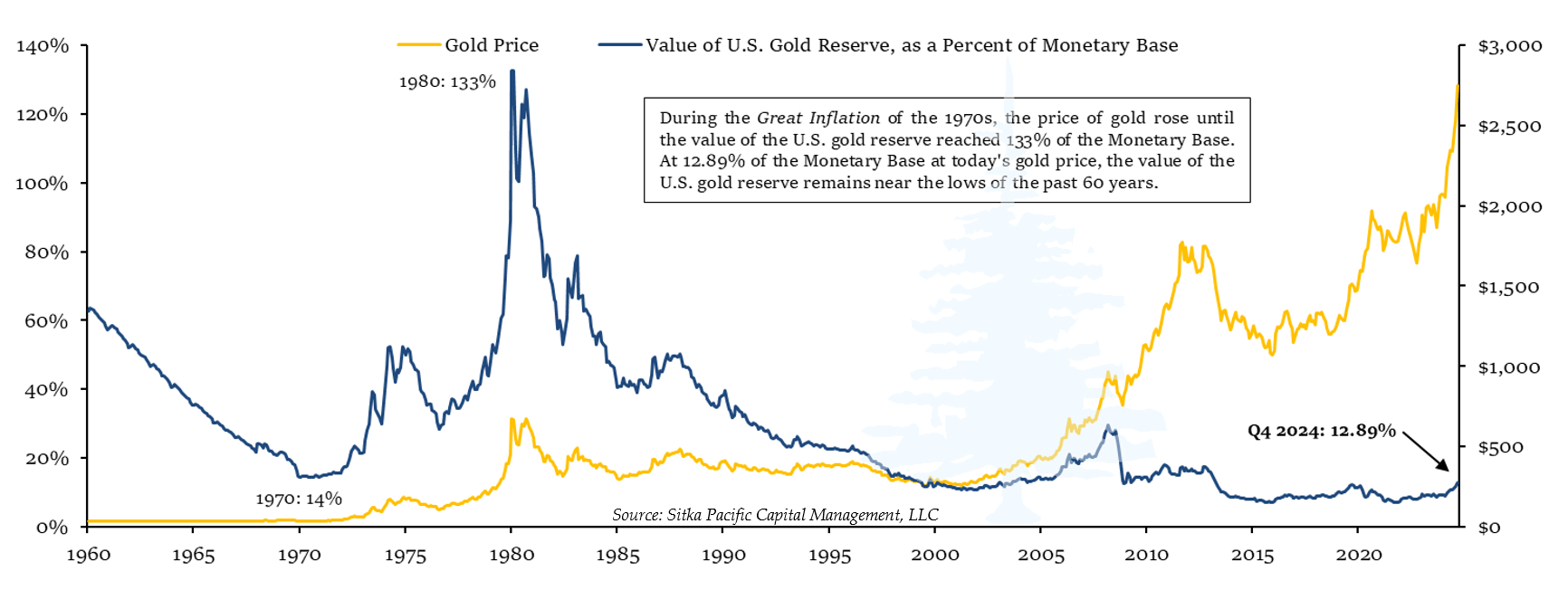

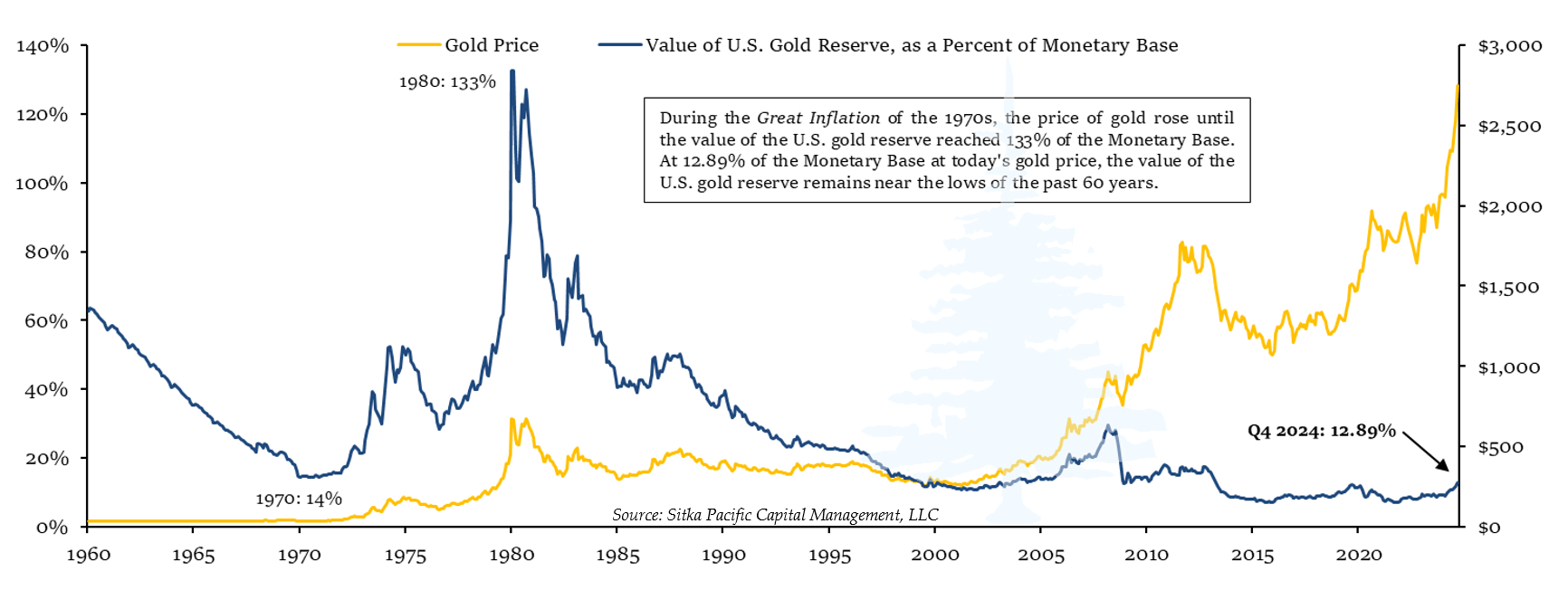

As we have reviewed in recent years, the value of gold backing the U.S. dollar steadily declined throughout the 1960s, and during that time tensions steadily increased between the U.S. and nations holding large dollar reserves. At the height of that tension, the value of the official gold reserve backing the dollar had fallen from 63% in 1960 to just 14%. At that moment in 1970, only 26% of foreign dollar holdings were covered by gold the U.S. held on hand.

The Banque Royale had similarly low reserve levels just before confidence fell apart in 1720. And just as happened back then, the end of U.S. dollar convertibility arrived suddenly, with Nixon’s Sunday evening address to the nation on August 15, 1971, which was evasively titled The Challenge of Peace.

This year, the price of gold has risen strongly, outpacing nearly all major asset classes. In an echo from earlier eras, gold’s rally this year has been fueled mainly by increased demand from large holders of dollars abroad, especially from emerging markets and the People’s Bank of China (PBoC).

Yet as you can see in the chart above, this year’s rise has barely registered relative to monetary aggregates in the U.S. As of the beginning of the 4th quarter, the value of the official U.S. gold reserve remains at just 12.89% of the base money supply. Even after the rise in the past year, gold remains valued near the bottom end of its historic range.

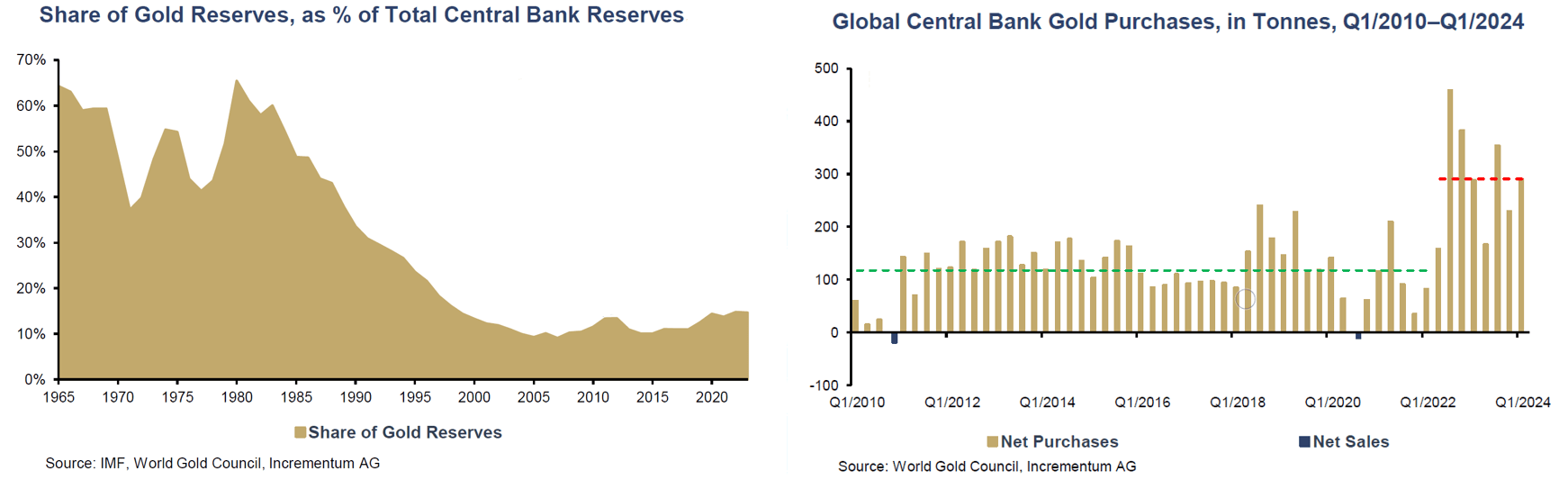

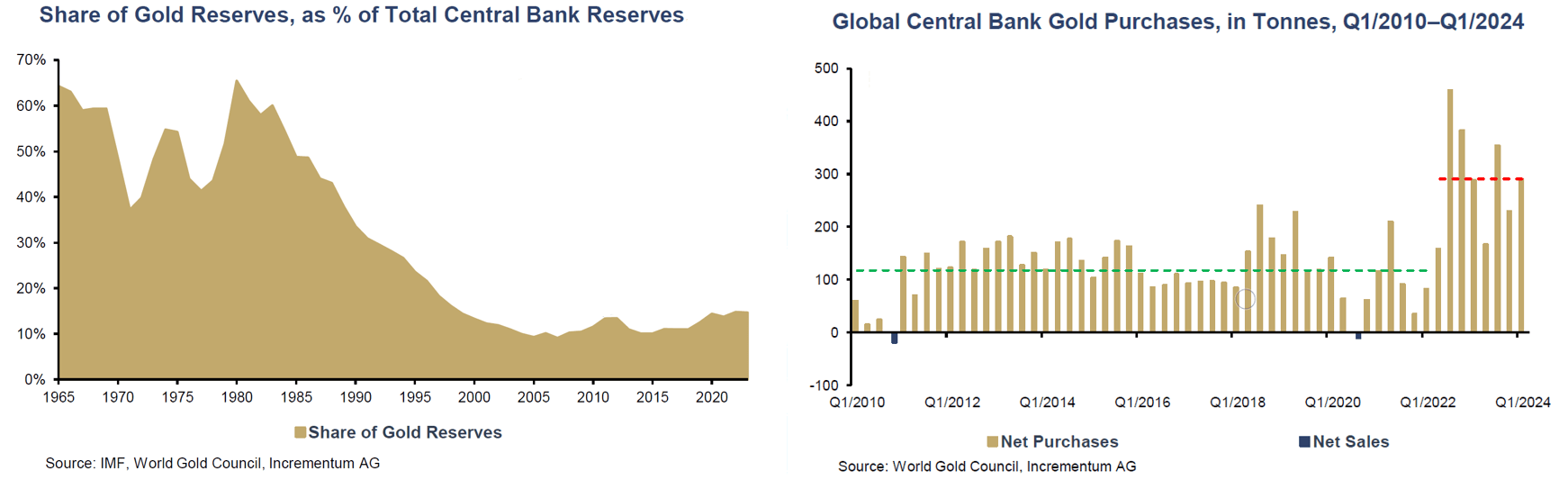

This is the case outside the U.S. as well. Throughout the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, central banks were net sellers of gold, and this resulted in a large decline in the share of central bank reserves held in gold after the early 1980s. Beginning in 2010, central banks reversed and began increasing their gold holdings, as quantitative easing rapidly expanded the money supply. These global central bank purchases accelerated further after Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, and have remained higher ever since.

However, as you can see below, the share of global central bank reserves held in gold remains not far from the lowest levels reached in the past 60 years, even with recently stepped-up purchases.

The main reason central bank purchases over the past decade have not made a meaningful impact on the share of gold backing the world’s currency reserves is simply illustrated by the Federal Reserve. Over the past twenty years, the Fed has expanded the base money supply in the U.S. by 632%. Over the same period, the price of gold has risen 540%. Thus, even with gold’s 10% annualized return over the past two decades, as impressive as it has been, its rising value has lagged the rapid pace of the expanding global money supply.

As a result, the value of gold backing the dollar today remains below where it was on that fateful Sunday when the U.S. gold window closed in August 1971.

In addition to central bank buying, gold’s rally this year has also been fueled by cyclical factors. Throughout 2024, there have been growing signs that the monetary brakes being applied by the Fed were poised to ease off, and as the markets began anticipating this transition toward easing earlier this year, gold began rising. This is in line with how gold responded during previous cycles when the time had come for monetary policy to pivot toward easing.

In summary, from both a value and a cyclical perspective, the market environment for gold has been ideal in 2024, and this ideal environment remains in place as we head into the end of the year. Parts of the yield curve have recently peeked back into positive territory after two years of inversion. Yet this reversion cycle has a long way to go, and the transition from applying the monetary brakes to stepping on the monetary accelerator has historically seen the strongest gold gains.

Yet while this part of the market cycle has historically seen strong gold gains, it has also seen a sharp rise in market volatility. The last four yield curve reversions like we are experiencing today began in 2019, 2007, 2000, and 1990. As you may recall, each of those occurrences was followed by significant downturns in the economy and equity markets. Regardless of each asset classes’ long-term outlook, those downturns caused significant volatility in all asset classes: stocks, bonds, commodities, and precious metals.

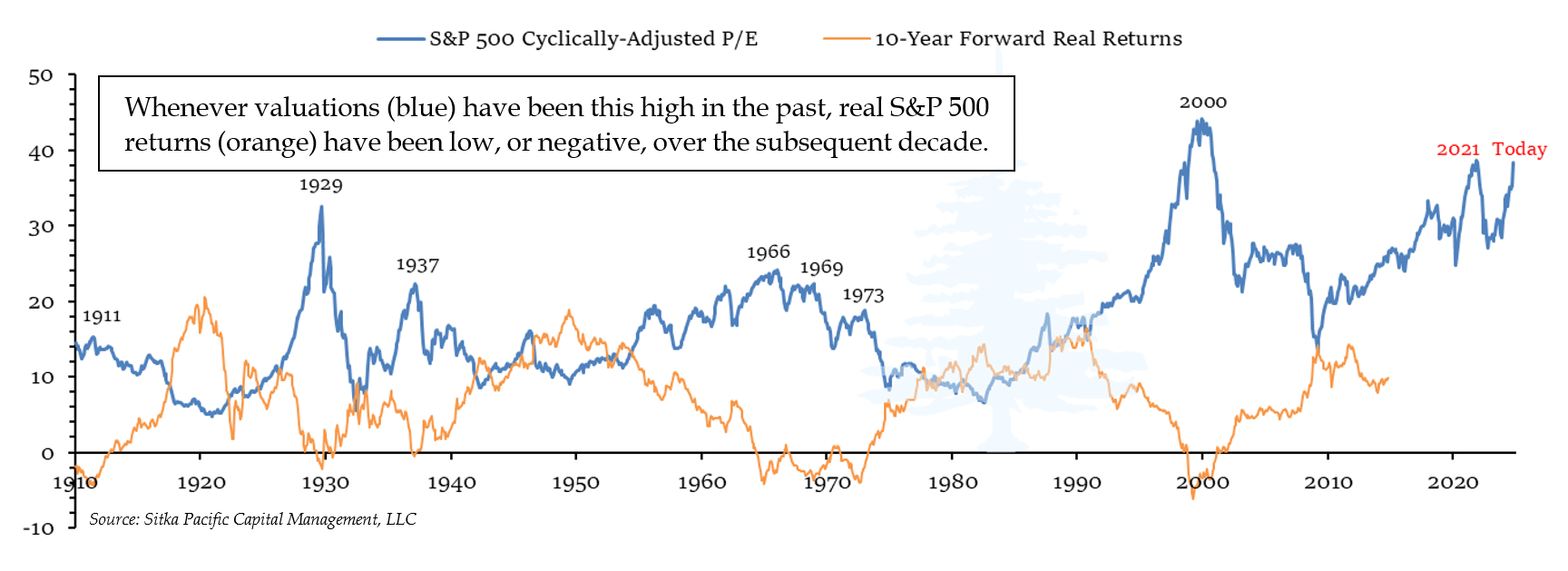

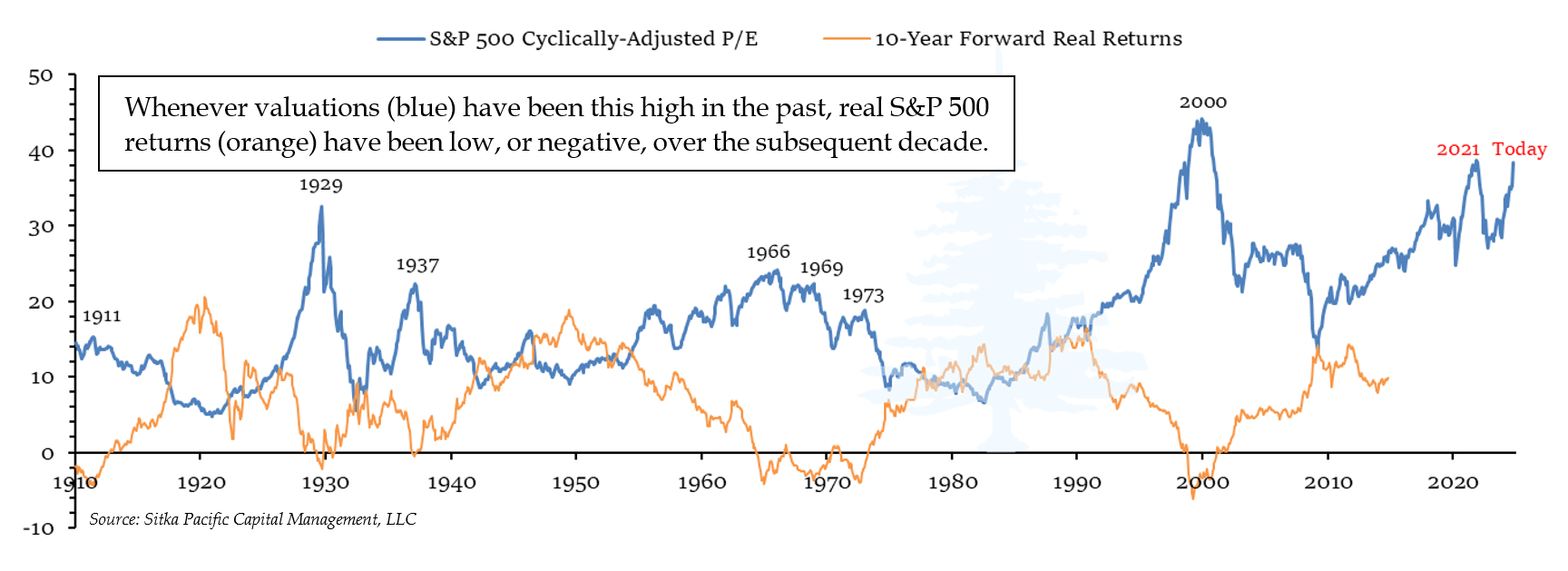

The risk of higher volatility in the year ahead is compounded by sky-high equity market valuations. Unlike many equity markets around the world, the S&P 500 continues to trade at one of the highest valuations in its history. As you can see in the chart below, only the peak in 2000 has recorded a higher cyclically-adjusted price-to-earnings ratio than today’s stratospheric reading of 38.

At the beginning of the third quarter, the S&P 500 achieved another rare valuation milestone: it rose above a price-to-book value of five for the first time since the year 2000. From that record price-to-book at the very peak of the Tech Bubble, a passive investment in the S&P 500 went on to lose a third of its real value over the following decade. Lately here in the 4th quarter, the S&P 500’s price-to-book ratio has risen further to 5.28, exceeding the previous record set in March 2000.

Twenty-four years ago, the valuations we see today marked the beginning of a dismal decade of negative inflation-adjusted returns for the S&P 500. Yet as you can see in the chart above, the negative real returns from the peak of the Tech Bubble are not unique: high valuations have a strong correlation with low, or negative, subsequent real returns going all the way back to the beginning of the last century.

This shows that from both a value perspective and a cyclical perspective, the outlook for the market-capitalization-weighted S&P 500 is, to put it mildly, far less than ideal: investors will be fortunate not to lose real value with a passive S&P 500 investment in the decade ahead.

Fortunately, in the face of the less-than-ideal conditions for the S&P 500 index, 2024 may end up marking the beginning of the long-awaited resurrection of diversification.

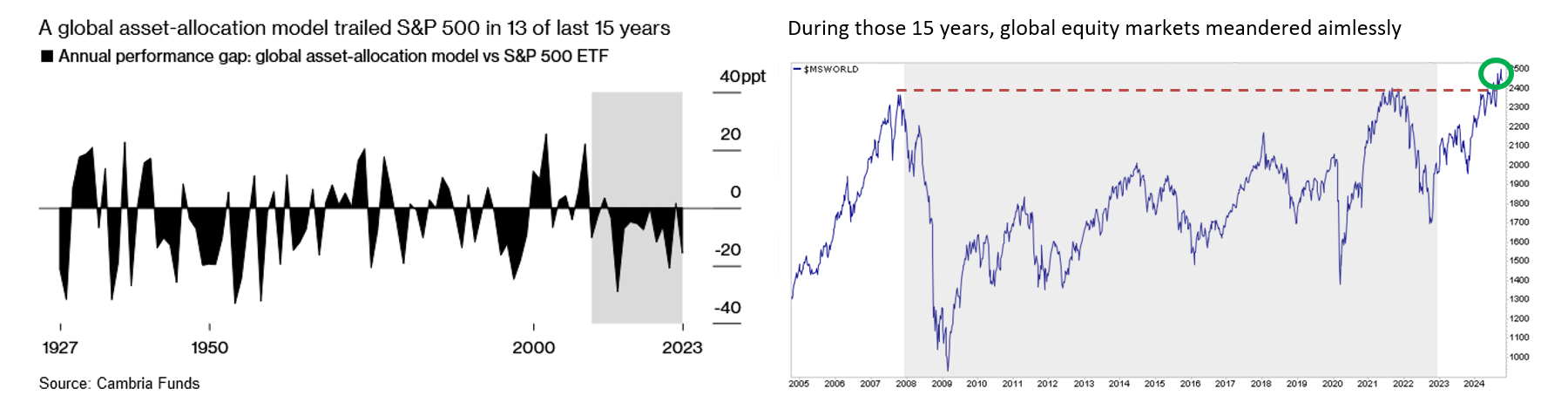

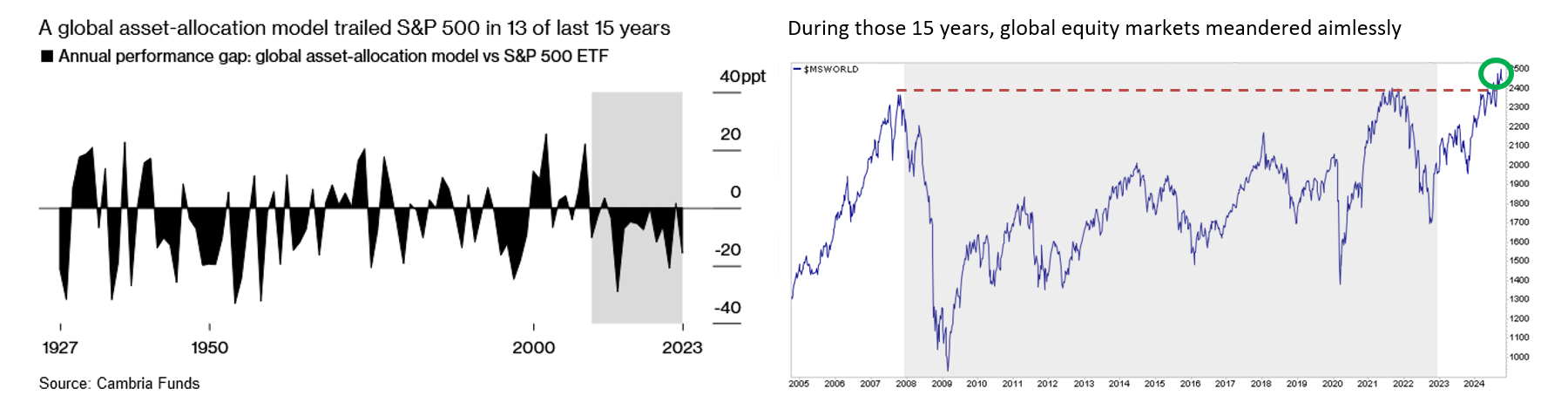

In the years after the financial crisis, diversification – the age-old, time-tested investment approach in which you spread your portfolio across asset classes and regions to reduce risks and increase risk-adjusted returns – entered one of the most severe droughts in modern market history. In 13 of the 15 years after 2008, holding the S&P 500 index alone provided a better return than holding a mix stocks and bonds, or holding a mix of any other asset class outside of U.S. stocks. In fact, the greater degree a portfolio was diversified between 2009 and 2023, the larger the performance gap with large-cap U.S. stocks during those years.

There were five main reasons why diversification outside of U.S. stocks dragged on returns for such a long stretch of time after the financial crisis:

- Zero-percent interest rates snuffed out returns from holding cash.

- In response to entrenched zero-percent interest rates, bond yields were low.

- Commodities broadly deflated after the speculative peak in oil prices in 2008.

- Equity markets outside the U.S. entered an era of contracting valuations.

- U.S. dollar strength dampened low returns on foreign stocks and bonds to below zero.

The combined effect of these trends was that out of 370 diversified asset-allocation funds tracked by Morningstar, only one of them managed to beat the S&P 500 in the years between 2009 and 2023. This under-performance anomaly is highlighted by the grey area in the chart below on the left courtesy of Cambria Funds, which shows the annual performance gap between a diversified approach and the S&P 500. As you can see by the long stretch below zero during that time, diversification has endured a severe drought, the likes of which have not been seen in the past century of data.

The chart on the right highlights how global equity markets traded during that long diversification drought, and also highlights why the drought may be ending.

Holding global equity markets added only volatility and losses to a portfolio after 2008, the impacts of which were amplified by the rise of the dollar. Yet as you can see in the upper right corner, 2024 marked the first year since 2008 that global equity markets rose above their pre-credit-crisis peak to notch a new high. This is a strong sign that after a long 15-year stretch in which global equity markets and their local currencies devalued against the U.S., these undervalued markets are now poised to contribute to returns going forward.

With the return of positive real interest rates, the rise in commodities and precious metals, and the reemergence of global equity markets in 2024, it appears the time has finally come for a new era of more diversified portfolio returns. Although the S&P 500 remains over concentrated, overvalued, and appears poised to deliver negative real returns in the decade ahead, markets and asset classes outside large-cap U.S. stocks appear poised to provide a welcome return of diversification’s benefits.

* * *

Addendum

While we will see in due time how the results of the election affects fiscal policies in the year ahead, at this early stage it seems the net result of any changes from the election will likely provide more stimulus for the economy. If such stimulus is paired with tariffs and other measures that restrict goods and labor supply, the result will be an increase in inflationary pressures. With the Federal debt rising by $2.5 trillion over the past year, with labor costs climbing at a 3.4% pace, and with the Core CPI still rising at a 3.3% rate, the direction of travel for monetary policy may no longer be as clear as Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell thought it was in August.

As we head toward 2025, markets are still adjusting to the return of inflation, and the different set of outcomes higher rates of inflation bring with it. The persistent rise in bond yields we have seen over the past three years, and over the past few months, represents one of those different outcomes. The flow of capital this year to precious metals and equity markets outside the dollar is another.

While there may be significant volatility along the way, these different outcomes are consistent with the progression seen in the histories we have available as a guide – whether that history is from a few centuries ago, or a few decades ago. If those periods are any indication, the market outcomes we have seen this year could continue to supplement and diversify portfolio returns for many years to come.

* * *

The preceding is part of our 4th Quarter letter to clients. To request a copy of the full letter, or to schedule a consultation to review your investments, visit Getting Started.

The content of this article is provided as general information and is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment or other advice. This material is not to be construed as a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any security, financial product, instrument or to participate in any particular trading strategy. Not all securities, products or services described are available in all countries, and nothing herein constitutes an offer or solicitation of any securities, products or services in any jurisdiction where their offer or sale is not qualified or exempt from registration or otherwise legally permissible.

Although the material herein is based upon information considered reliable and up-to-date, Sitka Pacific Capital Management, LLC does not assure that this material is accurate, current, or complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. Content in this article may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted, in whole or in part, without prior written consent — which is usually gladly given, as long as its use includes clear and proper attribution. Contact us for more information.

© Sitka Pacific Capital Management, LLC

The Time Has Finally Come

4th Quarter, 2024

After persisting for as long as two years in the US, the so-called inversion in yield curves — an unusual situation where rates on short-term debt exceed those of their longer-term counterparts — is unwinding in many parts of the world. The normalizing, or steepening, trend first surfaced in July in UK gilts, followed by US Treasuries a month later. Now it is happening in German and Canadian bond markets as well.

The shift is taking place as central banks start to lower benchmark interest rates after years of keeping them elevated…

~ Bloomberg, September 24, 2024

The time has come for policy to adjust. The direction of travel is clear, and the timing and pace of rate cuts will depend on incoming data, the evolving outlook, and the balance of risks.

~ Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, August 23, 2024

* * *

In January 2022, we ventured three hundred years back in time to an episode that has long been considered the classic example of mania in the early annals of market history. The Mississippi Bubble in 1720 is the leading early example of a modern stock market bubble. Although it involved only a single stock, the Company of the West, it remains the most well-documented early episode of public mania, followed by a mass panic and a market crash.

As dramatic as the rise and subsequent collapse was, the primary reason we spent time discussing the Mississippi Bubble was not the boom and bust in Company of the West shares that were traded on the narrow rue Quincampoix. The primary reason, the reason which remains particularly relevant to investors today, was the monetary story underlying the public mania.

If you recall, John Law formed the Banque Royale in Paris so that he could begin issuing paper banknotes. In the beginning, the banknotes were used as receipts for gold and silver coins deposited at the bank, and every circulating banknote represented hard money on deposit.

Law intended that this scheme would solve some very real problems in the French economy. The authentication of coins had been an issue for centuries, and the new paper banknotes were to provide an assurance that the coins represented by the notes had been assayed by the bank and found to contain all the gold and silver they were supposed to. In theory, this would reduce the time, effort, and cost of transactions: those who paid in banknotes, instead of coins, would then be able to trust that the Banque Royale had guaranteed the value of the money they received.

As time went on, however, the Banque Royale undercut that trust by issuing more banknotes than the amount of gold and silver held at the bank – many more banknotes. This excess issuance initially seemed to solve hosts of other problems that had long plagued, and seemingly limited, France’s economy. Capital for projects was no longer so scarce, and citizens throughout France were delighted to realize they suddenly had much more money at their disposal. They initially used this new money to rabidly buy more Company of the West shares, and the lucky early holders of those shares who cashed out began using their newfound wealth to buy homes in Paris, large country estates, and luxury goods of every kind. Prices for those assets then began to soar as well.

The more banknotes the Banque Royale printed and issued to the public, the wealthier everyone seemed to become. It appeared as if the old laws governing economics and money had finally been relegated to the past. Law was credited with unleashing a flood of prosperity onto the citizens of Paris, and the French economy continued to thrive as wealth and spending soared.

When prices began to rise throughout the broader French economy, however, the first cracks appeared in the trust of the very banknotes that had ignited the boom.

It was one thing when asset prices were soaring – that made owners of shares, homes, and land feel immensely wealthy. It was quite another thing when prices for everyday goods began rising. That just made daily life more expensive, and more difficult. It also began sparking questions among the frustrated citizenry – questions about what, exactly, was making the prices of bread, fuel, and feed rise so much.

Amid the early questioning, a handful of wealthy citizens reached their own conclusions in late 1719, and stealthily began exchanging their banknotes back to gold. The only problem was, by that time there was only enough gold in the Banque Royale to redeem a small fraction of the notes in circulation. As the early trickle out of banknotes turned into a run in 1720, gold’s price began to rise.

* * *

While a narrative from three centuries ago may seem like ancient history, it was not too long ago that a similar progression unfolded in the U.S., for reasons similar to those in France in 1720.

As we have reviewed in recent years, the value of gold backing the U.S. dollar steadily declined throughout the 1960s, and during that time tensions steadily increased between the U.S. and nations holding large dollar reserves. At the height of that tension, the value of the official gold reserve backing the dollar had fallen from 63% in 1960 to just 14%. At that moment in 1970, only 26% of foreign dollar holdings were covered by gold the U.S. held on hand.

The Banque Royale had similarly low reserve levels just before confidence fell apart in 1720. And just as happened back then, the end of U.S. dollar convertibility arrived suddenly, with Nixon’s Sunday evening address to the nation on August 15, 1971, which was evasively titled The Challenge of Peace.

This year, the price of gold has risen strongly, outpacing nearly all major asset classes. In an echo from earlier eras, gold’s rally this year has been fueled mainly by increased demand from large holders of dollars abroad, especially from emerging markets and the People’s Bank of China (PBoC).

Yet as you can see in the chart above, this year’s rise has barely registered relative to monetary aggregates in the U.S. As of the beginning of the 4th quarter, the value of the official U.S. gold reserve remains at just 12.89% of the base money supply. Even after the rise in the past year, gold remains valued near the bottom end of its historic range.

This is the case outside the U.S. as well. Throughout the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, central banks were net sellers of gold, and this resulted in a large decline in the share of central bank reserves held in gold after the early 1980s. Beginning in 2010, central banks reversed and began increasing their gold holdings, as quantitative easing rapidly expanded the money supply. These global central bank purchases accelerated further after Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, and have remained higher ever since.

However, as you can see below, the share of global central bank reserves held in gold remains not far from the lowest levels reached in the past 60 years, even with recently stepped-up purchases.

The main reason central bank purchases over the past decade have not made a meaningful impact on the share of gold backing the world’s currency reserves is simply illustrated by the Federal Reserve. Over the past twenty years, the Fed has expanded the base money supply in the U.S. by 632%. Over the same period, the price of gold has risen 540%. Thus, even with gold’s 10% annualized return over the past two decades, as impressive as it has been, its rising value has lagged the rapid pace of the expanding global money supply.

As a result, the value of gold backing the dollar today remains below where it was on that fateful Sunday when the U.S. gold window closed in August 1971.

In addition to central bank buying, gold’s rally this year has also been fueled by cyclical factors. Throughout 2024, there have been growing signs that the monetary brakes being applied by the Fed were poised to ease off, and as the markets began anticipating this transition toward easing earlier this year, gold began rising. This is in line with how gold responded during previous cycles when the time had come for monetary policy to pivot toward easing.

In summary, from both a value and a cyclical perspective, the market environment for gold has been ideal in 2024, and this ideal environment remains in place as we head into the end of the year. Parts of the yield curve have recently peeked back into positive territory after two years of inversion. Yet this reversion cycle has a long way to go, and the transition from applying the monetary brakes to stepping on the monetary accelerator has historically seen the strongest gold gains.

Yet while this part of the market cycle has historically seen strong gold gains, it has also seen a sharp rise in market volatility. The last four yield curve reversions like we are experiencing today began in 2019, 2007, 2000, and 1990. As you may recall, each of those occurrences was followed by significant downturns in the economy and equity markets. Regardless of each asset classes’ long-term outlook, those downturns caused significant volatility in all asset classes: stocks, bonds, commodities, and precious metals.

The risk of higher volatility in the year ahead is compounded by sky-high equity market valuations. Unlike many equity markets around the world, the S&P 500 continues to trade at one of the highest valuations in its history. As you can see in the chart below, only the peak in 2000 has recorded a higher cyclically-adjusted price-to-earnings ratio than today’s stratospheric reading of 38.

At the beginning of the third quarter, the S&P 500 achieved another rare valuation milestone: it rose above a price-to-book value of five for the first time since the year 2000. From that record price-to-book at the very peak of the Tech Bubble, a passive investment in the S&P 500 went on to lose a third of its real value over the following decade. Lately here in the 4th quarter, the S&P 500’s price-to-book ratio has risen further to 5.28, exceeding the previous record set in March 2000.

Twenty-four years ago, the valuations we see today marked the beginning of a dismal decade of negative inflation-adjusted returns for the S&P 500. Yet as you can see in the chart above, the negative real returns from the peak of the Tech Bubble are not unique: high valuations have a strong correlation with low, or negative, subsequent real returns going all the way back to the beginning of the last century.

This shows that from both a value perspective and a cyclical perspective, the outlook for the market-capitalization-weighted S&P 500 is, to put it mildly, far less than ideal: investors will be fortunate not to lose real value with a passive S&P 500 investment in the decade ahead.

Fortunately, in the face of the less-than-ideal conditions for the S&P 500 index, 2024 may end up marking the beginning of the long-awaited resurrection of diversification.

In the years after the financial crisis, diversification – the age-old, time-tested investment approach in which you spread your portfolio across asset classes and regions to reduce risks and increase risk-adjusted returns – entered one of the most severe droughts in modern market history. In 13 of the 15 years after 2008, holding the S&P 500 index alone provided a better return than holding a mix stocks and bonds, or holding a mix of any other asset class outside of U.S. stocks. In fact, the greater degree a portfolio was diversified between 2009 and 2023, the larger the performance gap with large-cap U.S. stocks during those years.

There were five main reasons why diversification outside of U.S. stocks dragged on returns for such a long stretch of time after the financial crisis:

- Zero-percent interest rates snuffed out returns from holding cash.

- In response to entrenched zero-percent interest rates, bond yields were low.

- Commodities broadly deflated after the speculative peak in oil prices in 2008.

- Equity markets outside the U.S. entered an era of contracting valuations.

- U.S. dollar strength dampened low returns on foreign stocks and bonds to below zero.

The combined effect of these trends was that out of 370 diversified asset-allocation funds tracked by Morningstar, only one of them managed to beat the S&P 500 in the years between 2009 and 2023. This under-performance anomaly is highlighted by the grey area in the chart below on the left courtesy of Cambria Funds, which shows the annual performance gap between a diversified approach and the S&P 500. As you can see by the long stretch below zero during that time, diversification has endured a severe drought, the likes of which have not been seen in the past century of data.

The chart on the right highlights how global equity markets traded during that long diversification drought, and also highlights why the drought may be ending.

Holding global equity markets added only volatility and losses to a portfolio after 2008, the impacts of which were amplified by the rise of the dollar. Yet as you can see in the upper right corner, 2024 marked the first year since 2008 that global equity markets rose above their pre-credit-crisis peak to notch a new high. This is a strong sign that after a long 15-year stretch in which global equity markets and their local currencies devalued against the U.S., these undervalued markets are now poised to contribute to returns going forward.

With the return of positive real interest rates, the rise in commodities and precious metals, and the reemergence of global equity markets in 2024, it appears the time has finally come for a new era of more diversified portfolio returns. Although the S&P 500 remains over concentrated, overvalued, and appears poised to deliver negative real returns in the decade ahead, markets and asset classes outside large-cap U.S. stocks appear poised to provide a welcome return of diversification’s benefits.

* * *

Addendum

While we will see in due time how the results of the election affects fiscal policies in the year ahead, at this early stage it seems the net result of any changes from the election will likely provide more stimulus for the economy. If such stimulus is paired with tariffs and other measures that restrict goods and labor supply, the result will be an increase in inflationary pressures. With the Federal debt rising by $2.5 trillion over the past year, with labor costs climbing at a 3.4% pace, and with the Core CPI still rising at a 3.3% rate, the direction of travel for monetary policy may no longer be as clear as Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell thought it was in August.

As we head toward 2025, markets are still adjusting to the return of inflation, and the different set of outcomes higher rates of inflation bring with it. The persistent rise in bond yields we have seen over the past three years, and over the past few months, represents one of those different outcomes. The flow of capital this year to precious metals and equity markets outside the dollar is another.

While there may be significant volatility along the way, these different outcomes are consistent with the progression seen in the histories we have available as a guide – whether that history is from a few centuries ago, or a few decades ago. If those periods are any indication, the market outcomes we have seen this year could continue to supplement and diversify portfolio returns for many years to come.

* * *

The preceding is part of our 4th Quarter letter to clients. To request a copy of the full letter, or to schedule a consultation to review your investments, visit Getting Started.

The content of this article is provided as general information and is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment or other advice. This material is not to be construed as a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any security, financial product, instrument or to participate in any particular trading strategy. Not all securities, products or services described are available in all countries, and nothing herein constitutes an offer or solicitation of any securities, products or services in any jurisdiction where their offer or sale is not qualified or exempt from registration or otherwise legally permissible.

Although the material herein is based upon information considered reliable and up-to-date, Sitka Pacific Capital Management, LLC does not assure that this material is accurate, current, or complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. Content in this article may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted, in whole or in part, without prior written consent — which is usually gladly given, as long as its use includes clear and proper attribution. Contact us for more information.

© Sitka Pacific Capital Management, LLC

Investment Management

Before investing, we will discuss your goals and risk tolerances with you to see if a separately managed account at Sitka Pacific would be a good fit. To contact us for a free consultation, visit Getting Started.

Macro Value Monitor

To read a selection of recent client letters and be alerted when new letters are posted to our public site, visit Recent Client Letters.