The Moment When Monetary Policy Runs Aground on the Third Great Mistake

March 2, 2022

The U.S. national debt exceeded $30 trillion for the first time, reflecting increased federal borrowing during the coronavirus pandemic. Total public debt outstanding was $30.01 trillion as of Jan. 31, according to Treasury Department data released Tuesday. That was a nearly $7 trillion increase from late January 2020, just before the pandemic hit the U.S. economy.

The debt milestone comes at a time of transition for U.S. fiscal and monetary policy, which will likely have implications for the broader economy. Many of the federal pandemic aid programs authorized by Congress have expired, leaving Americans with less financial assistance than earlier in the pandemic. Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve has signaled it could soon begin to raise short-term interest rates from near zero in an effort to curb inflation, which is at its highest level in nearly four decades.

-The Wall Street Journal, February 1, 2022

The Fed can change how things look; it cannot change what things are.

-Jim Grant

The story of the Banque Royale and the Mississippi Bubble in the first issue of The Macro Value Monitor may sound like a tall tale of financial fiction, but those events did in fact occur three centuries ago in France. There is nothing fictional about the impact of quantitative easing on financial markets, or on those attempting to navigate them.

The flood of banknotes out of the Banque Royale and into the streets of Paris in 1719 ushered in a speculative fervor so alluring that it fundamentally altered the behavior of even the most conservative members of society. Many of those who had been content for decades to earn stable income from their estates, their positions or their trade suddenly found themselves feeling left behind by the rapidly inflating wealth of the Company of the West shareholders. Many panicked and scrambled for a way to catch up, before it was too late.

By early 1720, it seemed the only way to keep up was to hold on tightly to as many Company of the West shares as one could get one’s hands on. Whereas before the Banque Royale the path to private wealth had been through privileged inheritance, trade, business or industry, the flood of banknotes made aggressive, speculative wagers seem like the only way to prosperity — regardless of what the shares changing hands on rue Quincampoix actually represented. When the money supply is rapidly expanding, the old ways of wealth accumulation and preservation suddenly seem hopelessly out of date, and they are eventually abandoned amid desperate attempts to avoid missing out on the new path to wealth.

Lost in the frenzy for Company of the West shares was the fact that only 500 European settlers inhabited the entire Mississippi territory, which remained profitless and undeveloped, save for a few struggling villages. Hunger was rampant. Yet this was the primary asset behind an enterprise valued as much as the entire national product of France at its peak.

The real impetus behind the explosive money supply expansion in late 1719 that fueled the rise of Company of the West shares was more or less the same as it has been with the expansion of the money supply in this 21st century — unsustainable debt. When the regent faced the unpalatable choice between raising taxes, cutting spending or defaulting on debts to the nobility in 1715, Law’s system of reserved, and then fractionally reserved, banknotes offered an easier way out. It preserved the peace among all the social classes, and, most importantly, it preserved the moral authority of the monarchy.

Yet it also set in motion a chain of events that eventually precipitated the end of confidence in the livre itself, as well as liquid assets denominated in livres. While Law clearly saw the untapped potential that could be unleashed if the French economy had a more efficient monetary system, and the immense profit that could be realized in the long run with the development of the Mississippi territory, he failed to see some of the other effects the end of monetary restraint would have. In other words, there were unintended consequences that Law didn’t foresee — and those consequences turned his entire endeavor into a Great Mistake.

Great Mistakes have plagued modern monetary policy as well. Among historians, there have been two Great Mistakes in Federal Reserve history, and the lessons from those periods continue to echo through the halls of the Eccles building in Washington, D.C. to this day. A full understanding of what is driving monetary policy decisions today is not possible without understanding the Fed’s earlier mistakes, and understanding those periods is essential to understanding the Fed’s current predicament.

The first Great Mistake in the history of the Federal Reserve occurred during the first two years of the Great Depression. In its failure to understand the catastrophic nature of the credit collapse in the early 1930s as it unfolded, and in its failure to appreciate the difference between nominal interest rates and real, inflation-(or deflation)-adjusted interest rates, the Federal Reserve unwittingly allowed monetary policy to dramatically tighten as the economic contraction deepened after 1930. Yet as that policy tightening took hold, nearly all Fed governors at the time assumed monetary policy was “loose.”

As prices throughout the economy began to fall, the Fed held its policy rate near the lowest level in its short history, leading most Fed governors to assume they had eased monetary policy enough. This sentiment was prevalent, in part, because the Fed had eased policy aggressively during the 1926–1927 recession, which turned out to be only a mild contraction. As a result, financial markets had boomed when the recession ended. In 1930, a number of Fed governors thought the markets and the economy needed to “correct” a good portion of the “excesses” seen in 1928 and 1929.

However, as the decline in prices eventually accelerated to a 10% annual rate in 1932, real interest rates rose as high as 12%. These high real, deflation-adjusted interest rates rapidly accelerated the contraction of credit, and helped turn the recession of 1930 into the Great Depression of the 1930s. The Federal Reserve has been haunted ever since by its inaction.

In a 2002 speech at a conference honoring the economist Milton Freedman, then-Fed Governor Ben Bernanke publicly apologized for this policy mistake on behalf of the Federal Reserve, telling his audience: “Regarding the Great Depression, … we did it. We’re very sorry. … We won’t do it again.” Little did Bernanke know as he spoke those words, he would personally be given the opportunity to put the main lessons learned from the Fed’s first Great Mistake into action just six years later, when the credit crisis hit in 2008.

The second Great Mistake in the history of the Federal Reserve was the set of events and policies that resulted in the Great Inflation of the 1970s. With the Great Depression still haunting the meetings of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), Fed governors were hypervigilant in monitoring for any signs of a contraction in credit and prices during the 1960s and early 1970s. Yet, in a mistake quite similar to their oversight during the first few years of the Great Depression, Fed officials continued to ignore real, inflation-adjusted interest rates. In addition, they also knowingly allowed political pressure pushing for easier monetary policy to impact their decision making.

As prices throughout the economy began to rise at faster rates beginning in the mid-1960s, the full weight of presidents Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon bore down on Fed chairmen McChesney Martin and Arthur Burns.

That Executive pressure poignantly began when President Johnson summoned Chairman Martin to Texas on December 6th, 1965. Johnson was incensed that the Fed had raised interest rates at its meeting on December 3rd, and he aggressively confronted Martin when he arrived as his ranch. In one of the most infamous encounters in Federal Reserve history, Johnson pressed Martin up against the wall in his living room and lambasted Martin for raising interest rates without his approval. He forcefully told Martin:

“You went ahead and did something that you knew I disapproved of, that can affect my entire term here. You took advantage of me and I’m not going to forget it.… You’ve got me into a position where you can run a rapier into me and you’ve run it. Martin, my boys are dying in Vietnam, and you won’t print the money I need.”

– President Lynden Johnson to Fed Chairman McChesney Martin, December 3, 1965

From that moment onward, real, inflation-adjusted interest rates pivoted to a downward trajectory, which continued through the Nixon presidency.

Nixon had lost the presidential election in 1960, he firmly believed, because unemployment had risen just prior to voting time. As a result, when he finally reached the presidency he relentlessly pushed policies that would counter any potential rise in unemployment. During this era in economic thinking, an unacceptable unemployment rate was considered anything above 4% — what the economic models of the time said was the full employment rate. In the relentless drive to keep the economy near full employment, the Federal Reserve, under pressure from the Executive Branch, ended monetary tightening campaigns early and reverted to expansionary policies whenever unemployment rose above 4%. This easy-policy approach played a large role in accelerating the inflation of prices through the 1970s.

Nixon also had a simpler and more pragmatic view of Federal Reserve independence than his predecessors did. When he installed Arthur Burns as chairman of the Fed in 1970, he succinctly summarized his opinion of his new Fed chairman:

“I respect his independence. However, I hope that independently he will conclude that my views are the ones he should follow.“

– President Richard Nixon on new Fed Chairman Arthur Burns, 1970

In wake of the 1970s Great Inflation, the Federal Reserve became hypervigilant in watching for both a contraction in credit and an unwanted acceleration in prices, all while maintaining a very public posture of independence from the rest of the federal government. These three priorities — avoiding a contraction in credit, avoiding an uncontrollable rise in prices, and maintaining independence from the rest of the federal government — reflect difficult lessons-learned from the first two Great Mistakes in Federal Reserve history.

Yet this hypervigilance for any sign of credit distress, or any incipient inflation, resulted in policy actions over the following decades that repeatedly sought to stabilize any disturbance, large or small. Whether it be a stock market crash, as in 1987, distress from an overleveraged hedge fund, as in the case of Long-Term Capital Management in 1998, or the fear of a potential rise in inflation above target, as was the case in 2016, the Fed remained vigilant in containing any potential credit or inflation risk. And by maintaining that hypervigilance, the Federal Reserve has unwittingly walked into a Third Great Mistake: the loss of control over monetary policy due to the buildup of debt.

As the economy, financial markets and government became increasingly accustomed to being bailed out in the event of any turbulence, leverage and debt soared to unprecedented post-war heights. The Greenspan Put became the Bernanke Put, and investors and borrowers came to understand all too well that the Federal Reserve would forcefully counter any downside deviation in the economy and financial markets.

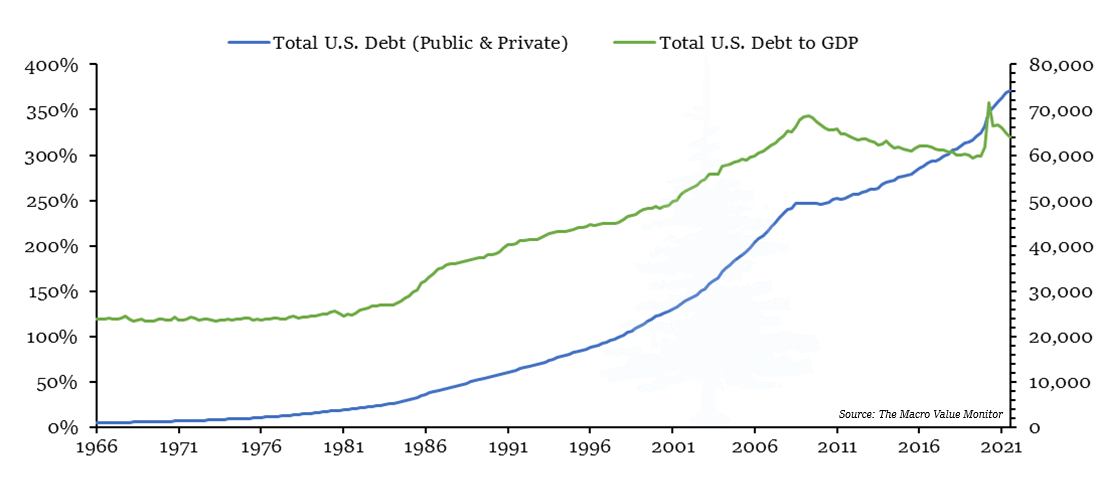

Yet as debt and leverage increased, so did the fragility and sensitivity of the financial markets, resulting in a growing Catch 22 for monetary policy: increasing debt demanded increasingly aggressive monetary responses to downturns, which encouraged even higher indebtedness. And since the financial crisis in 2008, monetary policy has carefully operated at the mercy of this elevated leverage and debt, which has remained above 300% of U.S. GDP since 2005.

The latest full figures show total U.S. debt at $74.177 trillion as of the second quarter of 2021, which represented 320% of GDP. More than a third of that is represented by the federal government’s debt, which rose above $30 trillion just a few weeks ago, on January 31st. The federal debt has climbed more than $7 trillion just over the past two years, and this enormous obligation places an equally enormous political burden on monetary policy, the likes of which has not been seen since the days of Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon.

* * *

In his most recent press conference on January 26th, current Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell sought to prepare the markets for the end of zero-percent short-term interest rates, as well as the end of the pandemic-induced purchasing of Treasury and mortgage-backed securities. With inflation proving far more durable and widespread than the Fed thought remotely possible just a year ago, Powell made it clear it was time for the highly accommodative stance of U.S. monetary policy over the past two years to end.

To a question at his press conference about how fast interest rates may begin to rise, Powell offered this response:

We know that the economy is in a very different place than it was when we began raising rates in 2015. Specifically, the economy is now much stronger. The labor market is far stronger. Inflation is running well above our 2 percent target, much higher than it was at that time. And these differences are likely to have important implications for the appropriate pace of policy adjustments…

I think there’s quite a bit of room to raise interest rates without threatening the labor market. This is, by so many measures, a historically tight labor market, record levels of job openings, of quits. Wages are moving up at the highest pace they have in decades. If you look at surveys of workers, they find jobs plentiful. Look at surveys of companies, they find workers scarce. And all of those readings are at levels really that we haven’t seen in a long time and, in some cases, ever. So, this is a very, very strong labor market. And my strong sense is that we can move rates up without having to, you know, severely undermine it.

It is important to remember that the Federal Reserve views its public comments, such as those above, as one of the most important tools it has available to achieve the goals of its dual mandate. So, when the chair of the Federal Reserve makes it clear he views the labor market as historically tight, that is an unambiguous message to the markets that monetary policy is about to pivot away from supporting the employment recovery to focusing on inflation. Even though total employment in the U.S. remains 2.875 million jobs below where it was two years ago in February 2020, just before the pandemic lockdowns began, from a monetary policy perspective, the Fed now views the employment side of its dual mandate as having been achieved.

It is also important to remember that the policies of the Federal Reserve almost always follow the financial markets, and it is clear the markets have been slowly pricing in the end of the most aggressive monetary response in Federal Reserve history over the past year.

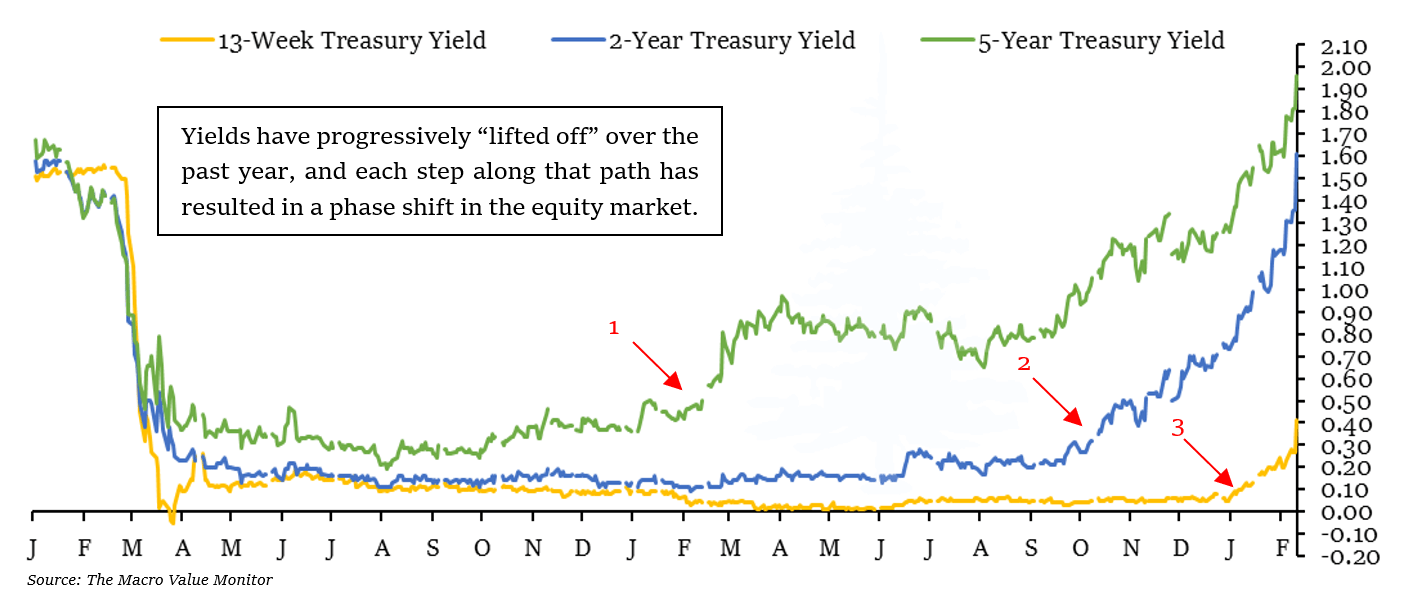

While the Federal Funds rate appears poised to “lift off” from zero in March, yields throughout the yield curve have been lifting off since late 2020. Longer-term Treasury yields began rising from their ultra-low levels in October 2020, and since then the lift-off in yields has moved progressively down the yield curve toward shorter maturities: the 5-Year Treasury yield began rising in February 2021; the 2-Year Treasury yield began rising in October 2021; and the 3-Month (13-Week) Treasury yield began rising in January of this year. And each successive pivot higher along the yield curve corresponded with an equally significant technical pivot in the equity market.

When the 5-Year Treasury yield pivoted higher in February 2021, as noted by the #1 on the chart above, it marked the climax of the meme-stock frenzy, and the massive short-squeezes it fomented in stocks like GameStop. It also marked the peak of the most speculative tech names, such as those which have been the focus of Cathy Woods’ ARKK fund, which has fallen 64% from its peak a year ago. When the 2-Year Treasury began rising last October, as noted by the #2 in the chart, it marked the peak of the broader Nasdaq indexes, which have since fallen more than 15%. The small-cap Russell 2000 reached its highest point the following month. And when the 13-Week Treasury yield began rising at the beginning of January, as noted by #3, the broader equity market began to decline.

These significant interest rate pivots, coincident with the progressive erosion of breadth in the equity market, unfolded in plain sight. It is a textbook example of what the peak of a major market bubble looks like, as the peaks in 1929 and 2000 unfolded in an almost identical progression.

However, the erosion over the past year was all the more remarkable since quantitative easing continued throughout the entire progression: everything that has been seen up to this point in the markets has been with the Federal Reserve still buying tens of billions of Treasury and mortgage-backed bonds every month. We have yet to see how the markets will function without that monetary support, let alone with an increasing Federal Funds rate, or a shrinking Fed balance sheet. That market environment lies ahead.

In his press conference, Powell also made it clear that the Fed, in addition to raising interest rates, intends to eventually begin shrinking its balance sheet after the end of its current quantitative easing programs:

Asset purchases were enormously important at the beginning of the recovery in terms of restoring market function as they were at — right after the — in the critical phase of the global financial crisis. And then, after, they were a macroeconomic tool to support demand. And now the economy no longer needs this highly accommodative policy that we put in place. So it’s time to stop asset purchases first and then, at the appropriate time, start to shrink the balance sheet.

Now, the balance sheet is substantially larger than it needs to be. We’ve identified the end state as — in amounts needed to implement monetary policy efficiently, effectively in the ample reserve regime. So there’s a substantial amount of shrinkage in the balance sheet to be done. That’s going to take some time.

We want that process to be orderly and predictable … [but] I don’t think it’s possible to say exactly how this is going to go. And we’re going to need to be, as I’ve mentioned, nimble about this…

* * *

In the spring of 1720, John Law began to understand the perilous monetary situation France was in, as the Banque Royale continued to rapidly expand the money supply. Although Company of the West shares remained aloft, which encouraged citizens to exchange their debt holdings for shares, there were clear signs that confidence in banknotes was beginning to falter: prices throughout France had begun to rise, including the price of gold and silver, despite all the legal prohibitions.

Although Law desperately needed Company of the West shares to remain high until he could complete the exchange of shares for the king’s debt, it dawned on him that if confidence in banknotes cracked, his entire endeavor to remake France’s monetary system and spur the development of the Mississippi territory would quickly unravel. In a desperate attempt to maintain confidence, Law decided in May 1720 to shrink the supply of banknotes back down to his estimate of the total value of real assets in France. In the end, however, the attempt to restore monetary balance only accelerated the collapse, as the general public, unaware until then how little backed their banknotes, suddenly panicked and rushed for the exit.

In the aftermath of the Mississippi Bubble, the statutory value of the livre was returned to a specific amount of gold and silver, and over the following decade, many of the debts which had been exchanged for then-worthless Company of the West shares were restored to their former value. The gold and silver contract clauses that had been voided were reinstated, and the courts spent years working through the remittances on a case-by-case basis. These actions reestablished a stable monetary order, which remained in place until the French Revolution seventy years later. The Great Mistake of Law’s Banque Royale was over.

In the months and years ahead, we are going to see if Chair Powell and the Federal Reserve will be able to do what John Law failed to accomplish: restore monetary balance before confidence in the dollar erodes and inflation takes root. The Fed now appears to be aware that a base money supply of $9 trillion is not without risks, either in the form of generating significant inflation, or in terms of encouraging a new inflationary psychology — i.e. an erosion of confidence in the dollar — taking root in the broader public. The Fed has now sent clear signals that interest rates are about to rise, and the base money supply is about to shrink.

The big question is how much headway the Fed will ultimately make toward achieving these goals before its effort to confront rising prices runs aground on the $74 trillion in debt in the U.S. economy, over $30 trillion of which is the obligation of the federal government. As John Law discovered, despite the logic of his plan to restore monetary balance, events ultimately spiraled out of his control. The Federal Reserve similarly lost control during its first two Great Mistakes. While it is clear Chair Powell and other Fed officials see what must be done in order to avoid a long-term erosion of confidence in the dollar, it is not so clear they see the pressures that will come to bear in doing so.

* * *

The above is part 1 of Volume I Issue II of The Macro Value Monitor, a publication that focuses on Monetary History, Market Myths, Investing Legends, and Real Global Value. Part 2 of February’s issue, The End of Ultra-Low Yields and the Standard 60/40 Portfolio, is available here.

Return to Recent Memos, Articles and Letters

The content of this document is provided as general information and is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment or other advice. This material is not to be construed as a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any security, financial product, instrument or to participate in any particular trading strategy. Not all securities, products or services described are available in all countries, and nothing herein constitutes an offer or solicitation of any securities, products or services in any jurisdiction where their offer or sale is not qualified or exempt from registration or otherwise legally permissible.

Although the material herein is based upon information considered reliable and up-to-date, Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC does not assure that this material is accurate, current, or complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. Content in this document may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted, in whole or in part, without prior written consent from Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC — which is usually gladly given, as long as its use includes clear and proper attribution. Contact us for more information.

© Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC

The Moment When Monetary Policy Runs Aground on the Third Great Mistake

March 2, 2022

The U.S. national debt exceeded $30 trillion for the first time, reflecting increased federal borrowing during the coronavirus pandemic. Total public debt outstanding was $30.01 trillion as of Jan. 31, according to Treasury Department data released Tuesday. That was a nearly $7 trillion increase from late January 2020, just before the pandemic hit the U.S. economy.

The debt milestone comes at a time of transition for U.S. fiscal and monetary policy, which will likely have implications for the broader economy. Many of the federal pandemic aid programs authorized by Congress have expired, leaving Americans with less financial assistance than earlier in the pandemic. Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve has signaled it could soon begin to raise short-term interest rates from near zero in an effort to curb inflation, which is at its highest level in nearly four decades.

-The Wall Street Journal, February 1, 2022

The Fed can change how things look; it cannot change what things are.

-Jim Grant

The story of the Banque Royale and the Mississippi Bubble in the first issue of The Macro Value Monitor may sound like a tall tale of financial fiction, but those events did in fact occur three centuries ago in France. There is nothing fictional about the impact of quantitative easing on financial markets, or on those attempting to navigate them.

The flood of banknotes out of the Banque Royale and into the streets of Paris in 1719 ushered in a speculative fervor so alluring that it fundamentally altered the behavior of even the most conservative members of society. Many of those who had been content for decades to earn stable income from their estates, their positions or their trade suddenly found themselves feeling left behind by the rapidly inflating wealth of the Company of the West shareholders. Many panicked and scrambled for a way to catch up, before it was too late.

By early 1720, it seemed the only way to keep up was to hold on tightly to as many Company of the West shares as one could get one’s hands on. Whereas before the Banque Royale the path to private wealth had been through privileged inheritance, trade, business or industry, the flood of banknotes made aggressive, speculative wagers seem like the only way to prosperity — regardless of what the shares changing hands on rue Quincampoix actually represented. When the money supply is rapidly expanding, the old ways of wealth accumulation and preservation suddenly seem hopelessly out of date, and they are eventually abandoned amid desperate attempts to avoid missing out on the new path to wealth.

Lost in the frenzy for Company of the West shares was the fact that only 500 European settlers inhabited the entire Mississippi territory, which remained profitless and undeveloped, save for a few struggling villages. Hunger was rampant. Yet this was the primary asset behind an enterprise valued as much as the entire national product of France at its peak.

The real impetus behind the explosive money supply expansion in late 1719 that fueled the rise of Company of the West shares was more or less the same as it has been with the expansion of the money supply in this 21st century — unsustainable debt. When the regent faced the unpalatable choice between raising taxes, cutting spending or defaulting on debts to the nobility in 1715, Law’s system of reserved, and then fractionally reserved, banknotes offered an easier way out. It preserved the peace among all the social classes, and, most importantly, it preserved the moral authority of the monarchy.

Yet it also set in motion a chain of events that eventually precipitated the end of confidence in the livre itself, as well as liquid assets denominated in livres. While Law clearly saw the untapped potential that could be unleashed if the French economy had a more efficient monetary system, and the immense profit that could be realized in the long run with the development of the Mississippi territory, he failed to see some of the other effects the end of monetary restraint would have. In other words, there were unintended consequences that Law didn’t foresee — and those consequences turned his entire endeavor into a Great Mistake.

Great Mistakes have plagued modern monetary policy as well. Among historians, there have been two Great Mistakes in Federal Reserve history, and the lessons from those periods continue to echo through the halls of the Eccles building in Washington, D.C. to this day. A full understanding of what is driving monetary policy decisions today is not possible without understanding the Fed’s earlier mistakes, and understanding those periods is essential to understanding the Fed’s current predicament.

The first Great Mistake in the history of the Federal Reserve occurred during the first two years of the Great Depression. In its failure to understand the catastrophic nature of the credit collapse in the early 1930s as it unfolded, and in its failure to appreciate the difference between nominal interest rates and real, inflation-(or deflation)-adjusted interest rates, the Federal Reserve unwittingly allowed monetary policy to dramatically tighten as the economic contraction deepened after 1930. Yet as that policy tightening took hold, nearly all Fed governors at the time assumed monetary policy was “loose.”

As prices throughout the economy began to fall, the Fed held its policy rate near the lowest level in its short history, leading most Fed governors to assume they had eased monetary policy enough. This sentiment was prevalent, in part, because the Fed had eased policy aggressively during the 1926–1927 recession, which turned out to be only a mild contraction. As a result, financial markets had boomed when the recession ended. In 1930, a number of Fed governors thought the markets and the economy needed to “correct” a good portion of the “excesses” seen in 1928 and 1929.

However, as the decline in prices eventually accelerated to a 10% annual rate in 1932, real interest rates rose as high as 12%. These high real, deflation-adjusted interest rates rapidly accelerated the contraction of credit, and helped turn the recession of 1930 into the Great Depression of the 1930s. The Federal Reserve has been haunted ever since by its inaction.

In a 2002 speech at a conference honoring the economist Milton Freedman, then-Fed Governor Ben Bernanke publicly apologized for this policy mistake on behalf of the Federal Reserve, telling his audience: “Regarding the Great Depression, … we did it. We’re very sorry. … We won’t do it again.” Little did Bernanke know as he spoke those words, he would personally be given the opportunity to put the main lessons learned from the Fed’s first Great Mistake into action just six years later, when the credit crisis hit in 2008.

The second Great Mistake in the history of the Federal Reserve was the set of events and policies that resulted in the Great Inflation of the 1970s. With the Great Depression still haunting the meetings of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), Fed governors were hypervigilant in monitoring for any signs of a contraction in credit and prices during the 1960s and early 1970s. Yet, in a mistake quite similar to their oversight during the first few years of the Great Depression, Fed officials continued to ignore real, inflation-adjusted interest rates. In addition, they also knowingly allowed political pressure pushing for easier monetary policy to impact their decision making.

As prices throughout the economy began to rise at faster rates beginning in the mid-1960s, the full weight of presidents Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon bore down on Fed chairmen McChesney Martin and Arthur Burns.

That Executive pressure poignantly began when President Johnson summoned Chairman Martin to Texas on December 6th, 1965. Johnson was incensed that the Fed had raised interest rates at its meeting on December 3rd, and he aggressively confronted Martin when he arrived as his ranch. In one of the most infamous encounters in Federal Reserve history, Johnson pressed Martin up against the wall in his living room and lambasted Martin for raising interest rates without his approval. He forcefully told Martin:

“You went ahead and did something that you knew I disapproved of, that can affect my entire term here. You took advantage of me and I’m not going to forget it.… You’ve got me into a position where you can run a rapier into me and you’ve run it. Martin, my boys are dying in Vietnam, and you won’t print the money I need.”

– President Lynden Johnson to Fed Chairman McChesney Martin, December 3, 1965

From that moment onward, real, inflation-adjusted interest rates pivoted to a downward trajectory, which continued through the Nixon presidency.

Nixon had lost the presidential election in 1960, he firmly believed, because unemployment had risen just prior to voting time. As a result, when he finally reached the presidency he relentlessly pushed policies that would counter any potential rise in unemployment. During this era in economic thinking, an unacceptable unemployment rate was considered anything above 4% — what the economic models of the time said was the full employment rate. In the relentless drive to keep the economy near full employment, the Federal Reserve, under pressure from the Executive Branch, ended monetary tightening campaigns early and reverted to expansionary policies whenever unemployment rose above 4%. This easy-policy approach played a large role in accelerating the inflation of prices through the 1970s.

Nixon also had a simpler and more pragmatic view of Federal Reserve independence than his predecessors did. When he installed Arthur Burns as chairman of the Fed in 1970, he succinctly summarized his opinion of his new Fed chairman:

“I respect his independence. However, I hope that independently he will conclude that my views are the ones he should follow.“

– President Richard Nixon on new Fed Chairman Arthur Burns, 1970

In wake of the 1970s Great Inflation, the Federal Reserve became hypervigilant in watching for both a contraction in credit and an unwanted acceleration in prices, all while maintaining a very public posture of independence from the rest of the federal government. These three priorities — avoiding a contraction in credit, avoiding an uncontrollable rise in prices, and maintaining independence from the rest of the federal government — reflect difficult lessons-learned from the first two Great Mistakes in Federal Reserve history.

Yet this hypervigilance for any sign of credit distress, or any incipient inflation, resulted in policy actions over the following decades that repeatedly sought to stabilize any disturbance, large or small. Whether it be a stock market crash, as in 1987, distress from an overleveraged hedge fund, as in the case of Long-Term Capital Management in 1998, or the fear of a potential rise in inflation above target, as was the case in 2016, the Fed remained vigilant in containing any potential credit or inflation risk. And by maintaining that hypervigilance, the Federal Reserve has unwittingly walked into a Third Great Mistake: the loss of control over monetary policy due to the buildup of debt.

As the economy, financial markets and government became increasingly accustomed to being bailed out in the event of any turbulence, leverage and debt soared to unprecedented post-war heights. The Greenspan Put became the Bernanke Put, and investors and borrowers came to understand all too well that the Federal Reserve would forcefully counter any downside deviation in the economy and financial markets.

Yet as debt and leverage increased, so did the fragility and sensitivity of the financial markets, resulting in a growing Catch 22 for monetary policy: increasing debt demanded increasingly aggressive monetary responses to downturns, which encouraged even higher indebtedness. And since the financial crisis in 2008, monetary policy has carefully operated at the mercy of this elevated leverage and debt, which has remained above 300% of U.S. GDP since 2005.

The latest full figures show total U.S. debt at $74.177 trillion as of the second quarter of 2021, which represented 320% of GDP. More than a third of that is represented by the federal government’s debt, which rose above $30 trillion just a few weeks ago, on January 31st. The federal debt has climbed more than $7 trillion just over the past two years, and this enormous obligation places an equally enormous political burden on monetary policy, the likes of which has not been seen since the days of Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon.

* * *

In his most recent press conference on January 26th, current Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell sought to prepare the markets for the end of zero-percent short-term interest rates, as well as the end of the pandemic-induced purchasing of Treasury and mortgage-backed securities. With inflation proving far more durable and widespread than the Fed thought remotely possible just a year ago, Powell made it clear it was time for the highly accommodative stance of U.S. monetary policy over the past two years to end.

To a question at his press conference about how fast interest rates may begin to rise, Powell offered this response:

We know that the economy is in a very different place than it was when we began raising rates in 2015. Specifically, the economy is now much stronger. The labor market is far stronger. Inflation is running well above our 2 percent target, much higher than it was at that time. And these differences are likely to have important implications for the appropriate pace of policy adjustments…

I think there’s quite a bit of room to raise interest rates without threatening the labor market. This is, by so many measures, a historically tight labor market, record levels of job openings, of quits. Wages are moving up at the highest pace they have in decades. If you look at surveys of workers, they find jobs plentiful. Look at surveys of companies, they find workers scarce. And all of those readings are at levels really that we haven’t seen in a long time and, in some cases, ever. So, this is a very, very strong labor market. And my strong sense is that we can move rates up without having to, you know, severely undermine it.

It is important to remember that the Federal Reserve views its public comments, such as those above, as one of the most important tools it has available to achieve the goals of its dual mandate. So, when the chair of the Federal Reserve makes it clear he views the labor market as historically tight, that is an unambiguous message to the markets that monetary policy is about to pivot away from supporting the employment recovery to focusing on inflation. Even though total employment in the U.S. remains 2.875 million jobs below where it was two years ago in February 2020, just before the pandemic lockdowns began, from a monetary policy perspective, the Fed now views the employment side of its dual mandate as having been achieved.

It is also important to remember that the policies of the Federal Reserve almost always follow the financial markets, and it is clear the markets have been slowly pricing in the end of the most aggressive monetary response in Federal Reserve history over the past year.

While the Federal Funds rate appears poised to “lift off” from zero in March, yields throughout the yield curve have been lifting off since late 2020. Longer-term Treasury yields began rising from their ultra-low levels in October 2020, and since then the lift-off in yields has moved progressively down the yield curve toward shorter maturities: the 5-Year Treasury yield began rising in February 2021; the 2-Year Treasury yield began rising in October 2021; and the 3-Month (13-Week) Treasury yield began rising in January of this year. And each successive pivot higher along the yield curve corresponded with an equally significant technical pivot in the equity market.

When the 5-Year Treasury yield pivoted higher in February 2021, as noted by the #1 on the chart above, it marked the climax of the meme-stock frenzy, and the massive short-squeezes it fomented in stocks like GameStop. It also marked the peak of the most speculative tech names, such as those which have been the focus of Cathy Woods’ ARKK fund, which has fallen 64% from its peak a year ago. When the 2-Year Treasury began rising last October, as noted by the #2 in the chart, it marked the peak of the broader Nasdaq indexes, which have since fallen more than 15%. The small-cap Russell 2000 reached its highest point the following month. And when the 13-Week Treasury yield began rising at the beginning of January, as noted by #3, the broader equity market began to decline.

These significant interest rate pivots, coincident with the progressive erosion of breadth in the equity market, unfolded in plain sight. It is a textbook example of what the peak of a major market bubble looks like, as the peaks in 1929 and 2000 unfolded in an almost identical progression.

However, the erosion over the past year was all the more remarkable since quantitative easing continued throughout the entire progression: everything that has been seen up to this point in the markets has been with the Federal Reserve still buying tens of billions of Treasury and mortgage-backed bonds every month. We have yet to see how the markets will function without that monetary support, let alone with an increasing Federal Funds rate, or a shrinking Fed balance sheet. That market environment lies ahead.

In his press conference, Powell also made it clear that the Fed, in addition to raising interest rates, intends to eventually begin shrinking its balance sheet after the end of its current quantitative easing programs:

Asset purchases were enormously important at the beginning of the recovery in terms of restoring market function as they were at — right after the — in the critical phase of the global financial crisis. And then, after, they were a macroeconomic tool to support demand. And now the economy no longer needs this highly accommodative policy that we put in place. So it’s time to stop asset purchases first and then, at the appropriate time, start to shrink the balance sheet.

Now, the balance sheet is substantially larger than it needs to be. We’ve identified the end state as — in amounts needed to implement monetary policy efficiently, effectively in the ample reserve regime. So there’s a substantial amount of shrinkage in the balance sheet to be done. That’s going to take some time.

We want that process to be orderly and predictable … [but] I don’t think it’s possible to say exactly how this is going to go. And we’re going to need to be, as I’ve mentioned, nimble about this…

* * *

In the spring of 1720, John Law began to understand the perilous monetary situation France was in, as the Banque Royale continued to rapidly expand the money supply. Although Company of the West shares remained aloft, which encouraged citizens to exchange their debt holdings for shares, there were clear signs that confidence in banknotes was beginning to falter: prices throughout France had begun to rise, including the price of gold and silver, despite all the legal prohibitions.

Although Law desperately needed Company of the West shares to remain high until he could complete the exchange of shares for the king’s debt, it dawned on him that if confidence in banknotes cracked, his entire endeavor to remake France’s monetary system and spur the development of the Mississippi territory would quickly unravel. In a desperate attempt to maintain confidence, Law decided in May 1720 to shrink the supply of banknotes back down to his estimate of the total value of real assets in France. In the end, however, the attempt to restore monetary balance only accelerated the collapse, as the general public, unaware until then how little backed their banknotes, suddenly panicked and rushed for the exit.

In the aftermath of the Mississippi Bubble, the statutory value of the livre was returned to a specific amount of gold and silver, and over the following decade, many of the debts which had been exchanged for then-worthless Company of the West shares were restored to their former value. The gold and silver contract clauses that had been voided were reinstated, and the courts spent years working through the remittances on a case-by-case basis. These actions reestablished a stable monetary order, which remained in place until the French Revolution seventy years later. The Great Mistake of Law’s Banque Royale was over.

In the months and years ahead, we are going to see if Chair Powell and the Federal Reserve will be able to do what John Law failed to accomplish: restore monetary balance before confidence in the dollar erodes and inflation takes root. The Fed now appears to be aware that a base money supply of $9 trillion is not without risks, either in the form of generating significant inflation, or in terms of encouraging a new inflationary psychology — i.e. an erosion of confidence in the dollar — taking root in the broader public. The Fed has now sent clear signals that interest rates are about to rise, and the base money supply is about to shrink.

The big question is how much headway the Fed will ultimately make toward achieving these goals before its effort to confront rising prices runs aground on the $74 trillion in debt in the U.S. economy, over $30 trillion of which is the obligation of the federal government. As John Law discovered, despite the logic of his plan to restore monetary balance, events ultimately spiraled out of his control. The Federal Reserve similarly lost control during its first two Great Mistakes. While it is clear Chair Powell and other Fed officials see what must be done in order to avoid a long-term erosion of confidence in the dollar, it is not so clear they see the pressures that will come to bear in doing so.

* * *

The above is part 1 of Volume I Issue II of The Macro Value Monitor, a publication that focuses on Monetary History, Market Myths, Investing Legends, and Real Global Value. Part 2 of February’s issue, The End of Ultra-Low Yields and the Standard 60/40 Portfolio, is available here.

Return to Recent Memos, Articles and Letters

The content of this document is provided as general information and is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment or other advice. This material is not to be construed as a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any security, financial product, instrument or to participate in any particular trading strategy. Not all securities, products or services described are available in all countries, and nothing herein constitutes an offer or solicitation of any securities, products or services in any jurisdiction where their offer or sale is not qualified or exempt from registration or otherwise legally permissible.

Although the material herein is based upon information considered reliable and up-to-date, Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC does not assure that this material is accurate, current, or complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. Content in this document may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted, in whole or in part, without prior written consent from Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC — which is usually gladly given, as long as its use includes clear and proper attribution. Contact us for more information.

© Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC

Investment Management

Before investing, we will discuss your goals and risk tolerances with you to see if a separately managed account at Sitka Pacific would be a good fit. To contact us for a free consultation, visit Getting Started.

Macro Value Monitor

To read a selection of recent client letters and be alerted when new letters are posted to our public site, visit Recent Client Letters.