The Greater Debasement Trade

4th Quarter, 2025

Beneath the surface of the short-term ups and downs of financial markets, a longer-term repricing of multiple assets may be underway as investors seek to protect themselves from the threats posed by runaway budget deficits.

While new rounds of tariff threats between the US and China sent traders from riskier assets and into bonds in recent days, money managers have been increasingly discussing a phenomenon known as the “debasement trade.”

~ Bloomberg, October 13, 2025

Rising downside risks to employment have shifted our assessment of the balance of risks. As a result, we judged it appropriate to take another step toward a more neutral policy stance at our September meeting. There is no risk-free path for policy as we navigate the tension between our employment and inflation goals…

~ Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, October 14, 2025

Since 2018, we have spent time in various articles discussing the transition in the late 1960s and early 1970s. This review has included detailing the pressure the Federal Reserve and monetary policy came under in the mid-1960s, as fiscal deficits spiraled higher. We have also reviewed the progression in the markets during those years as bond yields and inflation began to rise, and international pressure on the dollar increased — which eventually resulted in a break from gold in 1971. In the subsequent scramble for investments that would hold their value as the dollar began to devalue in the early 1970s, the price of gold began to rise, and the Nifty Fifty stock market bubble inflated.

As pivotal as that era was, the transition from low and stable inflation to higher and rising inflation in the 1960s and early 1970s took more than a decade to unfold. The evolution of investor sentiment took even longer; in fact, in some ways investor sentiment continues to evolve to this day.

While conversations about inflation ten years ago tended to refer to specific periods of high inflation, more recently such conversations have drifted more toward a general discussion of ongoing devaluation as a part of the investment landscape going forward. In light of the history of the dollar’s value since the 1960s, this is an appropriate, if rather belated, step in the evolution of investor sentiment.

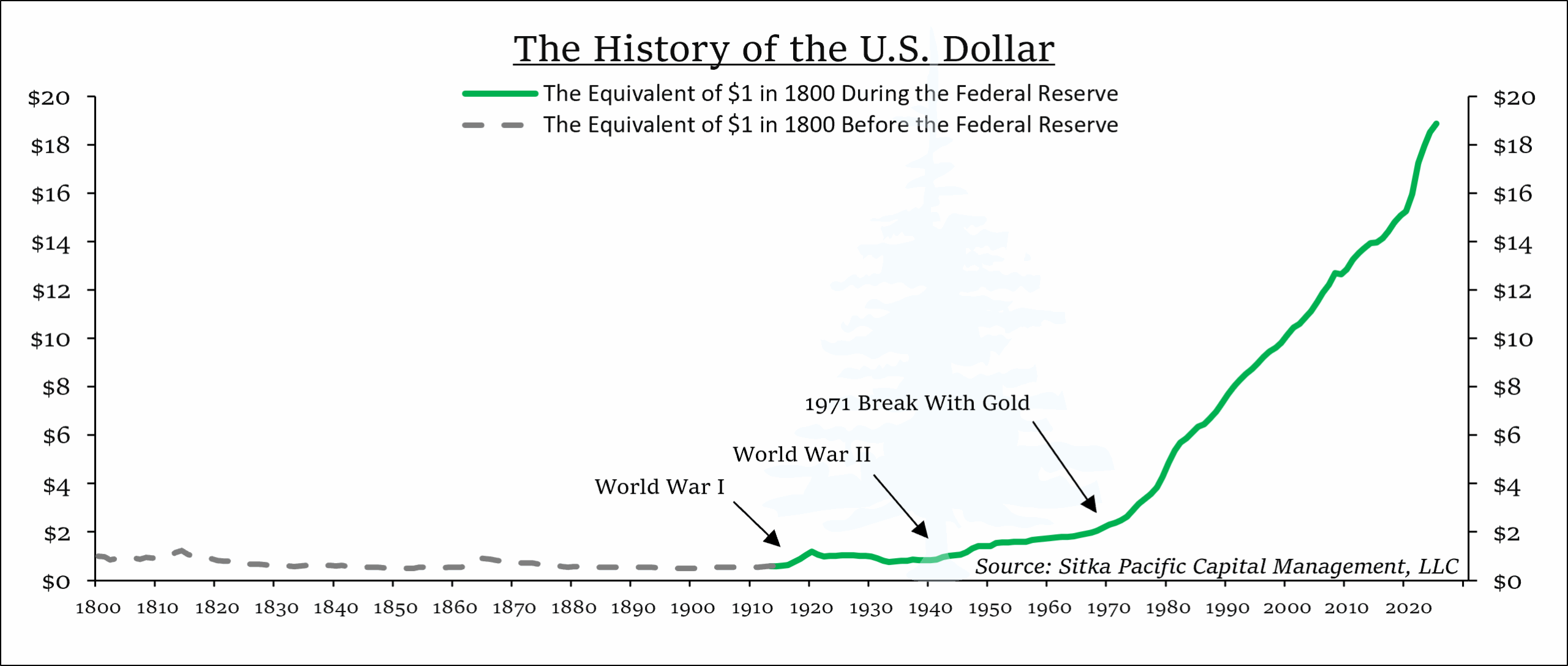

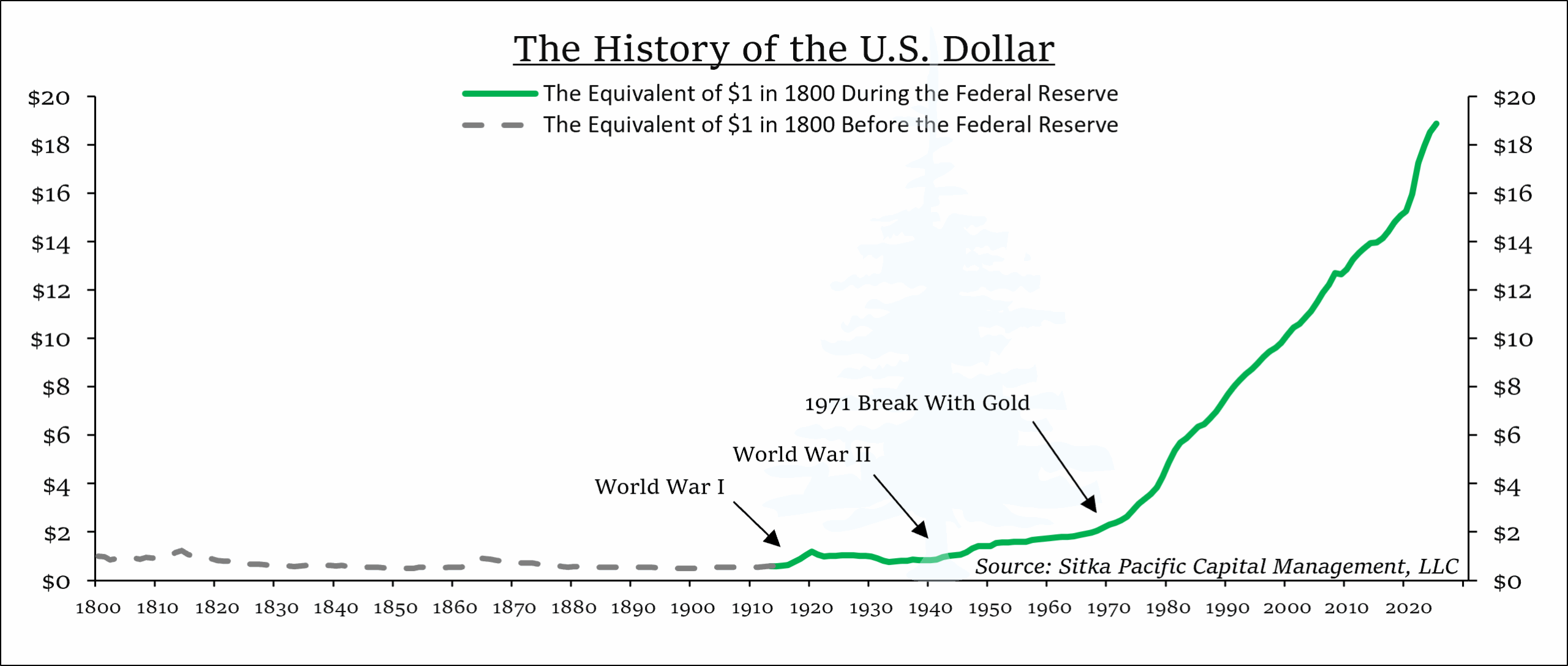

As can be seen above, continuous devaluation has not always been a feature of our currency. As recently as the onset of World War II, the value of the dollar remained relatively stable. According to consumer price data from the Minneapolis branch of the Federal Reserve, one U.S. dollar purchased about the same value of goods when Pearl Harbor was attacked on December 7, 1941, as it did when John Adams was president in 1800. Though there were deflationary ups and inflationary downs in the dollar’s value over the course of the intervening 142 years, the value of the dollar remained stable over the long term.

Since World War II, however, the erosion of the dollar’s value has been continuous. Today, it takes about $19 to purchase what $1 purchased in 1941.

While most of that loss of value occurred after the 1950s, the foundation for the pivot of the dollar’s value was set between 1918 and the1940s. The first cornerstones were laid by the actions of the Federal Reserve during World War I, by President Roosevelt during the early 1930s, and by the subsequent takeover of the Federal Reserve by the Treasury Department in 1942. These cornerstones enabled the federal government to borrow as much as it needed to win two world wars. The foundation was then reinforced by the decision to maintain control of the Federal Reserve after World War II ended, to prevent a repeat of the post-WWI deflation in the early 1920s.

Together, these precedents established a conditional independence for the Federal Reserve: monetary policy would remain independent only until such time that the government needed monetary policy to be subservient to fiscal priorities.

Since then, this conditional independence of monetary policy has provided an implicit permission for the federal government to borrow as much as it needs to, since the Federal Reserve, though it ostensibly regained its independence with the Treasury-Fed Accord in 1951, can be counted on to intervene and moderate the market consequences from that borrowing. More than any other factor in the eighty years since the end of the war, this implicit permission stemming from the Fed’s conditional independence has been responsible for the continuous erosion of the dollar’s value. It is also responsible for some market trends which can appear counter-intuitive at first glance.

We witnessed this implied permission in action most recently in 2020 and 2021. Although the Federal Reserve had just started to reduce its post–Financial Crisis balance sheet expansion, the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic prompted the Fed to quickly shelve its normalization plans. Instead, the Fed doubled the base money supply over the following two years, which enabled the federal government to issue $7 trillion in debt at the lowest rates in history. As with the response to the financial crisis a decade earlier, had the Federal Reserve not acted independently to facilitate the federal government’s response, it may well have been forced to act as it was during World War II.

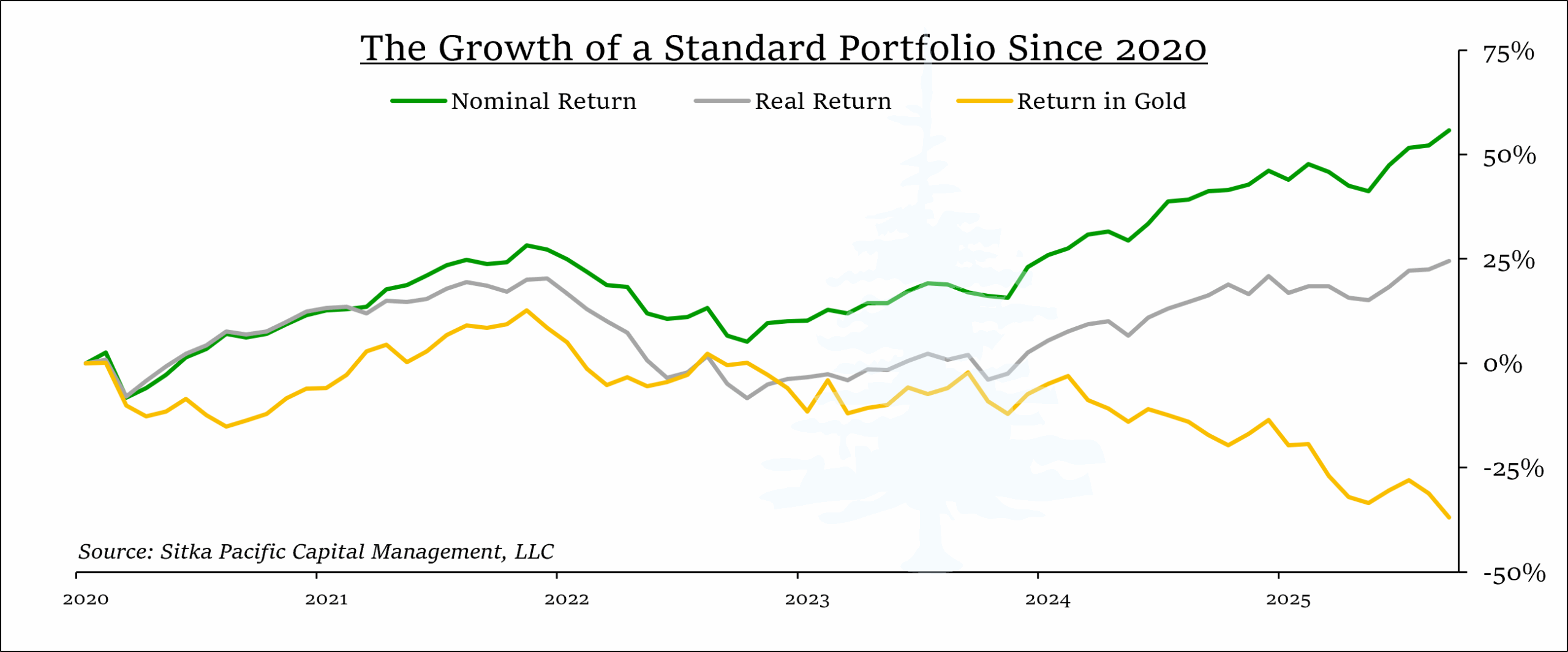

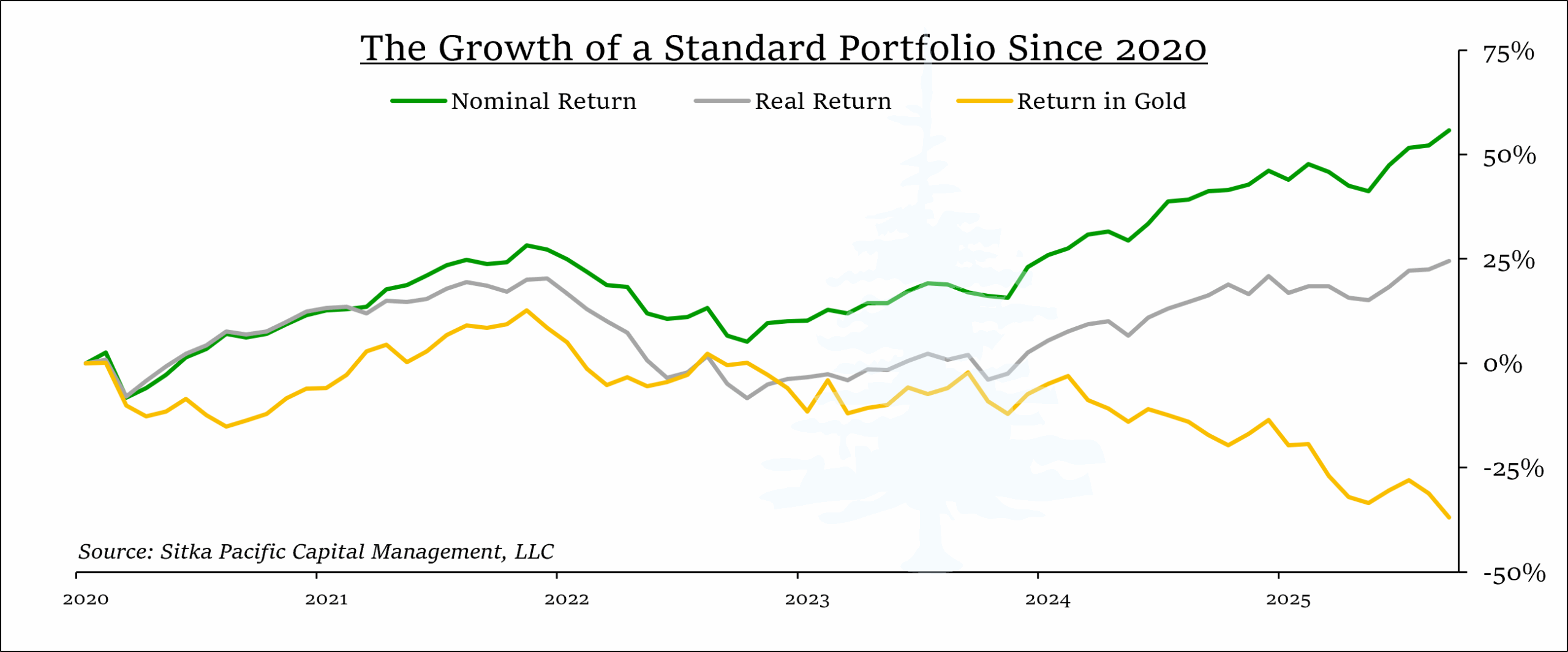

Today, we are still navigating the market impact of those actions. Although there have been nominal gains in a Standard Portfolio of stocks and bonds since 2020, those nominal returns over the past five years have been somewhat of an illusion. This stems from the 25% erosion in value of the dollar since 2020, which has imparted what some economists have coined a money illusion.

We can see the impact of the money illusion on the value of stocks and bonds over the past five years. While a portfolio of 60% stocks and 40% bonds has returned 9.3% annually from 2020 through the third quarter of 2025, about half of that nominal return has been eroded by the change in the dollar’s value. When the impact of this inflation is taken into account, the resulting real return of a portfolio of stocks and bonds has been 4.6% annually.

Since gold is sensitive to changes in monetary conditions long before they impact consumer prices, the decline of stocks and bonds versus gold shown in the chart above is indicative of the strong influence monetary policy has had on the markets in recent years.

The illusory nature of returns over the past five years, shown in the chart above, is similar to what unfolded in the 1960s and early 1970s, shown in the chart below.

During the early years of The Great Inflation, federal deficits expanded and the rate of inflation began to rise, just as they have in recent years. In response to rising inflation, bond yields began to rise, and the dollar came under increasing pressure – just has they have recently. After the break away from gold in 1971, the dollar began to decline precipitously against other currencies, the price of gold began to rise, and the Nifty Fifty bubble inflated as investors herded into stocks which were thought to be inflation-proof.

The progression of the events in the late 1960s through the peak of the Nifty Fifty bubble in 1973 is remarkably similar to the market environment in recent years, and this similarity is part of the reason we have spent time reviewing that era. If we replace Nifty Fifty with The Magnificent Seven in the chart above, it would be nearly identical to the progression of the markets since 2020, marked by strong nominal returns, modest real returns, and losses versus gold.

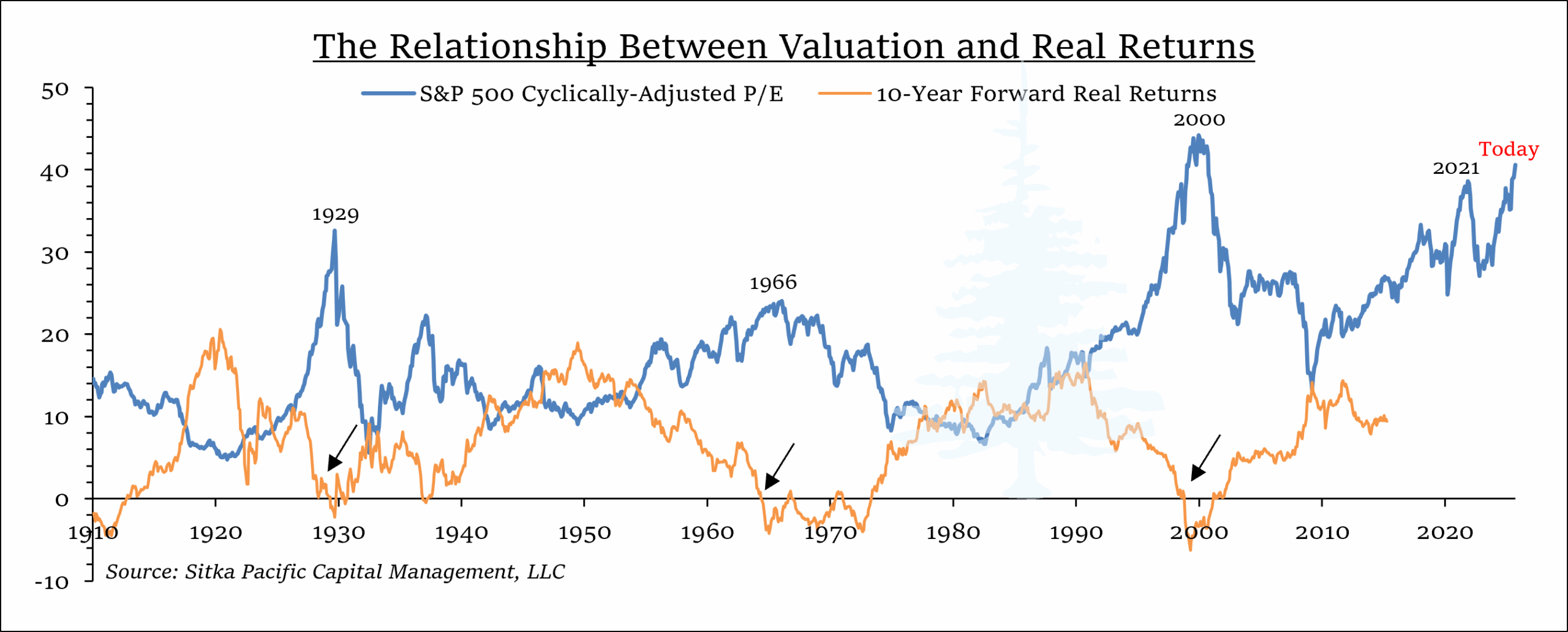

There have been other indications of monetary policy’s inflationary impact on the markets as well. The sole driver of the nominal return in a standard portfolio of stocks and bonds over the past five years has been from stocks, and the return from stocks has primarily come from an expansion of valuation. In fact, approximately 60% of the return from stocks this decade has come from a rise in the market’s valuation, not the underlying value growth of the businesses.

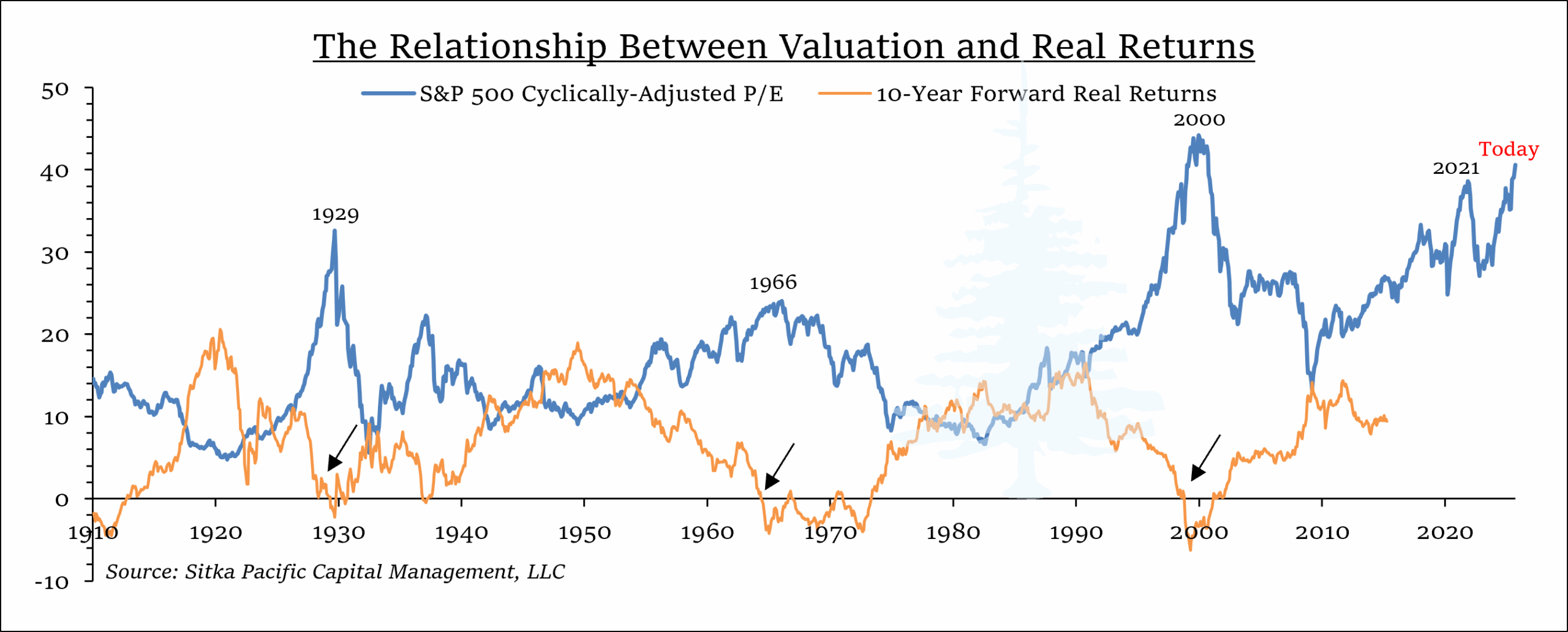

As can be seen in the chart below, the market’s valuation expansion has taken the S&P 500’s Cyclically Adjusted Price-to-Earnings Ratio (CAPE) to the second highest level in history. The only other time this valuation measure has been higher was at the very peak of the Tech Bubble in 1999 and 2000.

Without the expansion of the equity market’s valuation, a portfolio stocks and bonds would have returned less than it has since 2020. For example, if the S&P 500 were trading today at the same valuation as it was at the start of the decade, the annualized gain of a Standard Portfolio would have been 6.5% over the past five years, and its real return would have been just 1.4%. Taken together, the equity market’s rising valuation and inflation account for 87% of the Standard Portfolio’s return over the past five years.

Understanding where returns come from is important, as valuations do not rise indefinitely over time. Returns from a rise in valuation far above its long-term average are inevitably clawed back when valuations subsequently revert. On the chart above, black arrows highlight the beginning of past periods of clawing back returns, as valuations reverted.

Unless the rise of AI has delivered the market onto the mythical permanently high plateau economist Irving Fisher envisioned in October 1929, a similar era of reversion will follow the current period of elevated valuations. During that time, returns from rising valuations will be clawed back, just as they were in the 1930s, 1970s, and 2000s.

* * *

Throughout the year, there has been a lively discussion of the so called Debasement Trade of 2025.

While the trade-weighted U.S. Dollar Index fell 10% through the third quarter, the Debasement Trade discussion centered around policy events which may have weakened the long-term outlook for the dollar. The passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill in July was one such event, as it cemented and increased the projected federal deficit over the next decade. Other events include the return to 19th century–style tariff policies, which prompted foreign holders of dollar assets to begin hedging their currency exposure, as well as attacks directed toward the Federal Reserve. These attacks have drawn into question just how independent monetary policy in the U.S. will be in the years to come.

The weakened outlook has kindled speculation that the decline in the value of the dollar this year may be only the beginning of a long-term erosion of dollar strength. Although it now takes $19 to buy what $1 could buy at the start of World War II, this year has the potential to mark a moment when the markets began pricing in a greater debasement. It is in this context that the price of gold has risen over 50%, and equity markets outside the U.S. outperformed by the widest margin in over a decade. The theme underlying all of these trends is the expectation of further dollar weakness, not just this year, or next, but for many years to come.

Cycles of valuation, currency regimes, and interest rates tend to unfold over the course of many years. Initial bursts of outperformance by gold and equity markets outside the U.S. in both the early 2000s and the early 1970s marked the beginning of decade-long trends, and the value of being widely diversified among asset classes, regions, currencies, as well as factors and styles was substantial during those periods.

The benefits of global diversification have been substantial in 2025 as well. The Greater Debasement Trade, that of remaining globally diversified in preparation for a long-term erosion of dollar value, appears poised to provide real benefits for years to come.

The content of this article is provided as general information and is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment or other advice. This material is not to be construed as a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any security, financial product, instrument or to participate in any particular trading strategy. Not all securities, products or services described are available in all countries, and nothing herein constitutes an offer or solicitation of any securities, products or services in any jurisdiction where their offer or sale is not qualified or exempt from registration or otherwise legally permissible.

Although the material herein is based upon information considered reliable and up-to-date, Sitka Pacific Capital Management, LLC does not assure that this material is accurate, current, or complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. Content in this article may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted, in whole or in part, without prior written consent — which is usually gladly given, as long as its use includes clear and proper attribution. Contact us for more information.

© Sitka Pacific Capital Management, LLC

The Greater Debasement Trade

4th Quarter, 2025

Beneath the surface of the short-term ups and downs of financial markets, a longer-term repricing of multiple assets may be underway as investors seek to protect themselves from the threats posed by runaway budget deficits.

While new rounds of tariff threats between the US and China sent traders from riskier assets and into bonds in recent days, money managers have been increasingly discussing a phenomenon known as the “debasement trade.”

~ Bloomberg, October 13, 2025

Rising downside risks to employment have shifted our assessment of the balance of risks. As a result, we judged it appropriate to take another step toward a more neutral policy stance at our September meeting. There is no risk-free path for policy as we navigate the tension between our employment and inflation goals…

~ Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, October 14, 2025

Since 2018, we have spent time in various articles discussing the transition in the late 1960s and early 1970s. This review has included detailing the pressure the Federal Reserve and monetary policy came under in the mid-1960s, as fiscal deficits spiraled higher. We have also reviewed the progression in the markets during those years as bond yields and inflation began to rise, and international pressure on the dollar increased — which eventually resulted in a break from gold in 1971. In the subsequent scramble for investments that would hold their value as the dollar began to devalue in the early 1970s, the price of gold began to rise, and the Nifty Fifty stock market bubble inflated.

As pivotal as that era was, the transition from low and stable inflation to higher and rising inflation in the 1960s and early 1970s took more than a decade to unfold. The evolution of investor sentiment took even longer; in fact, in some ways investor sentiment continues to evolve to this day.

While conversations about inflation ten years ago tended to refer to specific periods of high inflation, more recently such conversations have drifted more toward a general discussion of ongoing devaluation as a part of the investment landscape going forward. In light of the history of the dollar’s value since the 1960s, this is an appropriate, if rather belated, step in the evolution of investor sentiment.

As can be seen above, continuous devaluation has not always been a feature of our currency. As recently as the onset of World War II, the value of the dollar remained relatively stable. According to consumer price data from the Minneapolis branch of the Federal Reserve, one U.S. dollar purchased about the same value of goods when Pearl Harbor was attacked on December 7, 1941, as it did when John Adams was president in 1800. Though there were deflationary ups and inflationary downs in the dollar’s value over the course of the intervening 142 years, the value of the dollar remained stable over the long term.

Since World War II, however, the erosion of the dollar’s value has been continuous. Today, it takes about $19 to purchase what $1 purchased in 1941.

While most of that loss of value occurred after the 1950s, the foundation for the pivot of the dollar’s value was set between 1918 and the1940s. The first cornerstones were laid by the actions of the Federal Reserve during World War I, by President Roosevelt during the early 1930s, and by the subsequent takeover of the Federal Reserve by the Treasury Department in 1942. These cornerstones enabled the federal government to borrow as much as it needed to win two world wars. The foundation was then reinforced by the decision to maintain control of the Federal Reserve after World War II ended, to prevent a repeat of the post-WWI deflation in the early 1920s.

Together, these precedents established a conditional independence for the Federal Reserve: monetary policy would remain independent only until such time that the government needed monetary policy to be subservient to fiscal priorities.

Since then, this conditional independence of monetary policy has provided an implicit permission for the federal government to borrow as much as it needs to, since the Federal Reserve, though it ostensibly regained its independence with the Treasury-Fed Accord in 1951, can be counted on to intervene and moderate the market consequences from that borrowing. More than any other factor in the eighty years since the end of the war, this implicit permission stemming from the Fed’s conditional independence has been responsible for the continuous erosion of the dollar’s value. It is also responsible for some market trends which can appear counter-intuitive at first glance.

We witnessed this implied permission in action most recently in 2020 and 2021. Although the Federal Reserve had just started to reduce its post–Financial Crisis balance sheet expansion, the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic prompted the Fed to quickly shelve its normalization plans. Instead, the Fed doubled the base money supply over the following two years, which enabled the federal government to issue $7 trillion in debt at the lowest rates in history. As with the response to the financial crisis a decade earlier, had the Federal Reserve not acted independently to facilitate the federal government’s response, it may well have been forced to act as it was during World War II.

Today, we are still navigating the market impact of those actions. Although there have been nominal gains in a Standard Portfolio of stocks and bonds since 2020, those nominal returns over the past five years have been somewhat of an illusion. This stems from the 25% erosion in value of the dollar since 2020, which has imparted what some economists have coined a money illusion.

We can see the impact of the money illusion on the value of stocks and bonds over the past five years. While a portfolio of 60% stocks and 40% bonds has returned 9.3% annually from 2020 through the third quarter of 2025, about half of that nominal return has been eroded by the change in the dollar’s value. When the impact of this inflation is taken into account, the resulting real return of a portfolio of stocks and bonds has been 4.6% annually.

Since gold is sensitive to changes in monetary conditions long before they impact consumer prices, the decline of stocks and bonds versus gold shown in the chart above is indicative of the strong influence monetary policy has had on the markets in recent years.

The illusory nature of returns over the past five years, shown in the chart above, is similar to what unfolded in the 1960s and early 1970s, shown in the chart below.

During the early years of The Great Inflation, federal deficits expanded and the rate of inflation began to rise, just as they have in recent years. In response to rising inflation, bond yields began to rise, and the dollar came under increasing pressure – just has they have recently. After the break away from gold in 1971, the dollar began to decline precipitously against other currencies, the price of gold began to rise, and the Nifty Fifty bubble inflated as investors herded into stocks which were thought to be inflation-proof.

The progression of the events in the late 1960s through the peak of the Nifty Fifty bubble in 1973 is remarkably similar to the market environment in recent years, and this similarity is part of the reason we have spent time reviewing that era. If we replace Nifty Fifty with The Magnificent Seven in the chart above, it would be nearly identical to the progression of the markets since 2020, marked by strong nominal returns, modest real returns, and losses versus gold.

There have been other indications of monetary policy’s inflationary impact on the markets as well. The sole driver of the nominal return in a standard portfolio of stocks and bonds over the past five years has been from stocks, and the return from stocks has primarily come from an expansion of valuation. In fact, approximately 60% of the return from stocks this decade has come from a rise in the market’s valuation, not the underlying value growth of the businesses.

As can be seen in the chart below, the market’s valuation expansion has taken the S&P 500’s Cyclically Adjusted Price-to-Earnings Ratio (CAPE) to the second highest level in history. The only other time this valuation measure has been higher was at the very peak of the Tech Bubble in 1999 and 2000.

Without the expansion of the equity market’s valuation, a portfolio stocks and bonds would have returned less than it has since 2020. For example, if the S&P 500 were trading today at the same valuation as it was at the start of the decade, the annualized gain of a Standard Portfolio would have been 6.5% over the past five years, and its real return would have been just 1.4%. Taken together, the equity market’s rising valuation and inflation account for 87% of the Standard Portfolio’s return over the past five years.

Understanding where returns come from is important, as valuations do not rise indefinitely over time. Returns from a rise in valuation far above its long-term average are inevitably clawed back when valuations subsequently revert. On the chart above, black arrows highlight the beginning of past periods of clawing back returns, as valuations reverted.

Unless the rise of AI has delivered the market onto the mythical permanently high plateau economist Irving Fisher envisioned in October 1929, a similar era of reversion will follow the current period of elevated valuations. During that time, returns from rising valuations will be clawed back, just as they were in the 1930s, 1970s, and 2000s.

* * *

Throughout the year, there has been a lively discussion of the so called Debasement Trade of 2025.

While the trade-weighted U.S. Dollar Index fell 10% through the third quarter, the Debasement Trade discussion centered around policy events which may have weakened the long-term outlook for the dollar. The passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill in July was one such event, as it cemented and increased the projected federal deficit over the next decade. Other events include the return to 19th century–style tariff policies, which prompted foreign holders of dollar assets to begin hedging their currency exposure, as well as attacks directed toward the Federal Reserve. These attacks have drawn into question just how independent monetary policy in the U.S. will be in the years to come.

The weakened outlook has kindled speculation that the decline in the value of the dollar this year may be only the beginning of a long-term erosion of dollar strength. Although it now takes $19 to buy what $1 could buy at the start of World War II, this year has the potential to mark a moment when the markets began pricing in a greater debasement. It is in this context that the price of gold has risen over 50%, and equity markets outside the U.S. outperformed by the widest margin in over a decade. The theme underlying all of these trends is the expectation of further dollar weakness, not just this year, or next, but for many years to come.

Cycles of valuation, currency regimes, and interest rates tend to unfold over the course of many years. Initial bursts of outperformance by gold and equity markets outside the U.S. in both the early 2000s and the early 1970s marked the beginning of decade-long trends, and the value of being widely diversified among asset classes, regions, currencies, as well as factors and styles was substantial during those periods.

The benefits of global diversification have been substantial in 2025 as well. The Greater Debasement Trade, that of remaining globally diversified in preparation for a long-term erosion of dollar value, appears poised to provide real benefits for years to come.

The content of this article is provided as general information and is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment or other advice. This material is not to be construed as a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any security, financial product, instrument or to participate in any particular trading strategy. Not all securities, products or services described are available in all countries, and nothing herein constitutes an offer or solicitation of any securities, products or services in any jurisdiction where their offer or sale is not qualified or exempt from registration or otherwise legally permissible.

Although the material herein is based upon information considered reliable and up-to-date, Sitka Pacific Capital Management, LLC does not assure that this material is accurate, current, or complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. Content in this article may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted, in whole or in part, without prior written consent — which is usually gladly given, as long as its use includes clear and proper attribution. Contact us for more information.

© Sitka Pacific Capital Management, LLC

Investment Management

Before investing, we will discuss your goals and risk tolerances with you to see if a separately managed account at Sitka Pacific would be a good fit. To contact us for a free consultation, visit Getting Started.

Macro Value Monitor

To read a selection of recent client letters and be alerted when new letters are posted to our public site, visit Recent Client Letters.