This Era May Come to Be Remembered as the Federal Reserve’s Third Great Mistake

February 25, 2021

The success of the Federal Reserve System is apparent today…These [recent] events are deplorable, but they were of course inevitable and could not have been avoided.

– Charles Hamlin, Federal Reserve Board Governor, November 8, 1929

While the Federal Reserve would always accommodate the Treasury up to a point, the charge could be made – and was being made – that the System had accommodated the Treasury to an excessive degree. Although [Chairman Burns] was not a monetarist, he found a basic and inescapable truth in the monetarist position that inflation could not have persisted over a long period of time without a highly accommodative monetary policy.

– FOMC Meeting Minutes, March 9, 1974

The inflation rate over the longer run is primarily determined by monetary policy, and hence the Committee has the ability to specify a longer-run goal for inflation… In order to anchor longer-term inflation expectations at this [2%] level, the Committee seeks to achieve inflation that averages 2 percent over time, and therefore judges that, following periods when inflation has been running persistently below 2 percent, appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time.

– Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy, FOMC, August 27, 2020

The Great Inflation of the 1960s and 70s, the earliest stages of which were already underway when Graham spoke at the St. Francis Hotel, eventually produced some of the most astonishing economic dislocations in U.S. history. After 1963, there would be a parabolic increase in consumer prices, leaving the Consumer Price Index at three times its former level. Commodity prices would also triple. Near the end of the most rapid phase of that increase in prices, interest rates would reach the highest levels in U.S. history, and risk assets would sink to the lowest valuations in fifty years.

Yet as the earliest stages of the monetary expansion were underway in late 1963, none of the oncoming inflation of prices was reflected in the markets. Interest rates were low and stable, and valuations of risk assets were high and still rising. Though the impacts of rising inflation represented risks which were embedded in the prices and valuations at the time, the long process of pricing in those risks lay ahead.

Within the Federal Reserve System, the inflation which plagued the U.S. in the 1970s is known as the Second Great Mistake. The primary reason it is known as a mistake is because many of those within the Fed at the time understood the inflationary implications of the policies which were being enacted, but monetary policy traveled down that road anyway. It remains a case study of an institution that lost sight of its long-term goals while reacting to short-term problems. At every step along the road to higher inflation, the costs of prioritizing long-term price stability over the economic and market conditions at the time were, again and again, deemed too high.

It also represents another example, in a long history of examples, of what happens when political pressures are allowed to railroad monetary policy decisions. That many at the Fed were aware of how heavily monetary policy was being influenced by political considerations, while at the same time allowing that influence to continue, is another reason the inflation of that era is known as a mistake. As the quote above from the Federal Open Market Committee meeting minutes in March 1974 attests, the Fed was well aware that it was the main source of the inflation problem, and that its delayed interest rate hikes and accommodation of ever-expanding debt sales by the Treasury had resulted in higher money supply growth rates and rising inflation (known as the “even keel” policy, the Fed would steady the markets by flooding the banking system with reserves during large Treasury debt sales, but would repeatedly fail to recall all of the additional reserves when the debt sales were complete). Yet it would be another six long, inflationary years after 1974 before decisive action would be taken to reassert the Fed’s focus on long-term goals.

Underlying the many decisions that led to the inflation of the 1970s, however, were the haunting institutional memories of the Fed’s First Great Mistake — the Great Depression. The deflationary spiral which took root after 1929 was not the first depression the U.S. had endured, as there had been downturns severe enough to be labeled depressions in the 1800s. However, it was the first depression after the Federal Reserve had been created, and the economic cataclysm that followed was seen as a failure of the System which had been established, in part, to ensure that panics and depressions were relics of the past.

At the heart of the First Great Mistake was monetary policy’s role in fomenting the speculative boom in the late 1920s, followed by the failure of the Fed to understand how restrictive monetary policy had become during the early 1930s. As was mentioned earlier, between 1929 and 1933 real interest rates soared above 10%, and consumer prices in the U.S. fell 27% as banks failed and credit contracted. The primary driver of the bank failures was a real estate bust — in this case, a farmland bust. As prices for wheat and other cash crops plummeted, farmers across the Midwest found themselves unable to meet their obligations to their local banks. And as local and regional banks found themselves with a soaring inventory of seized property that was no longer generating income, they began folding in increasing numbers. Credit contracted as more banks failed, and the deflationary spiral worsened.

Yet during those early years of the Great Depression, many within the Fed considered the downturn to be a healthy, restorative correction of the excesses of the preceding boom. The quote above of Charles Hamlin, who had been a member of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors since the Fed’s founding in 1914, and was its first chairman, exemplified this sentiment. For many at the Fed, the speculative excesses in the stock market in 1928 and 1929 had been partly the result of monetary policy’s overreaction to the mild recession in 1926–1927. As a result of that experience of overreacting to a mild recession and triggering a speculative bubble, the economy seemed long overdue for a more substantial recession, and many at the Fed felt the economy would be best served if they did not overreact again by easing monetary policy too much in 1930.

The actions of the Federal Reserve in the nine decades since that moment have been haunted by the misjudgment of the severity of the downturn after 1929, and the long road to recovery that followed. In addition, the Fed learned during those years that not only is the economy at stake when it fails to respond aggressively enough, but its independence is at stake as well. As Roosevelt took the initiative and devalued gold in 1933, in a desperate effort to expand the money supply, it marked the beginning of the Treasury’s takeover of monetary policy. The Fed would not regain its independent footing until after the Treasury-Fed Accord of 1951.

The year 2020 marked an almost cosmic confluence of the lessons which have been seared into the institutional memory of the Federal Reserve since its founding, and it is difficult to understate the impact these lessons had on the policy actions over the past year. An important lesson the Fed learned during the First Great Mistake was fairly straightforward: a failure to ease monetary policy enough during a severe downturn risks a complete loss of institutional independence. And a key lesson learned during both the First Great Mistake and the Second Great Mistake was that losing control of long-term price stability, in either direction, risks complete loss of control over interest rates in the short term. Over the last forty years, the Fed has done everything it could to avoid making these same mistakes, and risk losing independence or control, and in doing so, it has perhaps unwittingly stumbled into its Third Great Mistake.

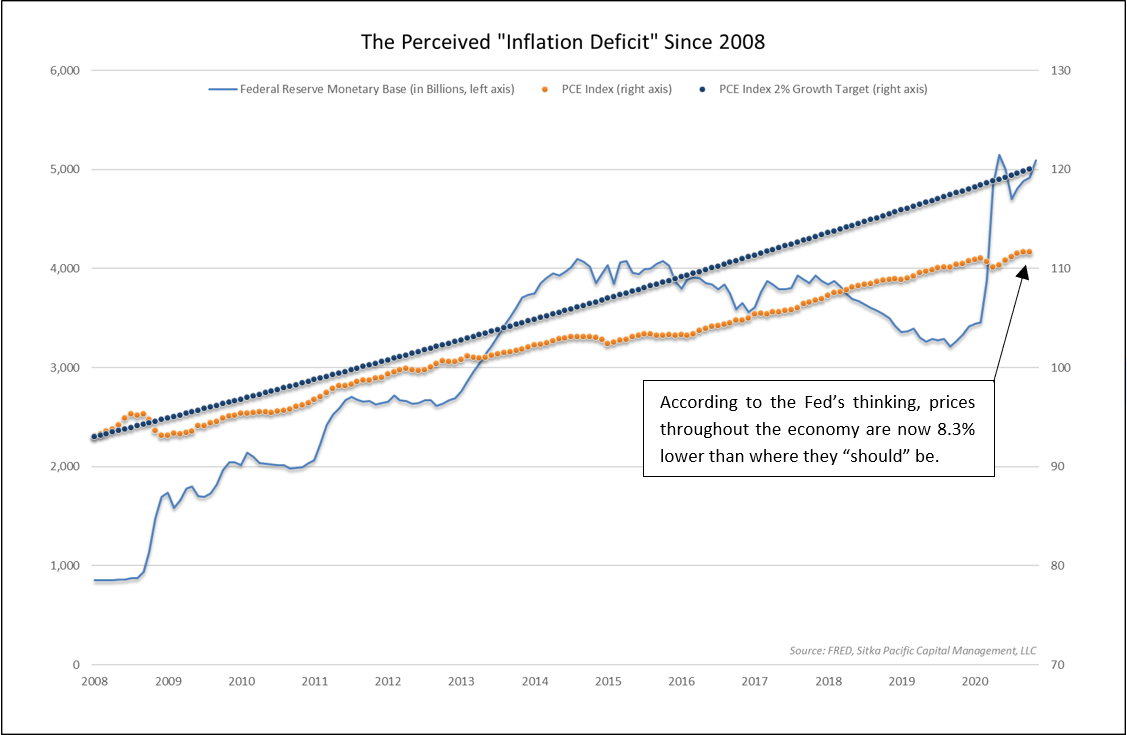

Before the pandemic arrived, the Federal Reserve had long sought to understand why inflation had consistently trended below its target since the financial crisis in 2008. Despite holding short-term interest rates near zero, and despite expanding its balance sheet by more than it had during the 1930s, the Fed’s preferred method of measuring inflation — the PCE Price Index — had never really picked up as the economy continued to recover. Contrary to the typical postwar experience, the economic recovery progressed with little inflation. As the decade wore on and the Fed felt compelled to begin normalizing monetary policy, PCE-measured inflation slowed further. By 2020, prices throughout the economy were well below where they would be had the Fed’s inflation target been achieved.

As recently as 2019, the Fed sounded an optimistic note about inflation to eventually returning to its 2% target as the economy continued to recover from the financial crisis. In its 2019 Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy, there was no hint in the statement that indicated otherwise. But as with so many other aspects of life over the past year, the pandemic prompted a strategic reassessment, and the 2020 Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy outlined a major shift in the Fed’s approach going forward: no longer content with the inflation rate merely reaching its 2% goal in any given year, monetary policy would now aim for inflation averaging 2% over time, so prices would more closely follow the Fed’s intended long-term path.

Aside from the policy reactions to blunt the economic impact of the pandemic, this revision of the Fed’s approach to achieving its long-term goal for inflation is the most significant policy event of the past year. It effectively means the Fed now intends to “make up for lost inflation” by keeping monetary policy looser for longer than it would have in prior cycles. Going forward, the Fed does not intend to repeat the post-financial-crisis experience of inflation stubbornly remaining below its 2% target — it wants inflation to have recovered its recessionary trend deficit before monetary stimulus recedes. This shift in the Fed’s approach also means that the past year effectively marked the beginning of a new era of negative real interest rates.

What seems to have been lost amid the fiscal and monetary policy reactions to the pandemic is that the Fed may have already lost control over short-term monetary policy, due to the imbalances built up over the past several decades. The past year also showed that monetary policy in the U.S. has already suffered a significant loss of independence to the Treasury. The early stages of the first two Great Mistakes in Fed history were defined by a similar loss of control and independence, and both were followed by inflationary episodes that defied the Fed’s goal of long-term price stability. In a twist of irony, however, this time a more inflationary outcome appears to be just what official Fed policy is now seeking.

With short-term interest rates having been pinned back down to the zero-bound by the recession, which so quickly unwound a years-long campaign to increase its room to maneuver leading up to 2019, the Federal Reserve now recognizes that its policy response to the credit crisis was inadequate. Instead of fearing a return of inflation, the Fed made it clear this past year that its primary goal going forward is to avoid a return to the low-inflation environment of the past decade. In the Fed’s reassessment, the fear of inflation in the years following the financial crisis resulted in an approach that was too tentative, and Fed officials have made it clear that monetary policy will not be so tentative in the years following this recession.

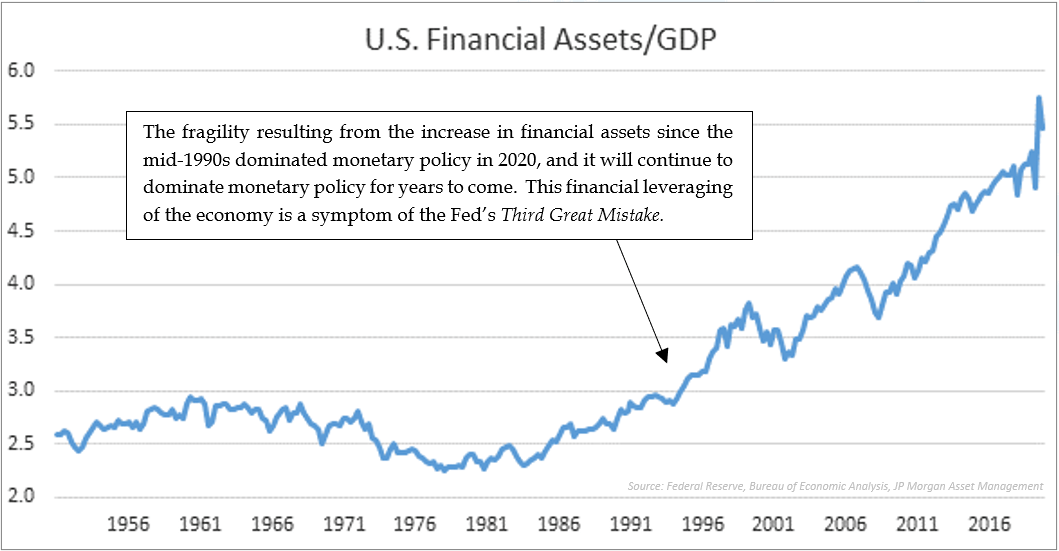

It appears, however, that the Fed has already lost the ability to raise interest rates, even if it wanted to. As a result of its efforts over the past four decades to avoid a return of 1970s-like inflation, and its efforts over the past two decades to avoid a return of 1930s-like deflation, the economy, the financial markets and the government are now so leveraged that higher interest rates are untenable. The chart above highlights the value of all financial assets relative to the size of the economy, and all of those assets are interest-rate sensitive. With so much asset value now at stake relative to the economy, raising interest rates is most likely no longer a realistic option.

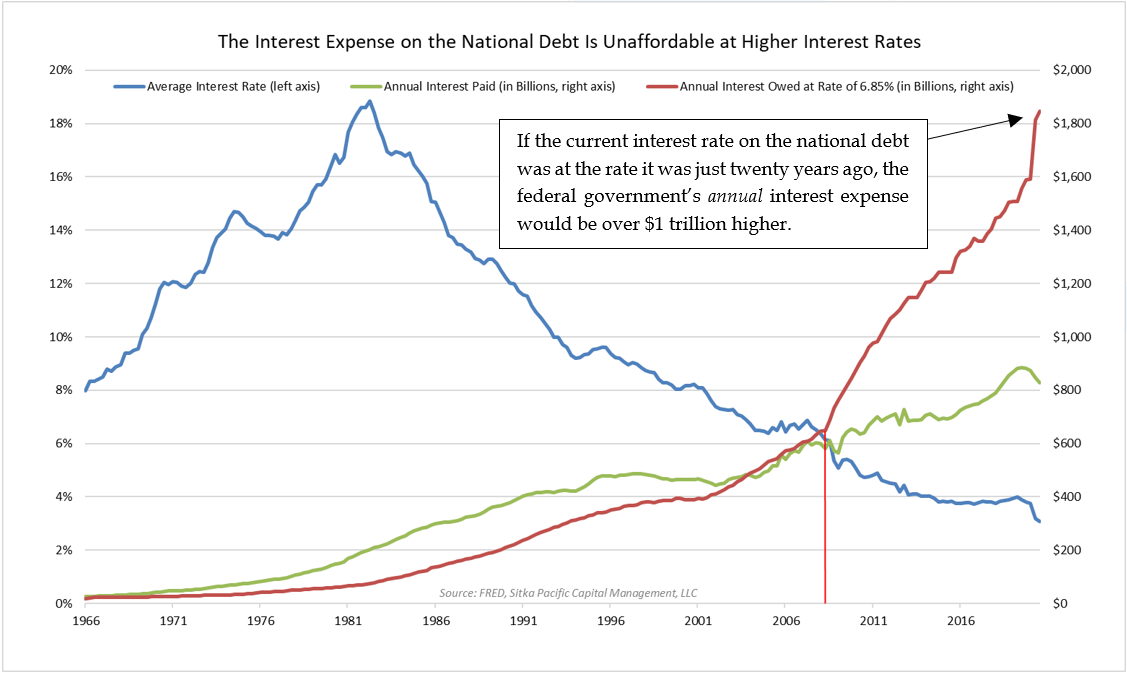

At the same time, the federal government is no longer in a position to afford higher interest rates. With the increase in the federal government’s debt over the past twenty years, there is now more political incentive for continued low interest rates than at any other time since the Treasury took over monetary policy during World War II. Since the interest payments the Federal Reserve receives on its Treasury holdings are returned to the Treasury, the actual net interest expense is lower than is shown by the green line below. However, the red line shows what the annual interest expense would be if the interest rate on the national debt returned to the level it was just twenty years ago.

In what may serve as a poignant symbol of this era, Janet Yellen was recently confirmed as the 78th Secretary of the Treasury. This appointment effectively places both fiscal and monetary policy in the hands of those who deeply understand the need for inflation, and are committed to enacting policies which will avoid a repeat of the low-inflation environment of the post-credit-crisis period.

At her confirmation hearing, Yellen addressed the growing national debt in her opening statement: Neither the president-elect, nor I, propose this [latest] relief package without an appreciation for the country’s debt burden. But right now, with interest rates at historic lows, the smartest thing we can do is act big. Later, she referred to the lack of increase in debt service in recent years: In a very low interest-rate environment like we’re in, what we’re seeing is that even though the amount of debt relative to the economy has gone up, the interest burden hasn’t. While it is certainly true the interest burden has not risen in recent years, that will only remain the case if interest rates remain low until the debt burden relative to the economy is far lower than it is today. So it appears the major stakeholders are now all aligned on the desirability for higher inflation, and the need for interest rates to remain low.

The Third Great Mistake means there is no longer an alternative to higher inflation, and there is also no pain-free way for monetary policy prevent inflation from spiraling higher than intended. It is reminiscent of the circumstances in the late 1960s, and it is fitting that financial markets appear to be in a similar position as well: interest rates are low, risk asset valuations are high, and there is a speculative fervor which has apparently concluded that the entire equity market is now a one decision investment. Meanwhile, though we do not know how successful the efforts to induce higher inflation will ultimately be in the years ahead, real assets are quietly trading as if inflation is nowhere in sight.

* * *

This is an excerpt from our 2021 Annual Client Letter. This and other letters are available in their entirety at Recent Articles and Client Letters.

Follow Sitka Pacific at LinkedIn

Sitka Pacific Capital Management, LLC is an absolute return asset manager helping investors and advisors gain stability and independence from the markets. The content of this article is provided as general information only and is not intended to provide investment or other advice. This material is not to be construed as a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any security, financial product, instrument or to participate in any particular trading strategy. Sitka Pacific Capital Management, LLC provides investment advice solely through the management of its client accounts. This article may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted, in whole or in part, without prior written consent from Sitka Pacific Capital Management, LLC.

© Sitka Pacific Capital Management, LLC

This Era May Come to Be Remembered as the Federal Reserve’s Third Great Mistake

February 25, 2021

The success of the Federal Reserve System is apparent today…These [recent] events are deplorable, but they were of course inevitable and could not have been avoided.

– Charles Hamlin, Federal Reserve Board Governor, November 8, 1929

While the Federal Reserve would always accommodate the Treasury up to a point, the charge could be made – and was being made – that the System had accommodated the Treasury to an excessive degree. Although [Chairman Burns] was not a monetarist, he found a basic and inescapable truth in the monetarist position that inflation could not have persisted over a long period of time without a highly accommodative monetary policy.

– FOMC Meeting Minutes, March 9, 1974

The inflation rate over the longer run is primarily determined by monetary policy, and hence the Committee has the ability to specify a longer-run goal for inflation… In order to anchor longer-term inflation expectations at this [2%] level, the Committee seeks to achieve inflation that averages 2 percent over time, and therefore judges that, following periods when inflation has been running persistently below 2 percent, appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time.

– Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy, FOMC, August 27, 2020

The Great Inflation of the 1960s and 70s, the earliest stages of which were already underway when Graham spoke at the St. Francis Hotel, eventually produced some of the most astonishing economic dislocations in U.S. history. After 1963, there would be a parabolic increase in consumer prices, leaving the Consumer Price Index at three times its former level. Commodity prices would also triple. Near the end of the most rapid phase of that increase in prices, interest rates would reach the highest levels in U.S. history, and risk assets would sink to the lowest valuations in fifty years.

Yet as the earliest stages of the monetary expansion were underway in late 1963, none of the oncoming inflation of prices was reflected in the markets. Interest rates were low and stable, and valuations of risk assets were high and still rising. Though the impacts of rising inflation represented risks which were embedded in the prices and valuations at the time, the long process of pricing in those risks lay ahead.

Within the Federal Reserve System, the inflation which plagued the U.S. in the 1970s is known as the Second Great Mistake. The primary reason it is known as a mistake is because many of those within the Fed at the time understood the inflationary implications of the policies which were being enacted, but monetary policy traveled down that road anyway. It remains a case study of an institution that lost sight of its long-term goals while reacting to short-term problems. At every step along the road to higher inflation, the costs of prioritizing long-term price stability over the economic and market conditions at the time were, again and again, deemed too high.

It also represents another example, in a long history of examples, of what happens when political pressures are allowed to railroad monetary policy decisions. That many at the Fed were aware of how heavily monetary policy was being influenced by political considerations, while at the same time allowing that influence to continue, is another reason the inflation of that era is known as a mistake. As the quote above from the Federal Open Market Committee meeting minutes in March 1974 attests, the Fed was well aware that it was the main source of the inflation problem, and that its delayed interest rate hikes and accommodation of ever-expanding debt sales by the Treasury had resulted in higher money supply growth rates and rising inflation (known as the “even keel” policy, the Fed would steady the markets by flooding the banking system with reserves during large Treasury debt sales, but would repeatedly fail to recall all of the additional reserves when the debt sales were complete). Yet it would be another six long, inflationary years after 1974 before decisive action would be taken to reassert the Fed’s focus on long-term goals.

Underlying the many decisions that led to the inflation of the 1970s, however, were the haunting institutional memories of the Fed’s First Great Mistake — the Great Depression. The deflationary spiral which took root after 1929 was not the first depression the U.S. had endured, as there had been downturns severe enough to be labeled depressions in the 1800s. However, it was the first depression after the Federal Reserve had been created, and the economic cataclysm that followed was seen as a failure of the System which had been established, in part, to ensure that panics and depressions were relics of the past.

At the heart of the First Great Mistake was monetary policy’s role in fomenting the speculative boom in the late 1920s, followed by the failure of the Fed to understand how restrictive monetary policy had become during the early 1930s. As was mentioned earlier, between 1929 and 1933 real interest rates soared above 10%, and consumer prices in the U.S. fell 27% as banks failed and credit contracted. The primary driver of the bank failures was a real estate bust — in this case, a farmland bust. As prices for wheat and other cash crops plummeted, farmers across the Midwest found themselves unable to meet their obligations to their local banks. And as local and regional banks found themselves with a soaring inventory of seized property that was no longer generating income, they began folding in increasing numbers. Credit contracted as more banks failed, and the deflationary spiral worsened.

Yet during those early years of the Great Depression, many within the Fed considered the downturn to be a healthy, restorative correction of the excesses of the preceding boom. The quote above of Charles Hamlin, who had been a member of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors since the Fed’s founding in 1914, and was its first chairman, exemplified this sentiment. For many at the Fed, the speculative excesses in the stock market in 1928 and 1929 had been partly the result of monetary policy’s overreaction to the mild recession in 1926–1927. As a result of that experience of overreacting to a mild recession and triggering a speculative bubble, the economy seemed long overdue for a more substantial recession, and many at the Fed felt the economy would be best served if they did not overreact again by easing monetary policy too much in 1930.

The actions of the Federal Reserve in the nine decades since that moment have been haunted by the misjudgment of the severity of the downturn after 1929, and the long road to recovery that followed. In addition, the Fed learned during those years that not only is the economy at stake when it fails to respond aggressively enough, but its independence is at stake as well. As Roosevelt took the initiative and devalued gold in 1933, in a desperate effort to expand the money supply, it marked the beginning of the Treasury’s takeover of monetary policy. The Fed would not regain its independent footing until after the Treasury-Fed Accord of 1951.

The year 2020 marked an almost cosmic confluence of the lessons which have been seared into the institutional memory of the Federal Reserve since its founding, and it is difficult to understate the impact these lessons had on the policy actions over the past year. An important lesson the Fed learned during the First Great Mistake was fairly straightforward: a failure to ease monetary policy enough during a severe downturn risks a complete loss of institutional independence. And a key lesson learned during both the First Great Mistake and the Second Great Mistake was that losing control of long-term price stability, in either direction, risks complete loss of control over interest rates in the short term. Over the last forty years, the Fed has done everything it could to avoid making these same mistakes, and risk losing independence or control, and in doing so, it has perhaps unwittingly stumbled into its Third Great Mistake.

Before the pandemic arrived, the Federal Reserve had long sought to understand why inflation had consistently trended below its target since the financial crisis in 2008. Despite holding short-term interest rates near zero, and despite expanding its balance sheet by more than it had during the 1930s, the Fed’s preferred method of measuring inflation — the PCE Price Index — had never really picked up as the economy continued to recover. Contrary to the typical postwar experience, the economic recovery progressed with little inflation. As the decade wore on and the Fed felt compelled to begin normalizing monetary policy, PCE-measured inflation slowed further. By 2020, prices throughout the economy were well below where they would be had the Fed’s inflation target been achieved.

As recently as 2019, the Fed sounded an optimistic note about inflation to eventually returning to its 2% target as the economy continued to recover from the financial crisis. In its 2019 Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy, there was no hint in the statement that indicated otherwise. But as with so many other aspects of life over the past year, the pandemic prompted a strategic reassessment, and the 2020 Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy outlined a major shift in the Fed’s approach going forward: no longer content with the inflation rate merely reaching its 2% goal in any given year, monetary policy would now aim for inflation averaging 2% over time, so prices would more closely follow the Fed’s intended long-term path.

Aside from the policy reactions to blunt the economic impact of the pandemic, this revision of the Fed’s approach to achieving its long-term goal for inflation is the most significant policy event of the past year. It effectively means the Fed now intends to “make up for lost inflation” by keeping monetary policy looser for longer than it would have in prior cycles. Going forward, the Fed does not intend to repeat the post-financial-crisis experience of inflation stubbornly remaining below its 2% target — it wants inflation to have recovered its recessionary trend deficit before monetary stimulus recedes. This shift in the Fed’s approach also means that the past year effectively marked the beginning of a new era of negative real interest rates.

What seems to have been lost amid the fiscal and monetary policy reactions to the pandemic is that the Fed may have already lost control over short-term monetary policy, due to the imbalances built up over the past several decades. The past year also showed that monetary policy in the U.S. has already suffered a significant loss of independence to the Treasury. The early stages of the first two Great Mistakes in Fed history were defined by a similar loss of control and independence, and both were followed by inflationary episodes that defied the Fed’s goal of long-term price stability. In a twist of irony, however, this time a more inflationary outcome appears to be just what official Fed policy is now seeking.

With short-term interest rates having been pinned back down to the zero-bound by the recession, which so quickly unwound a years-long campaign to increase its room to maneuver leading up to 2019, the Federal Reserve now recognizes that its policy response to the credit crisis was inadequate. Instead of fearing a return of inflation, the Fed made it clear this past year that its primary goal going forward is to avoid a return to the low-inflation environment of the past decade. In the Fed’s reassessment, the fear of inflation in the years following the financial crisis resulted in an approach that was too tentative, and Fed officials have made it clear that monetary policy will not be so tentative in the years following this recession.

It appears, however, that the Fed has already lost the ability to raise interest rates, even if it wanted to. As a result of its efforts over the past four decades to avoid a return of 1970s-like inflation, and its efforts over the past two decades to avoid a return of 1930s-like deflation, the economy, the financial markets and the government are now so leveraged that higher interest rates are untenable. The chart above highlights the value of all financial assets relative to the size of the economy, and all of those assets are interest-rate sensitive. With so much asset value now at stake relative to the economy, raising interest rates is most likely no longer a realistic option.

At the same time, the federal government is no longer in a position to afford higher interest rates. With the increase in the federal government’s debt over the past twenty years, there is now more political incentive for continued low interest rates than at any other time since the Treasury took over monetary policy during World War II. Since the interest payments the Federal Reserve receives on its Treasury holdings are returned to the Treasury, the actual net interest expense is lower than is shown by the green line below. However, the red line shows what the annual interest expense would be if the interest rate on the national debt returned to the level it was just twenty years ago.

In what may serve as a poignant symbol of this era, Janet Yellen was recently confirmed as the 78th Secretary of the Treasury. This appointment effectively places both fiscal and monetary policy in the hands of those who deeply understand the need for inflation, and are committed to enacting policies which will avoid a repeat of the low-inflation environment of the post-credit-crisis period.

At her confirmation hearing, Yellen addressed the growing national debt in her opening statement: Neither the president-elect, nor I, propose this [latest] relief package without an appreciation for the country’s debt burden. But right now, with interest rates at historic lows, the smartest thing we can do is act big. Later, she referred to the lack of increase in debt service in recent years: In a very low interest-rate environment like we’re in, what we’re seeing is that even though the amount of debt relative to the economy has gone up, the interest burden hasn’t. While it is certainly true the interest burden has not risen in recent years, that will only remain the case if interest rates remain low until the debt burden relative to the economy is far lower than it is today. So it appears the major stakeholders are now all aligned on the desirability for higher inflation, and the need for interest rates to remain low.

The Third Great Mistake means there is no longer an alternative to higher inflation, and there is also no pain-free way for monetary policy prevent inflation from spiraling higher than intended. It is reminiscent of the circumstances in the late 1960s, and it is fitting that financial markets appear to be in a similar position as well: interest rates are low, risk asset valuations are high, and there is a speculative fervor which has apparently concluded that the entire equity market is now a one decision investment. Meanwhile, though we do not know how successful the efforts to induce higher inflation will ultimately be in the years ahead, real assets are quietly trading as if inflation is nowhere in sight.

* * *

This is an excerpt from our 2021 Annual Client Letter. This and other letters are available in their entirety at Recent Articles and Client Letters.

Follow Sitka Pacific at LinkedIn

Sitka Pacific Capital Management, LLC is an absolute return asset manager helping investors and advisors gain stability and independence from the markets. The content of this article is provided as general information only and is not intended to provide investment or other advice. This material is not to be construed as a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any security, financial product, instrument or to participate in any particular trading strategy. Sitka Pacific Capital Management, LLC provides investment advice solely through the management of its client accounts. This article may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted, in whole or in part, without prior written consent from Sitka Pacific Capital Management, LLC.

© Sitka Pacific Capital Management, LLC

Investment Management

Before investing, we will discuss your goals and risk tolerances with you to see if a separately managed account at Sitka Pacific would be a good fit. To contact us for a free consultation, visit Getting Started.

Macro Value Monitor

To read a selection of recent client letters and be alerted when new letters are posted to our public site, visit Recent Client Letters.