The Policy Repercussions of the Third Great Mistake Are Slowly Becoming More Apparent

By Brian McAuley

November 15, 2021

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said on Friday the U.S. central bank should begin reducing its asset purchases soon, but should not yet raise interest rates because employment is still too low and high inflation will likely abate next year as pressures from the COVID-19 pandemic fade.

“I do think it’s time to taper; I don’t think it’s time to raise rates,” Powell said in a virtual appearance before a conference. “We think we can be patient and allow the labor market to heal.” That outlook, Powell emphasized, is only the most likely case, adding that if inflation – already higher and lasting longer than earlier expected – moves persistently upward, the Fed would act.

The central bank, however, is facing a delicate balancing act in its dual mandate to seek full employment and stable prices. Consumer prices have been rising at more than twice the Fed’s 2% target, but employment is still well below the pre-pandemic level.

– Reuters, October 22, 2021

As much as last year centered around the Covid-19 pandemic and its impact on the economy, the major topic of discussion in the financial markets this year has been centered around inflation, and its prospective impact on monetary policy. During the first half of this year, Chair Jerome Powell and other Federal Reserve officials were consistently adamant that the increase in prices rippling through the economy was the result of transitory factors stemming from the pandemic itself and its direct impact on the economy’s ability to deliver goods and services efficiently. Since the rise in prices was attributed to causes which would dissipate over time as the economic impact of the pandemic waned, the Fed felt justified in more or less ignoring prices while focusing exclusively on the employment half of its dual mandate. And since there remained millions fewer people working than before the pandemic, the exclusive focus on employment seemed justified.

This approach was also in line with the Federal Reserve’s new policy framework, which was announced in August of last year. This new framework was the result of a critical assessment of the decade following the financial crisis, and the persistence of below-target inflation despite low interest rates and the first use of quantitative easing in seventy years. The assessment concluded that monetary policy had begun tightening prematurely under the assumption that inflation would revert to 2% over time as the effects of the financial crisis faded, when in fact inflation subsequently remained below 2%. This not only resulted in low inflation rates and low long-term Treasury yields later in the decade, it also severely limited the Federal Reserve’s room to maneuver in the event of another downturn in the economy, since short-term interest rates remained low. The new policy framework aimed to alleviate these circumstances by reframing the inflation half of the Fed’s dual mandate to aim for an average 2% inflation rate over time, instead of maintaining a 2% ceiling. This new framework would enable the Fed to pursue its long-term inflation goal by providing more flexibility in how short-term inflation readings were reacted to.

Since the perceived “inflation deficit” from the decade after the financial crisis was over 8% at the end of 2020, which was highlighted in January’s annual letter, the rise in prices earlier this year was viewed favorably by Powell and most other Fed officials. After a decade of persistently below-target inflation, seeing prices rise at a rate above 2% for a time was a welcome sight within the halls of the Eccles building — even if it was caused by base-effects from last year’s shutdowns, and pandemic-induced bottlenecks in the economy that would presumably resolve themselves as time went on. Thus, as the year-over-year change in the headline Consumer Price Index rose above 2% in March, and above 4% in April, and then close to 5% in May, the dramatic policy response to the pandemic seemed not only to be providing extraordinary support to the economy, it was also creating significant progress toward alleviating the main policy dilemma of the last decade — persistently low inflation rates.

In the months since May, however, sentiment surrounding the rise in prices inside and outside the Federal Reserve has shifted markedly. Along with providing new flexibility to achieve its goal of 2% inflation over time, the new policy framework also represented an institutional effort by the Fed to put the ghosts of the 1970s behind it. The Second Great Mistake in Federal Reserve history was rooted in how monetary policy enabled the rising inflation of that era by succumbing to outside political pressure, and by letting the desire for short-term market stability override longer term goals. In the decades since then, falling rates of inflation made it much easier for the Fed to focus on its long-term goals — the Fed was generally not forced to choose between dampening rising inflation or attempting to stimulate the economy to increase employment.

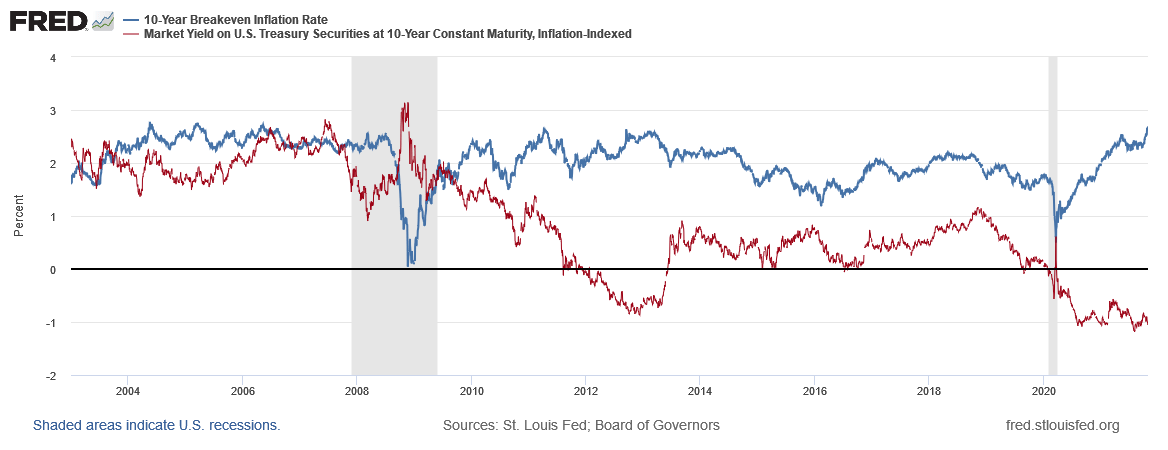

Over the last six months, however, prices have defied the Fed’s expectations and continued to rise at rates well above the 2% inflation target, and market estimates for inflation in the years ahead have recently risen to new highs (blue line above). Earlier this year, Fed officials expected prices to be moderating by the latter half of this year, and they certainly didn’t expect long-term inflation expectations to continue climbing further above 2% while employment remains lower than before the downturn, and well below what the Fed currently estimates would represent “full employment.”

This unwelcome combination of uncomfortably increasing inflation coupled with lower employment has been enough to reawaken the ghosts of the 1970s for many at the Fed. These fears are not often explicitly expressed by Fed officials in speeches and press conferences that represent the views of the rate-setting committee, but they can be clearly discerned from the change in tone in more informal settings. And over the past month, Chair Powell sent clear signals in his formal remarks that, in light of the stronger than anticipated rise in prices this year, it was time to act and begin reducing the $120 billion per month pace of the current quantitative easing program. This represents a fairly swift pivot for the Federal Reserve.

One of the conundrums amid these rapidly shifting inflation circumstances has been the persistence of ultra-low long-term bond yields. While inflation expectations have continued to rise in recent months, long-term Treasury bond yields have remained subdued. The entire Treasury yield curve remains below the Fed’s long-term inflation target of 2%, which means that the entire Treasury yield curve has a negative real yield relative to the rise in prices over the past year. The red line in the chart above highlights the 10-Year Inflation-Indexed Treasury yield, which remains near negative 1%. And the nominal 30-Year Treasury bond yield remains modestly below 2%, after trading as high as 2.5% earlier this year.

For many, the persistence of low long-term Treasury bond yields is a clear sign the market is anticipating the current inflation surge to eventually fade. Yet it may also be the case that long-term Treasury yields may not be reflecting the market’s expectations for inflation as much as assumed. As the past few years have clearly demonstrated, monetary policy is not solely focused on responding to inflation. A number of other factors have influenced short-term interest rate policy over the past decade, and some of those factors are now exerting a stronger influence than ever before. In a recent interview, a former markets desk trader at the New York Federal Reserve highlighted some of these factors, and his succinct and frank characterization of the dilemma facing monetary policy is worth reading in its entirety:

I think the Fed is really worried about inflation after telling everyone it was transitory – you no longer hear that word anymore. And I think it’s a really hard question for the Fed right now because a lot of this inflation, it appears to be driven by supply side effects. You have, you read about the energy crunch. We have congestion at ports. There is also a big demand burst as well. You know, we kind of printed and spent a lot of money and that increases demand. A lot of the supply constraints will be changed by interest rate hikes, but interest rate hikes do dampen demand. So if you hike rates, you can really hurt demand. And reducing demand, that lowers inflation. However, it costs your other mandate, which is full employment.

So, it’s a very, very difficult time for the Fed to choose right now. And I would also add that just mechanically speaking, looking at the financial system, it’s really hard for the Fed to hike rates without having a tremendous financial impact. And the reason for that is when you have a very high level of debt in the system, your interest rate hikes are magnified in their effect. So there’s interest rate risks in let’s say fixed income debt. And when you hike rates, you kind of basically destroy some of that value. And when you are thinking about Treasuries, you’re basically kind of pulling away money out of the system. If you think about Treasuries as a form of money, what we’ve been doing the past, let’s say decade, when we reduce rates, all those high-duration assets, their market price rises, they become enriched.

People have more money through that, which they can repo or sell, and then they can buy other stuff. Or if you’re, let’s say a 60/40 portfolio manager and your bonds appreciate, you will have to buy more equities to balance. Then that makes equity markets go higher. But when you’re hiking rates, you’re doing the reverse. And because the level of debt is so much higher, I think there’s some very long, non-linear impacts. So that collateral channel through which monetary policy is transmitted, that I think really sets a constraint on the Fed as to whether or not they can just hike rates like they did in the seventies, because you could have very, very large impacts on the financial markets.

– Joseph Wang, October 2021, Former Senior Markets Desk Trader at the New York Fed

When inflation rates rose in the late 1960s and 1970s, the Federal Reserve responded by increasing interest rates, but the increases were not enough to stem the rising tide of prices. The reasons the Fed failed to respond adequately are well documented, and we have discussed some of them in letters over the past few years — from the pressure Lyndon Johnson exerted on Fed Chair McChesney Martin to keep rates low amid the war in Vietnam, to Richard Nixon’s pressure on Fed Chair Arthur Burns to keep unemployment low in the run-up to the 1972 election, to the global imbalances which brought about an end to the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates. Monetary policy in the 1960s and 1970s was pressured by a number of forces outside the single issue of inflation, and the result was a more dramatic and lasting rise in prices than anyone anticipated when it began.

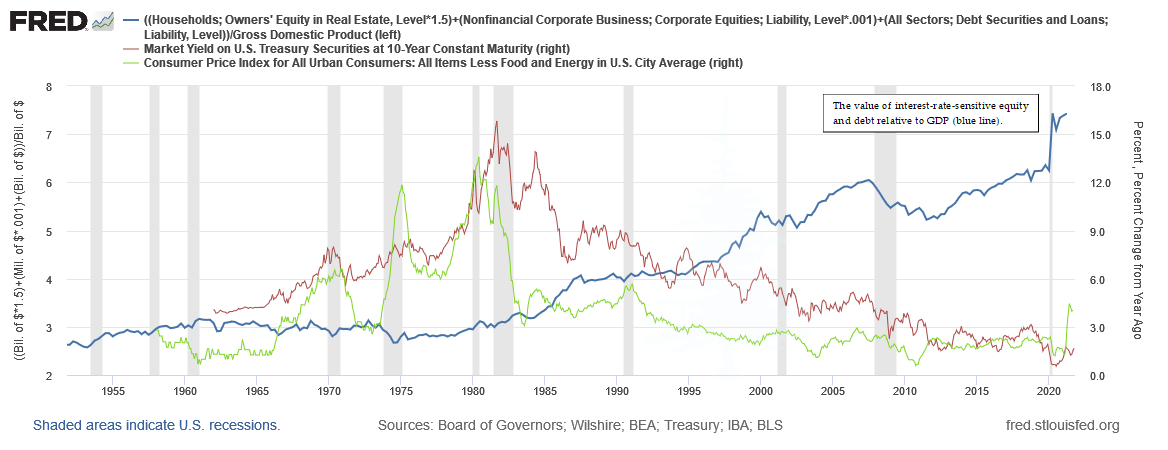

There are similarly strong forces outside inflation influencing monetary policy today. As Joseph Wang highlighted at the end of the passage above, the channel through which monetary policy is transmitted and magnified through the financial markets now represents a significant constraint on monetary policy. This can be seen in the chart below, where the blue line represents an estimate of the value of interest-rate-sensitive financial assets — including real estate, equity and debt — relative to the size of the economy. The value of these assets is now over 2.5 times what it was when the Fed attempted to raise rates in the 1960s and 1970s, and 25% higher than at the peak of the housing bubble fifteen years ago. This represents a powerful economic disincentive for higher interest rates.

The entrapment of monetary policy by debt and other factors that make responding to rising inflation problematic is part of what we have referred to in these letters as the Fed’s Third Great Mistake. And it may be the case that today’s low long-term bond yields are more of a reflection of this entrapment than a rational anticipation that the current high inflation readings will return to the low levels of the past decade. If so, many are misunderstanding the bond market’s signal.

As the 1940s clearly demonstrated, long-term interest rates can remain low if the market understands that the Fed will not raise short-term interest rates, despite high inflation. At that time, the Fed had an official agreement with the Treasury Department to keep short-term and long-term yields low while the federal government borrowed heavily for the war effort. There may not be such an explicit agreement today, but long-term bond yields may partially reflect a conclusion that the Fed will not be able to significantly increase interest rates for a long time — regardless of inflation.

The content of this document is provided as general information and is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment or other advice. This material is not to be construed as a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any security, financial product, instrument or to participate in any particular trading strategy. Not all securities, products or services described are available in all countries, and nothing herein constitutes an offer or solicitation of any securities, products or services in any jurisdiction where their offer or sale is not qualified or exempt from registration or otherwise legally permissible.

Although the material herein is based upon information considered reliable and up-to-date, Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC does not assure that this material is accurate, current, or complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. Content in this document may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted, in whole or in part, without prior written consent from Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC — which is usually gladly given, as long as its use includes clear and proper attribution. Contact us for more information.

© Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC

The Policy Repercussions of the Third Great Mistake Are Slowly Becoming More Apparent

By Brian McAuley

November 15, 2021

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said on Friday the U.S. central bank should begin reducing its asset purchases soon, but should not yet raise interest rates because employment is still too low and high inflation will likely abate next year as pressures from the COVID-19 pandemic fade.

“I do think it’s time to taper; I don’t think it’s time to raise rates,” Powell said in a virtual appearance before a conference. “We think we can be patient and allow the labor market to heal.” That outlook, Powell emphasized, is only the most likely case, adding that if inflation – already higher and lasting longer than earlier expected – moves persistently upward, the Fed would act.

The central bank, however, is facing a delicate balancing act in its dual mandate to seek full employment and stable prices. Consumer prices have been rising at more than twice the Fed’s 2% target, but employment is still well below the pre-pandemic level.

– Reuters, October 22, 2021

As much as last year centered around the Covid-19 pandemic and its impact on the economy, the major topic of discussion in the financial markets this year has been centered around inflation, and its prospective impact on monetary policy. During the first half of this year, Chair Jerome Powell and other Federal Reserve officials were consistently adamant that the increase in prices rippling through the economy was the result of transitory factors stemming from the pandemic itself and its direct impact on the economy’s ability to deliver goods and services efficiently. Since the rise in prices was attributed to causes which would dissipate over time as the economic impact of the pandemic waned, the Fed felt justified in more or less ignoring prices while focusing exclusively on the employment half of its dual mandate. And since there remained millions fewer people working than before the pandemic, the exclusive focus on employment seemed justified.

This approach was also in line with the Federal Reserve’s new policy framework, which was announced in August of last year. This new framework was the result of a critical assessment of the decade following the financial crisis, and the persistence of below-target inflation despite low interest rates and the first use of quantitative easing in seventy years. The assessment concluded that monetary policy had begun tightening prematurely under the assumption that inflation would revert to 2% over time as the effects of the financial crisis faded, when in fact inflation subsequently remained below 2%. This not only resulted in low inflation rates and low long-term Treasury yields later in the decade, it also severely limited the Federal Reserve’s room to maneuver in the event of another downturn in the economy, since short-term interest rates remained low. The new policy framework aimed to alleviate these circumstances by reframing the inflation half of the Fed’s dual mandate to aim for an average 2% inflation rate over time, instead of maintaining a 2% ceiling. This new framework would enable the Fed to pursue its long-term inflation goal by providing more flexibility in how short-term inflation readings were reacted to.

Since the perceived “inflation deficit” from the decade after the financial crisis was over 8% at the end of 2020, which was highlighted in January’s annual letter, the rise in prices earlier this year was viewed favorably by Powell and most other Fed officials. After a decade of persistently below-target inflation, seeing prices rise at a rate above 2% for a time was a welcome sight within the halls of the Eccles building — even if it was caused by base-effects from last year’s shutdowns, and pandemic-induced bottlenecks in the economy that would presumably resolve themselves as time went on. Thus, as the year-over-year change in the headline Consumer Price Index rose above 2% in March, and above 4% in April, and then close to 5% in May, the dramatic policy response to the pandemic seemed not only to be providing extraordinary support to the economy, it was also creating significant progress toward alleviating the main policy dilemma of the last decade — persistently low inflation rates.

In the months since May, however, sentiment surrounding the rise in prices inside and outside the Federal Reserve has shifted markedly. Along with providing new flexibility to achieve its goal of 2% inflation over time, the new policy framework also represented an institutional effort by the Fed to put the ghosts of the 1970s behind it. The Second Great Mistake in Federal Reserve history was rooted in how monetary policy enabled the rising inflation of that era by succumbing to outside political pressure, and by letting the desire for short-term market stability override longer term goals. In the decades since then, falling rates of inflation made it much easier for the Fed to focus on its long-term goals — the Fed was generally not forced to choose between dampening rising inflation or attempting to stimulate the economy to increase employment.

Over the last six months, however, prices have defied the Fed’s expectations and continued to rise at rates well above the 2% inflation target, and market estimates for inflation in the years ahead have recently risen to new highs (blue line above). Earlier this year, Fed officials expected prices to be moderating by the latter half of this year, and they certainly didn’t expect long-term inflation expectations to continue climbing further above 2% while employment remains lower than before the downturn, and well below what the Fed currently estimates would represent “full employment.”

This unwelcome combination of uncomfortably increasing inflation coupled with lower employment has been enough to reawaken the ghosts of the 1970s for many at the Fed. These fears are not often explicitly expressed by Fed officials in speeches and press conferences that represent the views of the rate-setting committee, but they can be clearly discerned from the change in tone in more informal settings. And over the past month, Chair Powell sent clear signals in his formal remarks that, in light of the stronger than anticipated rise in prices this year, it was time to act and begin reducing the $120 billion per month pace of the current quantitative easing program. This represents a fairly swift pivot for the Federal Reserve.

One of the conundrums amid these rapidly shifting inflation circumstances has been the persistence of ultra-low long-term bond yields. While inflation expectations have continued to rise in recent months, long-term Treasury bond yields have remained subdued. The entire Treasury yield curve remains below the Fed’s long-term inflation target of 2%, which means that the entire Treasury yield curve has a negative real yield relative to the rise in prices over the past year. The red line in the chart above highlights the 10-Year Inflation-Indexed Treasury yield, which remains near negative 1%. And the nominal 30-Year Treasury bond yield remains modestly below 2%, after trading as high as 2.5% earlier this year.

For many, the persistence of low long-term Treasury bond yields is a clear sign the market is anticipating the current inflation surge to eventually fade. Yet it may also be the case that long-term Treasury yields may not be reflecting the market’s expectations for inflation as much as assumed. As the past few years have clearly demonstrated, monetary policy is not solely focused on responding to inflation. A number of other factors have influenced short-term interest rate policy over the past decade, and some of those factors are now exerting a stronger influence than ever before. In a recent interview, a former markets desk trader at the New York Federal Reserve highlighted some of these factors, and his succinct and frank characterization of the dilemma facing monetary policy is worth reading in its entirety:

I think the Fed is really worried about inflation after telling everyone it was transitory – you no longer hear that word anymore. And I think it’s a really hard question for the Fed right now because a lot of this inflation, it appears to be driven by supply side effects. You have, you read about the energy crunch. We have congestion at ports. There is also a big demand burst as well. You know, we kind of printed and spent a lot of money and that increases demand. A lot of the supply constraints will be changed by interest rate hikes, but interest rate hikes do dampen demand. So if you hike rates, you can really hurt demand. And reducing demand, that lowers inflation. However, it costs your other mandate, which is full employment.

So, it’s a very, very difficult time for the Fed to choose right now. And I would also add that just mechanically speaking, looking at the financial system, it’s really hard for the Fed to hike rates without having a tremendous financial impact. And the reason for that is when you have a very high level of debt in the system, your interest rate hikes are magnified in their effect. So there’s interest rate risks in let’s say fixed income debt. And when you hike rates, you kind of basically destroy some of that value. And when you are thinking about Treasuries, you’re basically kind of pulling away money out of the system. If you think about Treasuries as a form of money, what we’ve been doing the past, let’s say decade, when we reduce rates, all those high-duration assets, their market price rises, they become enriched.

People have more money through that, which they can repo or sell, and then they can buy other stuff. Or if you’re, let’s say a 60/40 portfolio manager and your bonds appreciate, you will have to buy more equities to balance. Then that makes equity markets go higher. But when you’re hiking rates, you’re doing the reverse. And because the level of debt is so much higher, I think there’s some very long, non-linear impacts. So that collateral channel through which monetary policy is transmitted, that I think really sets a constraint on the Fed as to whether or not they can just hike rates like they did in the seventies, because you could have very, very large impacts on the financial markets.

– Joseph Wang, October 2021, Former Senior Markets Desk Trader at the New York Fed

When inflation rates rose in the late 1960s and 1970s, the Federal Reserve responded by increasing interest rates, but the increases were not enough to stem the rising tide of prices. The reasons the Fed failed to respond adequately are well documented, and we have discussed some of them in letters over the past few years — from the pressure Lyndon Johnson exerted on Fed Chair McChesney Martin to keep rates low amid the war in Vietnam, to Richard Nixon’s pressure on Fed Chair Arthur Burns to keep unemployment low in the run-up to the 1972 election, to the global imbalances which brought about an end to the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates. Monetary policy in the 1960s and 1970s was pressured by a number of forces outside the single issue of inflation, and the result was a more dramatic and lasting rise in prices than anyone anticipated when it began.

There are similarly strong forces outside inflation influencing monetary policy today. As Joseph Wang highlighted at the end of the passage above, the channel through which monetary policy is transmitted and magnified through the financial markets now represents a significant constraint on monetary policy. This can be seen in the chart below, where the blue line represents an estimate of the value of interest-rate-sensitive financial assets — including real estate, equity and debt — relative to the size of the economy. The value of these assets is now over 2.5 times what it was when the Fed attempted to raise rates in the 1960s and 1970s, and 25% higher than at the peak of the housing bubble fifteen years ago. This represents a powerful economic disincentive for higher interest rates.

The entrapment of monetary policy by debt and other factors that make responding to rising inflation problematic is part of what we have referred to in these letters as the Fed’s Third Great Mistake. And it may be the case that today’s low long-term bond yields are more of a reflection of this entrapment than a rational anticipation that the current high inflation readings will return to the low levels of the past decade. If so, many are misunderstanding the bond market’s signal.

As the 1940s clearly demonstrated, long-term interest rates can remain low if the market understands that the Fed will not raise short-term interest rates, despite high inflation. At that time, the Fed had an official agreement with the Treasury Department to keep short-term and long-term yields low while the federal government borrowed heavily for the war effort. There may not be such an explicit agreement today, but long-term bond yields may partially reflect a conclusion that the Fed will not be able to significantly increase interest rates for a long time — regardless of inflation.

The content of this document is provided as general information and is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment or other advice. This material is not to be construed as a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any security, financial product, instrument or to participate in any particular trading strategy. Not all securities, products or services described are available in all countries, and nothing herein constitutes an offer or solicitation of any securities, products or services in any jurisdiction where their offer or sale is not qualified or exempt from registration or otherwise legally permissible.

Although the material herein is based upon information considered reliable and up-to-date, Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC does not assure that this material is accurate, current, or complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. Content in this document may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted, in whole or in part, without prior written consent from Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC — which is usually gladly given, as long as its use includes clear and proper attribution. Contact us for more information.

© Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC

Investment Management

Before investing, we will discuss your goals and risk tolerances with you to see if a separately managed account at Sitka Pacific would be a good fit. To contact us for a free consultation, visit Getting Started.

Macro Value Monitor

To read a selection of recent client letters and be alerted when new letters are posted to our public site, visit Recent Client Letters.