Kipper und Wipperzeit

January 31, 2023

It must all go to wrack and ruin, it cannot last for long, for it is now the devil’s work, and it will spawn a noble brood:

Clippers and whippers they are called, and thought to show great intelligence. Although it’s but the devil’s trick, they think it’s a masterpiece, whereby, beneath the guise of right, they rob the poor of all they possess.

These godless folks have as their aim, in daytime and as well as night, to ruin the poor, and do not spare, whatever they’ve set in their sight…

~ Translated from an early 17th century German broadsheet

Early in the morning on Tuesday, May 23, in the year 1618, four Catholic lords entered the Bohemian Chancellory in Hradčany Castle, just west of the Vltava River in Prague. They proceeded directly to the main meeting hall, where they began preparing for the imminent arrival of the Protestant members of the recently dissolved Bohemian Assembly.

The Protestant lords were descending on Hradčany Castle that morning to learn whether the Catholic lords had a hand in persuading the new King of Bohemia, Ferdinand of Styria, to order the cessation of construction of Protestant churches on royal land. Although Habsburg emperors had been increasing Protestant rights and freedoms throughout the Holy Roman Empire, including the right to build Protestant churches on royal land, Ferdinand was a proponent of the Catholic Counter-Reformation. Upon his ascension to Bohemia’s throne in 1617, construction of Protestant churches on royal land in Bohemia had been halted. When the Protestant members of the Bohemian Assembly protested this infringement on their new rights, the new king responded by dissolving the Assembly. Incensed, the lords of Bohemia’s three main Protestant estates were demanding answers – and they arrived at the Chancellory meeting hall promptly at 9 a.m. to get them.

As the meeting commenced, Protestant Lord Paul Rziczan addressed the gathered members and described the contents of a letter they had received from the king, which had condemned the Protestant members of the Assembly, before directing his inquiry to the four Catholic lords present in the meeting hall:

His Imperial Majesty had sent to their graces the lord regents a sharp letter that was, by our request, issued to us as a copy after the original had been read aloud, and in which His Majesty declared all of our lives and honour already forfeit, thereby greatly frightening all three Protestant estates. As they also absolutely intended to proceed with the execution against us, we came to a unanimous agreement among ourselves that, regardless of any loss of life and limb, honour and property, we would stand firm, with all for one and one for all … nor would we be subservient, but rather we would loyally help and protect each other to the utmost, against all difficulties. Because, however, it is clear that such a letter came about through the advice of some of our religious enemies, we wish to know, and hereby ask the lord regents present, if all or some of them knew of the letter, recommended it, and approved of it.

Upon hearing this accusation of conspiracy against the Protestant lords, the Catholic lords requested leave to seek the counsel of their leader, who was not present in the Chancellory that morning, before giving the full Assembly their response. But the Protestant lords refused to allow them out of their sights – they demanded an immediate answer.

Two of the Catholic lords, Adam II von Sternberg and Matthew Leopold Popel Lobkowitz, were found innocent in the ensuing interrogation, after being vouched for by their fellow Protestant assemblymen. Their piety and devotion made such a conspiracy with the king seem beyond their capability. They were removed from the meeting hall, with Adam II von Sternberg vehemently declaring as he left that they had never advised anything impinging on established Protestant rights.

The remaining two Catholic lords – Count Vilem Slavata of Chlum, and Count Jaroslav Bořita of Martinice – were known Catholic hardliners and supporters of the new king. Under further questioning they eventually admitted their role in the king’s letter condemning the Protestant lords, and told the gathered Assembly they would gladly accept being arrested and imprisoned for such a worthy Catholic cause.

The Protestant lords had other ideas. One of them, Count von Thurn, turned to Slavata and Bořita and said:

“You are enemies of us and of our religion, have desired to deprive us of our [rights], have horribly plagued your Protestant subjects … and have tried to force them to adopt your religion against their wills or have had them expelled for this reason.” Then, addressing the entire Assembly, he declared: “Were we to keep these men alive, then we would lose [our rights] and our religion … for there can be no justice to be gained from or by them.”

The incited Protestant lords then rose up and proceeded to throw Slavata, Bořita and their attending scribe out of the top floor windows of the castle tower, where they plummeted seventy feet to the ground below.

Miraculously, they survived.

According to Catholic legend, they were caught in mid-air by angels, or possibly by the Virgin Mary herself, and then settled gently upon the ground. According to the Protestant pamphlets which circulated throughout Bohemia shortly afterward, they survived by landing on a soft mound of dung at the base of the tower; which may have been more of a metaphorical retort than a claim of literal fact.

Either by angels or by dung, real or otherwise, the two Catholic lords and their faithful scribe fled Prague alive, and as news of the defenestration spread, Catholic and Protestant realms throughout the Holy Roman Empire began preparing for war.

* * *

Albrecht Eusebius Wenzel von Wallenstein was born into modest means, by noble standards, but the same would not be said of his ambition. His parents, father Vilém and mother Markéta, welcomed him into the world on September 24, 1583, in Heřmanice, Bohemia, in modern-day Czech Republic. This was then the largest and easternmost province of the Holy Roman Empire. Though his parents were relatively poor, they belonged to a branch of the Waldstein family, which owned Heřmanice Castle and seven surrounding villages. And being part of the old aristocracy, they were connected with some of the wealthiest families in Bohemia.

Young Wallenstein was raised by his uncle Heinrish Slawata von Chlum after both of his parents had passed away by 1595. His uncle sent him first to the school of the Bohemian Brothers in Koschumberg, and then in 1597 to the Protestant school at Goldberg, in Silesia. In 1599 he enrolled at the Protestant Academy in Altof, near Nuremberg, Franconia, but the following year was dismissed on account of brawling and épée fighting, which also landed him in prison.

Upon his release from prison, Wallenstein served as a page at the court of Margrave Karl of Burgau, in Innsbruck, where he also survived a long fall from a high window – an event which seems to mark a number of pivotal moments in European history. Though it is unknown whether he fell or was thrown out the window, it is known that he converted to Catholicism shortly afterwards; a contemporary of Wallenstein’s, Franz Christoph von Khevenhüller, credited the Virgin Mary with saving his life during his fall. Yet however divinely inspired it was, his conversion also furthered to his ambition to climb the social ladder and serve in higher offices in the Counter-Reformation-minded Habsburg courts.

In the years that followed his brief time in Innsbruck, and his fall from the window, Wallenstein traveled throughout the Holy Roman Empire, Holland, France and Italy, where he stayed at the universities of Bologna and Padua, studying astrology and military tactics. Italy made a strong impression on him, an impression that would be infused into his estates in later years, and he became fluent in Latin and Italian, along with his native German and Czech. He also learned French and Spanish. Upon returning to Bohemia in 1604, he served in the Imperial Army in Hungary for two years, fighting the Turks and the Protestant Hungarians – where he distinguished himself.

Yet it was 1609 that brought the most important event that shaped young Wallenstein’s life, and it happened not on a battlefield, nor at a far-off university. That year he married Lucretia Nekesch von Landek, the very rich Moravian widow of Arkleb of Víckov, who owned the towns of Vsetín, Lukov, Rymice and Všetuly/Holešoy, and surrounding villages. Although the marriage was destined to be brief, as Lucretia died shortly thereafter in 1614, it provided Wallenstein with a vast estate upon her passing. This inheritance, along with the estate he inherited from his uncle Heinrish, had made Wallenstein, at the age of just thirty-one, one of the wealthiest noblemen in Bohemia.

Albrecht Eusebius Wenzel von Wallenstein Portrait by Anthony Van Dyck, 1629

Not wasting any time, the ambitious Wallenstein immediately proceeded to use his vast wealth to increase and solidify his position in the Habsburg court. In 1617, the new King of Bohemia, Ferdinand of Styria, who would the following year end construction of Protestant churches on royal land in Bohemia and then dissolve the Bohemian Assembly after the Protestant lords protested, waged war on Venice. Wallenstein immediately sent troops at his own expense to aid the king, and led them himself. He and his two hundred mounted troops relieved the fortress of Gradisca in northern Italy from a Venetian siege, where he again distinguished himself bravely in battle.

When the Catholic nobels and their scribe were thrown from the tower windows of Hradčany Castle in Prague the following spring, it marked the beginning of one of the most destructive conflicts in European history – the Thirty Years’ War. After the Catholic lords fled Prague, Count von Thurn, the Protestant lord who had led the questioning of the four Catholic lords in the meeting of the dissolved Assembly and incited the defenestration, formed a rival government and raised an army to challenge Ferdinand for the throne of Bohemia. The Protestant estates of Bohemia successfully deposed Ferdinand in August. However, two days after Ferdinand was deposed as King of Bohemia, he was elected Holy Roman Emperor, and as emperor he eventually reclaimed Bohemia and Prague for the Catholic Habsburgs after the Battle of White Mountain on November 8, 1620.

Although the Battle of White Mountain was only the first major battle of the long Thirty Years’ War, the Habsburgs entered the conflict financially exhausted. They had no standing army in 1618, and after King Ferdinand was deposed in Bohemia, they had pleaded for financial aid from abroad and had, in desperation, contracted mercenaries to face Count von Thurn’s armies. But Emperor Ferdinand could not afford to pay the mercenaries’ salaries. He quickly needed a large sum of gold and silver, but there were no capital markets from which he could borrow, and levying new taxes was difficult and would take time – time the emperor did not have. Desperate times called for desperate measures, and to finance the recapture of Bohemia, the emperor had turned to Wallenstein.

Emperor Ferdinand agreed to lease control of all the mints of Bohemia, neighboring Moravia and Lower Austria to Wallenstein and a consortium of wealthy nobles in exchange for a supplying him with enough money to pay his armies. The deal gave the emperor large guaranteed payments, which he desperately needed, in exchange for the opportunity for the consortium to profit from turning gold and silver into official currency. The consortium was granted the exclusive right to strike large and small coin denominations in those regions, with the purity of those gold and silver coins – the amount of gold and silver each coin denomination contained – having long been established by an Imperial Ordinance in place since 1559.

Wallenstein and the consortium, however, had seen a golden opportunity. A tremendous profit could be made if coins were minted with less gold and silver than specified, which would allow more coins to be made from the gold and silver the consortium had on hand. To this end, copper began to be mixed in with gold and silver to inflate the amount of raw alloy the mints had to strike official coins. The consortium delivered the copper-infused money to the emperor so he could pay his armies, and then sent agents to neighboring territories to exchange the copper-infused coins for coins that were pure gold and silver from unsuspecting merchants and peasants. These pure coins were brought back, melted down, and then the number multiplied by striking new copper-infused coins.

Wallenstein and the consortium reaped a tremendous profit from the mint operations, and it allowed him to increase his already vast wealth by leaps and bounds. As the emperor’s armies regained territory from the Protestants, Wallenstein claimed close to sixty estates in Bohemia, either by confiscating them directly, or by purchasing them with devalued, copper-infused money. The other nobles, many of whom remained anonymous, profited as well, but did not parlay their mint profits as shrewdly as Wallenstein. By the time of the consortium’s final mint contract in 1622, at the age of thirty-nine Wallenstein was funding his own armies and had become the most powerful noble in the Holy Roman Empire.

In 1623, he cleared away twenty-six houses and six gardens in Prague to begin construction of a palace, which he intended to rival the grandeur of nearby Hradčany Castle. He employed Italian architects and artisans to create gardens and decorate the interior with frescos, which featured astrological and mythological themes, including one which featured Wallenstein as the war god Mars riding a chariot across the sky. The interior furnishings alone were later estimated to be worth seventy thousand pure gold coins, and the tableware and jewels used throughout the palace were worth 134,000 – all of which had been obtained with debased, copper-infused money.

The Wallenstein Palace, along with its gardens and its fresco of Albrecht von Wallenstein as Mars, remains in the center of Prague to this day.

* * *

While the nobles increased their land holdings and the emperor waged war with armies paid for with debased money, the copper-infused coinage began to spread throughout Bohemia and into the surrounding realms. For those who held coins that were partially copper, and who knew they did not contain as much gold and silver as they were supposed to, there was a tremendous incentive to quickly exchange those devalued coins for coins with the same stamped denomination on their faces, but which were made of pure gold or silver. Instant profit would be made, however dubious. Yet the profit could only be had if the holders of pure coins didn’t suspect they were being given devalued coins in return.

The Clippers and Whippers, or Kipper und Wipper as they were known, were those perpetrators who dishonestly kept their scales in motion while weighing out coins during transactions, so as to conceal the different weight of devalued coins partially made of copper and other metals. Kipper derives from the Low German kippen, which means “to tilt,” and wippen means “to wag” back and forth, as the scales of the time would do while in motion. Perhaps appropriately, the root wippe in German also referred to a method of torture. For the unsuspecting citizenry, all of these connotations would soon be keenly felt.

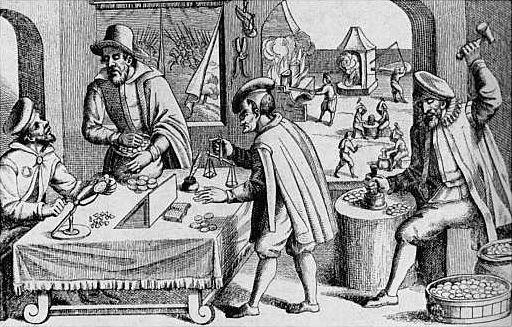

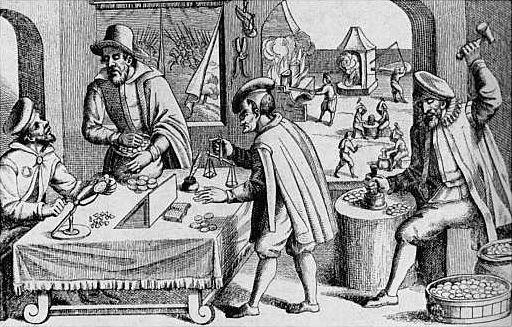

A depiction of the practice of coin devaluation and exchanging during the so-called “tipper and whipper time.” The man in the center can be seen holding a scale common for weighing coins at the time. From a woodblock print.

As the agents of Kipper und Wipper spread throughout greater Germany exchanging bad coins for good, the demand for mints that could melt down pure coins and multiply them with copper increased dramatically. According to a contemporary account, new mints began to spring up “like mushrooms after a warm rain,” even though many of them had not been granted the legal right to stamp coins. In 1620 there were seventeen mints in Brunswick, a hub of commerce and trade northwest of Prague, but three years later there were forty, including a hastily converted convent that employed as many as four hundred workers.

A low-grade silver 150-Kreuzer piece from the Prague mint in 1622

Although it was illegal to produce coins with less gold or silver than they were supposed to contain, even the officially sanctioned mints circumvented this by keeping a small supply of pure coins on hand to show the general assayers when they visited for inspections. The prospect of immediate, immense profits from minting a greater number of coins from a limited supply of gold and silver proved irresistible. And as the supply of new coins increased exponentially after 1618 along with the mushrooming number of mints, the Kipper und Wipperzeit inflation began.

A low-grade silver 60 groschen piece by Johann Georg I (1611–1656), Elector of Saxony, from the Dresden Mint in 1622

At first, it sparked a boom. With more money circulating, farmers, craftsmen and merchants began to earn more for the goods they produced and sold. Many of these prosperous citizens suddenly felt richer. Yet it paled in comparison to the already wealthy, whose vast stores of gold and silver could be melted down and turned into more money practically overnight. They spent this seemingly newfound wealth with greater abandon, and the prices for goods of all sorts began rising with the increase in demand, fueling a growing ebullient sentiment that nearly everyone was rapidly growing wealthier and more prosperous.

Industry and trade also boomed. As imports from abroad, such as wool from England, and other goods which had to be paid for with foreign coins of pure gold and silver became increasingly expensive, less expensive, locally produced goods experienced a surge in demand. Exports also surged, as goods produced locally with cheaper, debased money could be sold abroad for much higher prices, with pure gold and silver received in return. Profits from selling and trading goods soared.

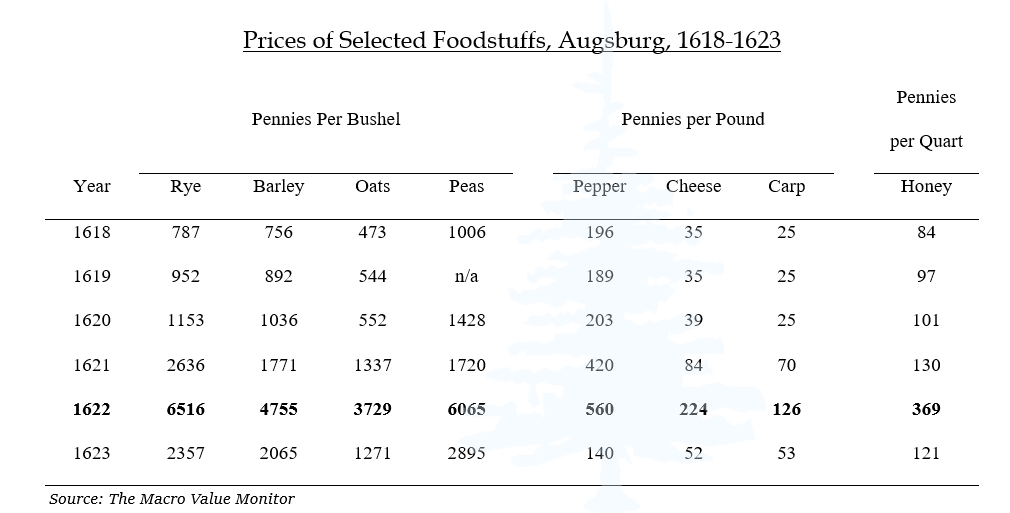

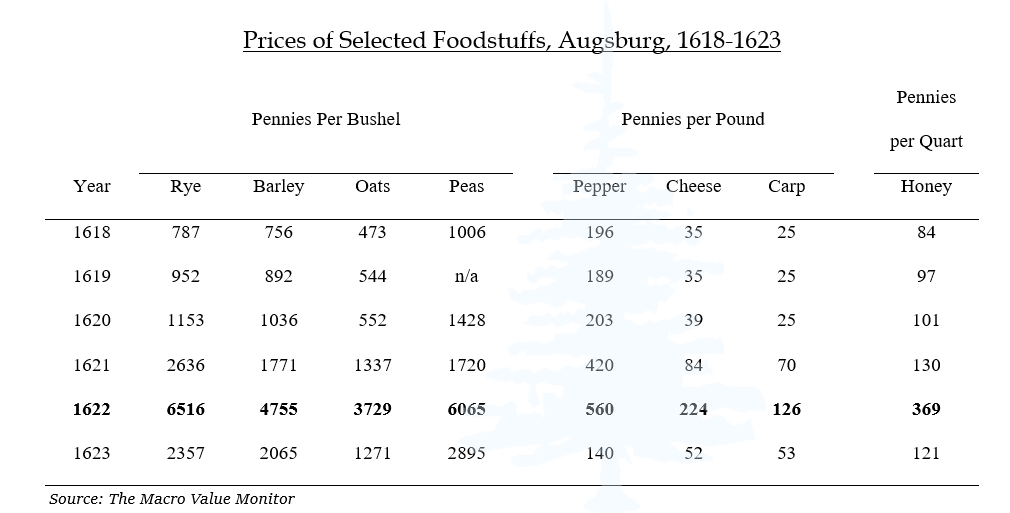

For the poor, however, and for those did not own producing land, such as most of those workers who lived in the towns and cities, life quickly became much harder. The profits made from selling goods at higher prices came at the expense of those who sold only their labor, as the wages workers earned (paid in debased coins) failed to keep up with the rising prices of food and other daily goods. Servants, laborers, teachers, miners, carters, boatmen and priests all saw their prospects dim. In Augsburg, journeyman wages relative to the rising price of rye fell precipitously as debased coinage spread: the cost of a worker’s daily bread nearly tripled relative to their wages, and the cost of other goods increased even more.

The boom proved short-lived.

Seeking ever higher profits, the mints producing the debased coinage continually increased the amounts of copper and other metal alloys in the coins they churned out, and as coins contained less and less gold and silver, skepticism of the value of money began to erode confidence. As more people came to distrust the value of the money they received for their goods and services, coins began to lose their utility as a medium of exchange, and trade began to stagnate. Instead, the debased coinage became the focus of intense speculation among people of all trades.

As soon as one receives a penny or a groschen he becomes a profiteer… profits are followed rather than Hippocrates and Galenus, while judges forget the law, hang their practices on the wall and let others read Bartholus and Baldus. The same is true of other learned folk, studying speculation more than rhetoric and philosophy; merchants, retailers and other tradespeople push their businesses with short goods, which are then marked with a mint stamp.

Increasingly skeptical farmers began to demand payment in large denomination coins that they felt confident were pure gold or silver, and when they were unable to be paid in money of certain value, they refused to bring their goods to market. Wage earners in the cities who were paid in debased coin increasingly found there was no food available to buy with their money, at any price. In the town of Ravensburg, southwest of Prague, a contemporary observer wrote in 1623 that “[t]he farmers are treating the starving population so horribly that even a stone would be moved to pity.”

As prices continued to rise and goods and services became scarce, riots began to break out. The mobs targeted those they felt were benefitting from their want and hunger. The houses of exchange dealers and mint masters in Brandenburg and Halberstadt were stormed in 1621, and mobs then pillaged wealthy manufactures. In February of the following year, a riot in Magdeburg ended with sixteen dead and two hundred wounded. In Krakow crowds clashed with the local government in 1622 and 1623.

Yet while the rioters vented their anger toward those among them who were seemingly profiting at their expense, they blamed not the nobles and princes who had established the mints in the first place, and profited the greatest by the debasement. The nobles had first access to the debased coinage, and they used the devalued to money to acquire estates, fund conquests and pay workers – all at a severe discount to the cost in pure gold and silver. Albrecht von Wallenstein used his first-in-line access to the effluence from the mints to acquire wealth almost beyond imagination.

However, when these same nobles and princes began to receive rents and debts they were owed in debased coin, they acted swiftly to end the Kipper und Wipperzeit inflation. In 1623, throughout the patchwork of realms in the Holy Roman Empire resolutions were adopted that returned coins to their previous pure standards, which had been defined by Imperial Ordinance in 1559. The mint trials, the process by which the purity of each mint’s coinage was periodically verified, but which had conveniently been allowed to lapse during the debasement, were re-instituted.

In February 1624, Emperor Ferdinand issued an official proclamation reaffirming the old imperial coin laws, which officially retuned the coin of the entire empire back to denominations made purely of gold and silver. All of the existing coinage was to be melted down, with the holders of debased coins receiving only the amount of gold and silver their coins contained. When it was all over, most of the citizenry was left holding only a small fraction of the money they thought they had, which is more than Germans would be able to say precisely three hundred years later, as they hauled wheelbarrows full of banknotes through the streets just to buy a loaf of bread.

* * *

Ten years later, Emperor Ferdinand began to suspect Wallenstein of a much larger scheme – a plot to assume the throne of the Holy Roman Empire. By then, Wallenstein’s wealth rivaled the Emperor’s, and the army he personally funded and commanded suddenly became a threat when it was learned he had been secretly negotiating with the powers the emperor was fighting against in the Thirty Years’ War.

Seeking to rid himself of this scheming rival who had grown too powerful, Ferdinand had a secret court in Vienna convict Wallenstein of conspiring against the empire, and on January 24, 1634, a secret patent was issued to the officers in Wallenstein’s army that removed him from command. A month later, on February 18, a public proclamation was issued in Prague which charged Wallenstein with high treason, and he was ordered to be brought to justice – dead or alive.

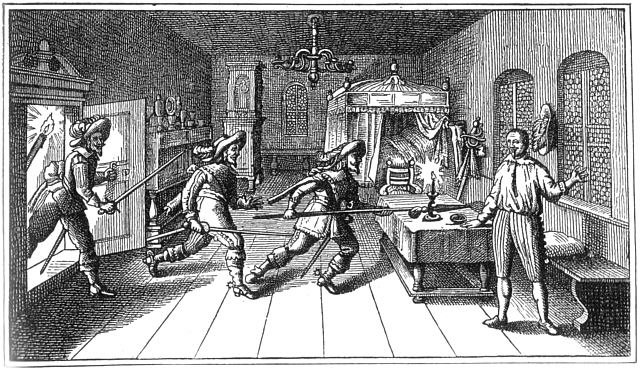

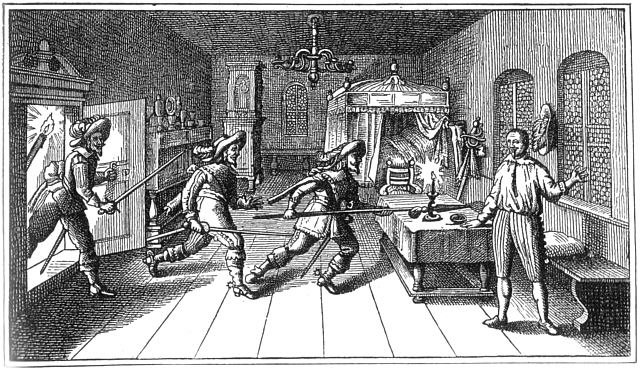

Upon learning of the charges, Wallenstein fled west with a hundred soldiers to the town of Cheb, hoping to find refuge with the Swedish army. They were welcomed into Cheb Castle upon arrival, but as the men dined at a feast on the evening of February 25, a contingent of Irish and Scottish officers loyal to the emperor led a regiment of dragoons into the castle and massacred them. Then, an Irish captain, Walter Devereux, found the house in the main square where Wallenstein was staying, and kicked in the door. Wallenstein, roused from sleep, pleaded for mercy, but Devereux quickly ran him through with the point of his spear.

Thus marked the end of the noble born into modest means in Heřmanice, and his not-so modest ambition.

The assassination of Albrecht Eusebius Wenzel von Wallenstein in Cheb, in 1634

The above is Part I of Volume II Issue I of The Macro Value Monitor, a publication focusing on Monetary History, Market Myths, Investing Legends, and Real Global Value.

Part II, The Arrival of Inflation Heralds the Dawn of a Great Partitioning, is available on Substack.

The content of this document is provided as general information and is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment or other advice. This material is not to be construed as a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any security, financial product, instrument or to participate in any particular trading strategy. Not all securities, products or services described are available in all countries, and nothing herein constitutes an offer or solicitation of any securities, products or services in any jurisdiction where their offer or sale is not qualified or exempt from registration or otherwise legally permissible.

Although the material herein is based upon information considered reliable and up-to-date, Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC does not assure that this material is accurate, current, or complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. Content in this document may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted, in whole or in part, without prior written consent from Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC — which is usually gladly given, as long as its use includes clear and proper attribution. Contact us for more information.

© Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC

Kipper und Wipperzeit

January 31, 2023

It must all go to wrack and ruin, it cannot last for long, for it is now the devil’s work, and it will spawn a noble brood:

Clippers and whippers they are called, and thought to show great intelligence. Although it’s but the devil’s trick, they think it’s a masterpiece, whereby, beneath the guise of right, they rob the poor of all they possess.

These godless folks have as their aim, in daytime and as well as night, to ruin the poor, and do not spare, whatever they’ve set in their sight…

~ Translated from an early 17th century German broadsheet

Early in the morning on Tuesday, May 23, in the year 1618, four Catholic lords entered the Bohemian Chancellory in Hradčany Castle, just west of the Vltava River in Prague. They proceeded directly to the main meeting hall, where they began preparing for the imminent arrival of the Protestant members of the recently dissolved Bohemian Assembly.

The Protestant lords were descending on Hradčany Castle that morning to learn whether the Catholic lords had a hand in persuading the new King of Bohemia, Ferdinand of Styria, to order the cessation of construction of Protestant churches on royal land. Although Habsburg emperors had been increasing Protestant rights and freedoms throughout the Holy Roman Empire, including the right to build Protestant churches on royal land, Ferdinand was a proponent of the Catholic Counter-Reformation. Upon his ascension to Bohemia’s throne in 1617, construction of Protestant churches on royal land in Bohemia had been halted. When the Protestant members of the Bohemian Assembly protested this infringement on their new rights, the new king responded by dissolving the Assembly. Incensed, the lords of Bohemia’s three main Protestant estates were demanding answers – and they arrived at the Chancellory meeting hall promptly at 9 a.m. to get them.

As the meeting commenced, Protestant Lord Paul Rziczan addressed the gathered members and described the contents of a letter they had received from the king, which had condemned the Protestant members of the Assembly, before directing his inquiry to the four Catholic lords present in the meeting hall:

His Imperial Majesty had sent to their graces the lord regents a sharp letter that was, by our request, issued to us as a copy after the original had been read aloud, and in which His Majesty declared all of our lives and honour already forfeit, thereby greatly frightening all three Protestant estates. As they also absolutely intended to proceed with the execution against us, we came to a unanimous agreement among ourselves that, regardless of any loss of life and limb, honour and property, we would stand firm, with all for one and one for all … nor would we be subservient, but rather we would loyally help and protect each other to the utmost, against all difficulties. Because, however, it is clear that such a letter came about through the advice of some of our religious enemies, we wish to know, and hereby ask the lord regents present, if all or some of them knew of the letter, recommended it, and approved of it.

Upon hearing this accusation of conspiracy against the Protestant lords, the Catholic lords requested leave to seek the counsel of their leader, who was not present in the Chancellory that morning, before giving the full Assembly their response. But the Protestant lords refused to allow them out of their sights – they demanded an immediate answer.

Two of the Catholic lords, Adam II von Sternberg and Matthew Leopold Popel Lobkowitz, were found innocent in the ensuing interrogation, after being vouched for by their fellow Protestant assemblymen. Their piety and devotion made such a conspiracy with the king seem beyond their capability. They were removed from the meeting hall, with Adam II von Sternberg vehemently declaring as he left that they had never advised anything impinging on established Protestant rights.

The remaining two Catholic lords – Count Vilem Slavata of Chlum, and Count Jaroslav Bořita of Martinice – were known Catholic hardliners and supporters of the new king. Under further questioning they eventually admitted their role in the king’s letter condemning the Protestant lords, and told the gathered Assembly they would gladly accept being arrested and imprisoned for such a worthy Catholic cause.

The Protestant lords had other ideas. One of them, Count von Thurn, turned to Slavata and Bořita and said:

“You are enemies of us and of our religion, have desired to deprive us of our [rights], have horribly plagued your Protestant subjects … and have tried to force them to adopt your religion against their wills or have had them expelled for this reason.” Then, addressing the entire Assembly, he declared: “Were we to keep these men alive, then we would lose [our rights] and our religion … for there can be no justice to be gained from or by them.”

The incited Protestant lords then rose up and proceeded to throw Slavata, Bořita and their attending scribe out of the top floor windows of the castle tower, where they plummeted seventy feet to the ground below.

Miraculously, they survived.

According to Catholic legend, they were caught in mid-air by angels, or possibly by the Virgin Mary herself, and then settled gently upon the ground. According to the Protestant pamphlets which circulated throughout Bohemia shortly afterward, they survived by landing on a soft mound of dung at the base of the tower; which may have been more of a metaphorical retort than a claim of literal fact.

Either by angels or by dung, real or otherwise, the two Catholic lords and their faithful scribe fled Prague alive, and as news of the defenestration spread, Catholic and Protestant realms throughout the Holy Roman Empire began preparing for war.

* * *

Albrecht Eusebius Wenzel von Wallenstein was born into modest means, by noble standards, but the same would not be said of his ambition. His parents, father Vilém and mother Markéta, welcomed him into the world on September 24, 1583, in Heřmanice, Bohemia, in modern-day Czech Republic. This was then the largest and easternmost province of the Holy Roman Empire. Though his parents were relatively poor, they belonged to a branch of the Waldstein family, which owned Heřmanice Castle and seven surrounding villages. And being part of the old aristocracy, they were connected with some of the wealthiest families in Bohemia.

Young Wallenstein was raised by his uncle Heinrish Slawata von Chlum after both of his parents had passed away by 1595. His uncle sent him first to the school of the Bohemian Brothers in Koschumberg, and then in 1597 to the Protestant school at Goldberg, in Silesia. In 1599 he enrolled at the Protestant Academy in Altof, near Nuremberg, Franconia, but the following year was dismissed on account of brawling and épée fighting, which also landed him in prison.

Upon his release from prison, Wallenstein served as a page at the court of Margrave Karl of Burgau, in Innsbruck, where he also survived a long fall from a high window – an event which seems to mark a number of pivotal moments in European history. Though it is unknown whether he fell or was thrown out the window, it is known that he converted to Catholicism shortly afterwards; a contemporary of Wallenstein’s, Franz Christoph von Khevenhüller, credited the Virgin Mary with saving his life during his fall. Yet however divinely inspired it was, his conversion also furthered to his ambition to climb the social ladder and serve in higher offices in the Counter-Reformation-minded Habsburg courts.

In the years that followed his brief time in Innsbruck, and his fall from the window, Wallenstein traveled throughout the Holy Roman Empire, Holland, France and Italy, where he stayed at the universities of Bologna and Padua, studying astrology and military tactics. Italy made a strong impression on him, an impression that would be infused into his estates in later years, and he became fluent in Latin and Italian, along with his native German and Czech. He also learned French and Spanish. Upon returning to Bohemia in 1604, he served in the Imperial Army in Hungary for two years, fighting the Turks and the Protestant Hungarians – where he distinguished himself.

Yet it was 1609 that brought the most important event that shaped young Wallenstein’s life, and it happened not on a battlefield, nor at a far-off university. That year he married Lucretia Nekesch von Landek, the very rich Moravian widow of Arkleb of Víckov, who owned the towns of Vsetín, Lukov, Rymice and Všetuly/Holešoy, and surrounding villages. Although the marriage was destined to be brief, as Lucretia died shortly thereafter in 1614, it provided Wallenstein with a vast estate upon her passing. This inheritance, along with the estate he inherited from his uncle Heinrish, had made Wallenstein, at the age of just thirty-one, one of the wealthiest noblemen in Bohemia.

Albrecht Eusebius Wenzel von Wallenstein Portrait by Anthony Van Dyck, 1629

Not wasting any time, the ambitious Wallenstein immediately proceeded to use his vast wealth to increase and solidify his position in the Habsburg court. In 1617, the new King of Bohemia, Ferdinand of Styria, who would the following year end construction of Protestant churches on royal land in Bohemia and then dissolve the Bohemian Assembly after the Protestant lords protested, waged war on Venice. Wallenstein immediately sent troops at his own expense to aid the king, and led them himself. He and his two hundred mounted troops relieved the fortress of Gradisca in northern Italy from a Venetian siege, where he again distinguished himself bravely in battle.

When the Catholic nobels and their scribe were thrown from the tower windows of Hradčany Castle in Prague the following spring, it marked the beginning of one of the most destructive conflicts in European history – the Thirty Years’ War. After the Catholic lords fled Prague, Count von Thurn, the Protestant lord who had led the questioning of the four Catholic lords in the meeting of the dissolved Assembly and incited the defenestration, formed a rival government and raised an army to challenge Ferdinand for the throne of Bohemia. The Protestant estates of Bohemia successfully deposed Ferdinand in August. However, two days after Ferdinand was deposed as King of Bohemia, he was elected Holy Roman Emperor, and as emperor he eventually reclaimed Bohemia and Prague for the Catholic Habsburgs after the Battle of White Mountain on November 8, 1620.

Although the Battle of White Mountain was only the first major battle of the long Thirty Years’ War, the Habsburgs entered the conflict financially exhausted. They had no standing army in 1618, and after King Ferdinand was deposed in Bohemia, they had pleaded for financial aid from abroad and had, in desperation, contracted mercenaries to face Count von Thurn’s armies. But Emperor Ferdinand could not afford to pay the mercenaries’ salaries. He quickly needed a large sum of gold and silver, but there were no capital markets from which he could borrow, and levying new taxes was difficult and would take time – time the emperor did not have. Desperate times called for desperate measures, and to finance the recapture of Bohemia, the emperor had turned to Wallenstein.

Emperor Ferdinand agreed to lease control of all the mints of Bohemia, neighboring Moravia and Lower Austria to Wallenstein and a consortium of wealthy nobles in exchange for a supplying him with enough money to pay his armies. The deal gave the emperor large guaranteed payments, which he desperately needed, in exchange for the opportunity for the consortium to profit from turning gold and silver into official currency. The consortium was granted the exclusive right to strike large and small coin denominations in those regions, with the purity of those gold and silver coins – the amount of gold and silver each coin denomination contained – having long been established by an Imperial Ordinance in place since 1559.

Wallenstein and the consortium, however, had seen a golden opportunity. A tremendous profit could be made if coins were minted with less gold and silver than specified, which would allow more coins to be made from the gold and silver the consortium had on hand. To this end, copper began to be mixed in with gold and silver to inflate the amount of raw alloy the mints had to strike official coins. The consortium delivered the copper-infused money to the emperor so he could pay his armies, and then sent agents to neighboring territories to exchange the copper-infused coins for coins that were pure gold and silver from unsuspecting merchants and peasants. These pure coins were brought back, melted down, and then the number multiplied by striking new copper-infused coins.

Wallenstein and the consortium reaped a tremendous profit from the mint operations, and it allowed him to increase his already vast wealth by leaps and bounds. As the emperor’s armies regained territory from the Protestants, Wallenstein claimed close to sixty estates in Bohemia, either by confiscating them directly, or by purchasing them with devalued, copper-infused money. The other nobles, many of whom remained anonymous, profited as well, but did not parlay their mint profits as shrewdly as Wallenstein. By the time of the consortium’s final mint contract in 1622, at the age of thirty-nine Wallenstein was funding his own armies and had become the most powerful noble in the Holy Roman Empire.

In 1623, he cleared away twenty-six houses and six gardens in Prague to begin construction of a palace, which he intended to rival the grandeur of nearby Hradčany Castle. He employed Italian architects and artisans to create gardens and decorate the interior with frescos, which featured astrological and mythological themes, including one which featured Wallenstein as the war god Mars riding a chariot across the sky. The interior furnishings alone were later estimated to be worth seventy thousand pure gold coins, and the tableware and jewels used throughout the palace were worth 134,000 – all of which had been obtained with debased, copper-infused money.

The Wallenstein Palace, along with its gardens and its fresco of Albrecht von Wallenstein as Mars, remains in the center of Prague to this day.

* * *

While the nobles increased their land holdings and the emperor waged war with armies paid for with debased money, the copper-infused coinage began to spread throughout Bohemia and into the surrounding realms. For those who held coins that were partially copper, and who knew they did not contain as much gold and silver as they were supposed to, there was a tremendous incentive to quickly exchange those devalued coins for coins with the same stamped denomination on their faces, but which were made of pure gold or silver. Instant profit would be made, however dubious. Yet the profit could only be had if the holders of pure coins didn’t suspect they were being given devalued coins in return.

The Clippers and Whippers, or Kipper und Wipper as they were known, were those perpetrators who dishonestly kept their scales in motion while weighing out coins during transactions, so as to conceal the different weight of devalued coins partially made of copper and other metals. Kipper derives from the Low German kippen, which means “to tilt,” and wippen means “to wag” back and forth, as the scales of the time would do while in motion. Perhaps appropriately, the root wippe in German also referred to a method of torture. For the unsuspecting citizenry, all of these connotations would soon be keenly felt.

A depiction of the practice of coin devaluation and exchanging during the so-called “tipper and whipper time.” The man in the center can be seen holding a scale common for weighing coins at the time. From a woodblock print.

As the agents of Kipper und Wipper spread throughout greater Germany exchanging bad coins for good, the demand for mints that could melt down pure coins and multiply them with copper increased dramatically. According to a contemporary account, new mints began to spring up “like mushrooms after a warm rain,” even though many of them had not been granted the legal right to stamp coins. In 1620 there were seventeen mints in Brunswick, a hub of commerce and trade northwest of Prague, but three years later there were forty, including a hastily converted convent that employed as many as four hundred workers.

A low-grade silver 150-Kreuzer piece from the Prague mint in 1622

Although it was illegal to produce coins with less gold or silver than they were supposed to contain, even the officially sanctioned mints circumvented this by keeping a small supply of pure coins on hand to show the general assayers when they visited for inspections. The prospect of immediate, immense profits from minting a greater number of coins from a limited supply of gold and silver proved irresistible. And as the supply of new coins increased exponentially after 1618 along with the mushrooming number of mints, the Kipper und Wipperzeit inflation began.

A low-grade silver 60 groschen piece by Johann Georg I (1611–1656), Elector of Saxony, from the Dresden Mint in 1622

At first, it sparked a boom. With more money circulating, farmers, craftsmen and merchants began to earn more for the goods they produced and sold. Many of these prosperous citizens suddenly felt richer. Yet it paled in comparison to the already wealthy, whose vast stores of gold and silver could be melted down and turned into more money practically overnight. They spent this seemingly newfound wealth with greater abandon, and the prices for goods of all sorts began rising with the increase in demand, fueling a growing ebullient sentiment that nearly everyone was rapidly growing wealthier and more prosperous.

Industry and trade also boomed. As imports from abroad, such as wool from England, and other goods which had to be paid for with foreign coins of pure gold and silver became increasingly expensive, less expensive, locally produced goods experienced a surge in demand. Exports also surged, as goods produced locally with cheaper, debased money could be sold abroad for much higher prices, with pure gold and silver received in return. Profits from selling and trading goods soared.

For the poor, however, and for those did not own producing land, such as most of those workers who lived in the towns and cities, life quickly became much harder. The profits made from selling goods at higher prices came at the expense of those who sold only their labor, as the wages workers earned (paid in debased coins) failed to keep up with the rising prices of food and other daily goods. Servants, laborers, teachers, miners, carters, boatmen and priests all saw their prospects dim. In Augsburg, journeyman wages relative to the rising price of rye fell precipitously as debased coinage spread: the cost of a worker’s daily bread nearly tripled relative to their wages, and the cost of other goods increased even more.

The boom proved short-lived.

Seeking ever higher profits, the mints producing the debased coinage continually increased the amounts of copper and other metal alloys in the coins they churned out, and as coins contained less and less gold and silver, skepticism of the value of money began to erode confidence. As more people came to distrust the value of the money they received for their goods and services, coins began to lose their utility as a medium of exchange, and trade began to stagnate. Instead, the debased coinage became the focus of intense speculation among people of all trades.

As soon as one receives a penny or a groschen he becomes a profiteer… profits are followed rather than Hippocrates and Galenus, while judges forget the law, hang their practices on the wall and let others read Bartholus and Baldus. The same is true of other learned folk, studying speculation more than rhetoric and philosophy; merchants, retailers and other tradespeople push their businesses with short goods, which are then marked with a mint stamp.

Increasingly skeptical farmers began to demand payment in large denomination coins that they felt confident were pure gold or silver, and when they were unable to be paid in money of certain value, they refused to bring their goods to market. Wage earners in the cities who were paid in debased coin increasingly found there was no food available to buy with their money, at any price. In the town of Ravensburg, southwest of Prague, a contemporary observer wrote in 1623 that “[t]he farmers are treating the starving population so horribly that even a stone would be moved to pity.”

As prices continued to rise and goods and services became scarce, riots began to break out. The mobs targeted those they felt were benefitting from their want and hunger. The houses of exchange dealers and mint masters in Brandenburg and Halberstadt were stormed in 1621, and mobs then pillaged wealthy manufactures. In February of the following year, a riot in Magdeburg ended with sixteen dead and two hundred wounded. In Krakow crowds clashed with the local government in 1622 and 1623.

Yet while the rioters vented their anger toward those among them who were seemingly profiting at their expense, they blamed not the nobles and princes who had established the mints in the first place, and profited the greatest by the debasement. The nobles had first access to the debased coinage, and they used the devalued to money to acquire estates, fund conquests and pay workers – all at a severe discount to the cost in pure gold and silver. Albrecht von Wallenstein used his first-in-line access to the effluence from the mints to acquire wealth almost beyond imagination.

However, when these same nobles and princes began to receive rents and debts they were owed in debased coin, they acted swiftly to end the Kipper und Wipperzeit inflation. In 1623, throughout the patchwork of realms in the Holy Roman Empire resolutions were adopted that returned coins to their previous pure standards, which had been defined by Imperial Ordinance in 1559. The mint trials, the process by which the purity of each mint’s coinage was periodically verified, but which had conveniently been allowed to lapse during the debasement, were re-instituted.

In February 1624, Emperor Ferdinand issued an official proclamation reaffirming the old imperial coin laws, which officially retuned the coin of the entire empire back to denominations made purely of gold and silver. All of the existing coinage was to be melted down, with the holders of debased coins receiving only the amount of gold and silver their coins contained. When it was all over, most of the citizenry was left holding only a small fraction of the money they thought they had, which is more than Germans would be able to say precisely three hundred years later, as they hauled wheelbarrows full of banknotes through the streets just to buy a loaf of bread.

* * *

Ten years later, Emperor Ferdinand began to suspect Wallenstein of a much larger scheme – a plot to assume the throne of the Holy Roman Empire. By then, Wallenstein’s wealth rivaled the Emperor’s, and the army he personally funded and commanded suddenly became a threat when it was learned he had been secretly negotiating with the powers the emperor was fighting against in the Thirty Years’ War.

Seeking to rid himself of this scheming rival who had grown too powerful, Ferdinand had a secret court in Vienna convict Wallenstein of conspiring against the empire, and on January 24, 1634, a secret patent was issued to the officers in Wallenstein’s army that removed him from command. A month later, on February 18, a public proclamation was issued in Prague which charged Wallenstein with high treason, and he was ordered to be brought to justice – dead or alive.

Upon learning of the charges, Wallenstein fled west with a hundred soldiers to the town of Cheb, hoping to find refuge with the Swedish army. They were welcomed into Cheb Castle upon arrival, but as the men dined at a feast on the evening of February 25, a contingent of Irish and Scottish officers loyal to the emperor led a regiment of dragoons into the castle and massacred them. Then, an Irish captain, Walter Devereux, found the house in the main square where Wallenstein was staying, and kicked in the door. Wallenstein, roused from sleep, pleaded for mercy, but Devereux quickly ran him through with the point of his spear.

Thus marked the end of the noble born into modest means in Heřmanice, and his not-so modest ambition.

The assassination of Albrecht Eusebius Wenzel von Wallenstein in Cheb, in 1634

The above is Part I of Volume II Issue I of The Macro Value Monitor, a publication focusing on Monetary History, Market Myths, Investing Legends, and Real Global Value.

Part II, The Arrival of Inflation Heralds the Dawn of a Great Partitioning, is available on Substack.

The content of this document is provided as general information and is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment or other advice. This material is not to be construed as a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any security, financial product, instrument or to participate in any particular trading strategy. Not all securities, products or services described are available in all countries, and nothing herein constitutes an offer or solicitation of any securities, products or services in any jurisdiction where their offer or sale is not qualified or exempt from registration or otherwise legally permissible.

Although the material herein is based upon information considered reliable and up-to-date, Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC does not assure that this material is accurate, current, or complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. Content in this document may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted, in whole or in part, without prior written consent from Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC — which is usually gladly given, as long as its use includes clear and proper attribution. Contact us for more information.

© Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC

Investment Management

Before investing, we will discuss your goals and risk tolerances with you to see if a separately managed account at Sitka Pacific would be a good fit. To contact us for a free consultation, visit Getting Started.

Macro Value Monitor

To read a selection of recent client letters and be alerted when new letters are posted to our public site, visit Recent Client Letters.