Checkers vs Chess Amid an Inflationary Great Mistake

June 30, 2023

Roughly a year into their campaign against high inflation, policy makers are some way from being able to declare victory. In the U.S. and Europe, underlying inflation is still around 5% or higher even as last year’s heady increases in energy and food prices fade from view. On both sides of the Atlantic, wage growth has stabilized at high levels and shows few signs of steady declines…

All that puts major central banks in a tricky spot. They need to decide if inflation has stalled way above their 2% target, which could require much higher interest rates to fix, or if inflation’s decline is only delayed. Get the call wrong, and they could push the rich world into a deep recession or force it to endure years of high inflation.

“It’s not an enviable situation that central banks are in,” said Stefan Gerlach, a former deputy governor of Ireland’s central bank. “You could make a major mistake either way.”

~ The Wall Street Journal, June 19, 2023

Chess is like looking across an ocean. Checkers is like looking down a well.

~ Dr. Marion F. Tinsley

Inflation Strategy Amid Monetary Stimulants Gone Awry

One year ago, we visited the pages of a diary from 1931, a diary which contained the thoughts of a young lawyer in Youngstown, Ohio, who was living through the early days of the Great Depression. Benjamin Roth began to write down his thoughts and record the events around him when he realized he was living through a period of economic turmoil that was different from anything else he had experienced up to that time.

After World War I, Roth had witnessed the post-war boom when he arrived back home from Europe. At the time, soaring retail sales and real estate prices accompanied the return of soldiers and the end of the wartime economy, as exuberant consumers, flush with cash, shed the austere mentality of the war years and spent lavishly. As we chronicled in these pages last April, this postwar boom ended in a brief depression when the Federal Reserve decided to tackle inflation by shrinking its balance sheet in 1921, a downturn which bankrupted future president Harry Truman’s haberdashery, Truman & Jacobson.

In the years that followed the early 1920s depression, however, the economy had boomed again. Roth began his diary by noting how extraordinary the 1920s economy was. With Europe in ruins, America became the main supplier for raw materials and consumer goods to Western Europe, as well as American consumers. Mass-produced manufactured goods such as radios and automobiles were newly affordable to the masses, and production and employment soared. The stock market boomed as well, and for the first time, the broader public became enchanted with Wall Street. Companies began issuing “common shares” for the first time in the early 1920s. Although they did not have a guaranteed dividend like their preferred relatives, common shares were issued in smaller denominations, and that opened the floodgates to millions of investors and speculators.

Yet, as Roth reflected in 1931, the economy had also began to show cracks as early as the mid-1920s. As Wall Street boomed, it financed the first expansion of large retail chain stores into small town America, and this bankrupted thousands of small businesses in Ohio alone.

As an attorney who processed many of the bankruptcy filings, Roth witnessed this erosion of locally owned business firsthand. As a greater share of retail profits began flowing to Chicago and New York, instead of remaining in the local economy, commercial real estate in Youngstown began to falter. This was soon accompanied by a decline in farmland values, as a recovery in European farm production reduced exports and weighed down crop prices. In Youngstown, a decline in steel prices in the latter half of the 1920s hit the increasingly strained local economy particularly hard.

By 1931, it had been two years since the speculative peak of the stock market in 1929, but the steady erosion of Youngstown’s local economy dated back years before the peak in New York – and it had begun to cripple local banks. The first bank closure was announced on August 5th, 1931, when Home Savings & Loan closed its doors. For the stunned citizens of Youngstown, this marked the moment when the downturn with roots in the mid-1920s began rising above the surface in ways that put their supposedly-safe cash savings at risk.

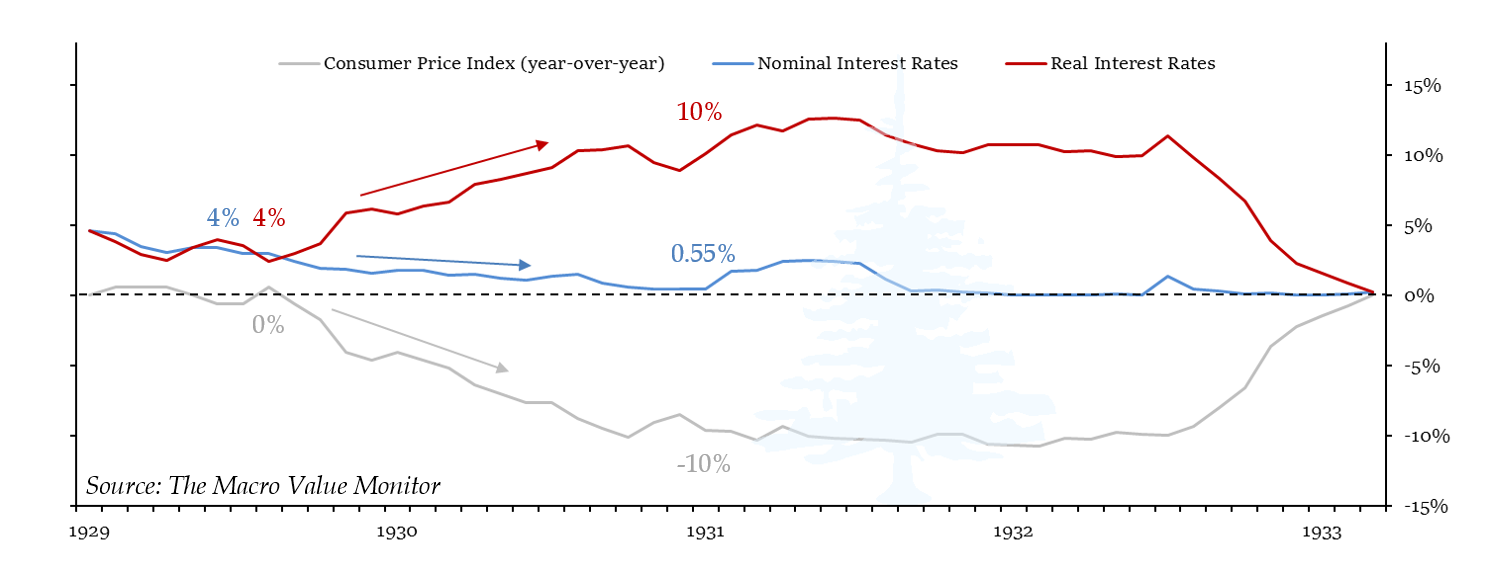

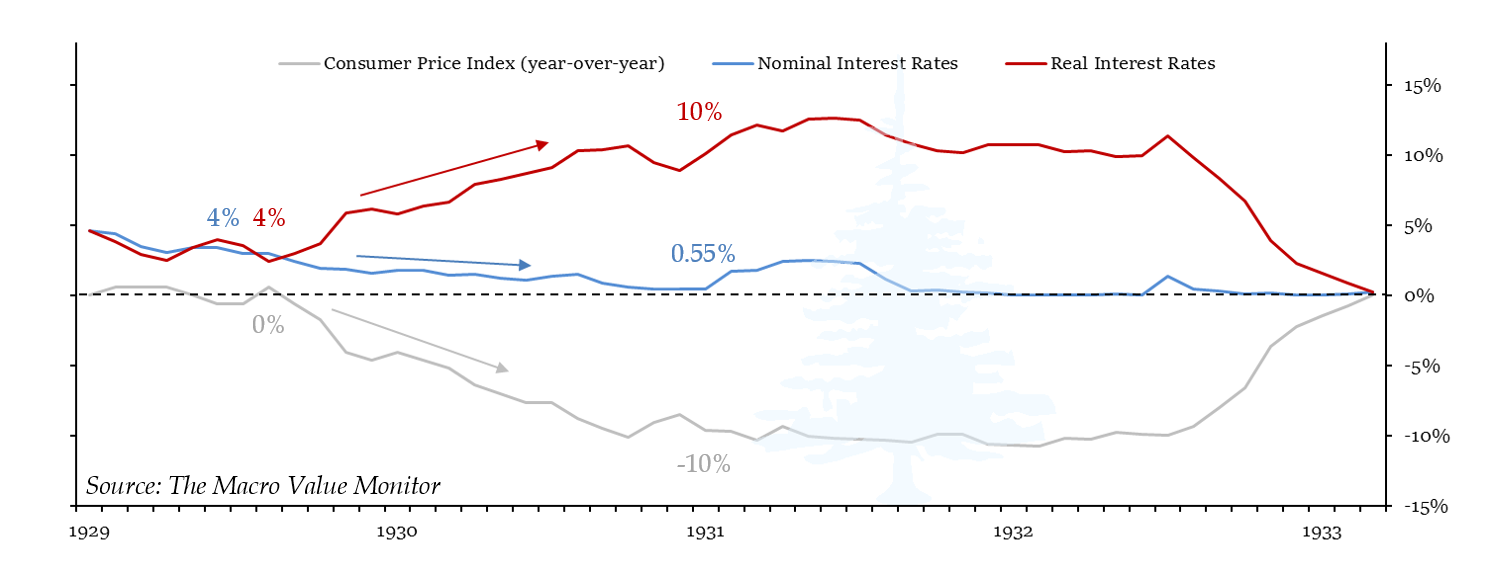

What Benjamin Roth did not know at the time, and could not have known, was that in the summer of 1931 the Federal Reserve was already in the middle of its First Great Mistake. By the time Home Savings & Loan in Youngstown failed, real, inflation-adjusted interest rates had soared, but few understood the destructive impact surging real interest rates were imparting. On the surface, it seemed as if rates were lower. Interest rates had fluctuated between 4% and 5% throughout 1929, and after the stock market crashed, they steadily declined. By the time Benjamin Roth began his diary in June 1931, interest rates had fallen to just 0.55%. These were the lowest interest rates in memory.

With interest rates near zero, many Federal Reserve governors assumed monetary policy was “loose,” but unfortunately, that was not the case. When adjusted for inflation, interest rates fluctuated between 3% and 5% throughout most of 1929, but after the stock market crashed in October 1929, prices throughout the economy began to fall: in the year after the crash, the consumer price index had declined 4%. Although nominal interest rates had declined from 4% to 1.75% during that time, real interest rates, adjusted for the 4% decline in prices, had risen to 5.75% in 1930. By 1931, the decline of prices throughout the economy accelerated to a 10% annual rate, and this translated the 0.55% nominal interest rate to a 10.55% real, deflation-adjusted interest rate.

Instead of monetary policy being “loose,” by 1931 real interest rates had risen to the highest levels in more than a decade. This surge ignited an asset liquidation and credit contraction that marked the end of the cyclical downturn from the peak in 1929, and the beginning of the Great Depression.

The Great Mistake made by the Federal Reserve in the 1930s was its failure to understand the importance of real interest rates, while also not appreciating the long-term risks that come with a large-scale, economy-wide credit contraction.

At the time, the consensus among Federal Reserve governors was that monetary policy was loose enough, with interest rates near zero. Other governors thought the economy needed a proper downturn in order to purge the excesses of the boom years, and when the downturn continued despite low interest rates, it reinforced this tough love view. As Fed governor Charles Hamlin put it in November 1929, just after the crash in the stock market the month before: “These events are deplorable, but they were of course inevitable and could not have been avoided.” Attitudes such as these led to a complacent intake of the mounting troubles in banks throughout the country after 1929, and they resulted in a hands-off approach as the economic contraction accelerated dramatically in 1931.

Yet this hands-off approach ultimately led to severe consequences for the Federal Reserve: it resulted in partial takeovers of monetary policy by the U.S. Treasury department in 1933 and 1937, and ultimately to a full takeover in 1942. The loss of independence as a result of the complacency in the early years of the Great Depression left deep scars in the halls of the Eccles building, and as a result, the Fed has aggressively intervened at every sign of incipient deflation since then.

Nine decades later, those powerful institutional memories forged by the First Great Mistake were on full display as the Federal Reserve responded to the impact of the Covid pandemic.

Two years ago, on June 16, 2021, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell took questions from reporters at his regular press conference following the meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee. At the time, the Fed had decided to keep the Fed Funds rate at zero, and had also decided to keep expanding its balance sheet by $120 billion a month. Unlike the Federal Reserve of 1931, the Federal Reserve of 2021 was convinced it could not do enough to hasten the return of a full employment economy in the wake of the pandemic, and after a decade-long recovery after the financial crisis.

When Chair Powell was asked by Rachel Seigel of The Washington Post about the Fed’s outlook for the jobs market two years hence, in 2023, given the Fed’s then-current policies, he had this to say:

So I would say, if you look at the labor market and you look at the demand for workers and the level of job creation and think ahead, I think it’s clear, and I am confident, that we are on a path to a very strong labor market—a labor market that, that shows low unemployment, high participation, rising wages for people across the spectrum. I mean, I think that’s shown in our projections, it’s shown in outside projections. And if you look through the current time frame and think one and two years out, we’re going to be looking at a very, very strong labor market…

The next reporter, Paul Kiernan of The Wall Street Journal, asked Powell how he felt about the recent rise of inflation. He pointed out that the annualized inflation rate over the prior three months had risen to 8.4%, the highest in four decades, and he asked Powell “how much longer we can sustain those, those kinds of rates before you get nervous?” Powell offered this response:

So inflation has come in above expectations over the last few months. But if you look behind the headline numbers, you’ll see that the incoming data are, are consistent with the view that prices—that prices that are driving that higher inflation are from categories that are being directly affected by the recovery from the pandemic and the reopening of the economy…

When will we be seeing [those trends reverse]? We’re not sure. That narrative seems, still seems quite likely to prove correct, although, you know, as I pointed out at the last press conference, the timing of that is, is pretty uncertain, and so are the, the effects in the near term. But over time, it seems likely that these very specific things that are driving up inflation will be—will be temporary…

So I can’t give you an exact number or an exact time, but I would say that we do expect inflation to move down. If you look at the—if you look at the forecast for 2021 and—sorry, 2022 and 2023 among my colleagues on the, on the Federal Open Market Committee, you will see that people do expect inflation to move down meaningfully toward our goal [of 2%]. And I think the full range of inflation projections for 2023 falls between 2 and 2.3 percent, which is consistent with our—with our goals.

The final exchange in the press conference came from Bloomberg’s Michael McKee. In his question, he attempted to ask Chair Powell how he was reconciling the apparent inconsistency between the discounting of the actual inflation data that was coming in, assuming it would simply resolve itself in time, while also stating the Fed would rely less on forecasts (and assumptions) and be more data-dependent in its decision making. These were the new goals the Fed outlined in its Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy the prior year.

MICHAEL MCKEE. Mr. Chairman, of course you’ll be shocked to learn that you have some critics on Wall Street. And I would like to paraphrase a couple of their criticisms and get your reaction to them. One is that the new policy framework is that you react to actual data and do not react to forecasts, yet the actual inflation data is coming in hot and you’re relying on the forecast that it will cool down in order to make policy. I wanted to get your view on how you square that. Another is that you have a long runway, you’ve said, for tapering with announcements. But if the data keep coming in faster than expected, are you trapped by fear of a taper tantrum from advancing the time period in which you announce a taper? And, finally, you’ve said the Fed knows how to combat inflation, but raising rates also slows the economy. And there’s a concern that you might be sacrificing the economy if you wait too long and have to raise rates too quickly.

CHAIR POWELL. So that’s a—that’s a few questions there. So let me say, first, I think people misinterpret the framework. I think the—there’s nothing wrong with the framework, and there’s nothing in the framework that would in any way, you know, interfere with our ability to pursue our, our goals. That’s for starters…

You know, your specific question, I guess, was, will we be behind the curve? And, you know, that’s, that’s not the situation we’re facing at all. The situation that we, we addressed in our—in our Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy was a situation in which employment was at very high levels, but inflation was low. And what we said was, we wouldn’t raise interest rates just because unemployment was low and employment was high if there was no evidence of inflation or other troubling imbalances. So that’s what we said.

That is not at all the current situation. In the current situation, we have many millions of people who are unemployed, and we have inflation running well above our target. The question we face with this inflation has nothing to do with our framework. It’s a very different, very difficult version of a standard investment—sorry, a central banking question. And that is, how do you separate in inflation—how do you separate things that, that follow from broad upward price pressures from things that really are a function of, of sort of idiosyncratic factors…

MICHAEL MCKEE. If you raise rates to control inflation, you also slow the economy. And the history of the Fed is that sometimes you go too far.

CHAIR POWELL. That’s right. And we—look, we have to balance the two—the two goals: maximum employment and price stability. Often they are—they do pull in the same direction, of course. But when we—when we raise interest rates to control inflation, there’s no question that has an effect on activity. And that’s the channel—one of the channels through which we get to inflation. We don’t think that we’re in a situation like that right now. We think that the economy is recovering from a deep hole—an unusual hole, actually, because it’s to do with, with shutting down the economy. It turns out it’s a heck of a lot easier to create demand than it is to, you know, to bring supply back up to snuff. That’s happening all over the world. There’s no reason to think that that process will last indefinitely. But we’re going, you know, we’re going to watch carefully to make sure that, that evolving inflation and our understanding of what’s happening is, is, is right. And in the meantime, we’ll conduct policy appropriately.

In these passages from Powell’s press conference two years ago, the complacency in the face of rising inflation bears an eerie resemblance to the complacency the Federal Reserve showed toward rising unemployment and bank failures after 1929.

In 1930 and 1931, the Federal Reserve operated on the assumption that the excesses of the late 1920s boom needed to be corrected, and once they were corrected, growth would resume just as it had prior to 1929, without any additional support from monetary policy. Soaring real interest rates, falling commodity prices, and the impact declining real estate values was having on bank balance sheets and broad measures of money supply, were either rationalized as necessary to correct the excesses of the late 1920s, or ignored. The depression that followed was the deepest downturn of the 20th century.

Ninety years later, in 2021, similar assumptions were made about inflation returning to its prior trajectory, without the need for any additional restraint from monetary policy, when, in fact, just as in 1931, the old regime was becoming history amid the complacency.

Monetary policy infamously operates with long and variable lags, and successively navigating the impact monetary stimulus or withdrawal has on prices throughout the economy and financial markets requires a strategic mindset that is thinking and planning many moves ahead.

Checkers and chess are both played on boards with sixty-four squares, but there the similarity ends. In the game of checkers, each piece is interchangeable, and able to move in the same way – forward. In checkers, players generally attempt to take as many of their opponent’s pieces as possible, as quickly as they can, while losing fewer of their own, using moves which are fairly linear: moving one square at a time, one jump takes one piece, two successive jumps take two pieces, etc. When a piece is “kinged,” its range of motion increases, but it continues to move in the same linear way. It is a game that largely rewards black and white, reactionary problem solving.

Chess, on the other hand, is a game which is played with different goals, and is won with a much more complex, strategic approach. With six different kinds of pieces, all of which move in different ways, and the capture of only one of which ends the game, chess is more about controlling the board than capturing or losing pieces. An almost infinite number of progressions can achieve this. As long as one’s king remains protected, other pieces can be sacrificed to establish that control, and winning is less about numerical advantage than strategic dominance. The player who dominates the board, and corners their opponent’s king in the fewest moves while protecting their own, wins the game.

In chess, if you are merely reacting to the moves your opponent makes as they make them, you are already falling into their trap and on your way to losing the game. In the financial markets, the same can be said of investors who are reacting to current data, especially current inflation data.

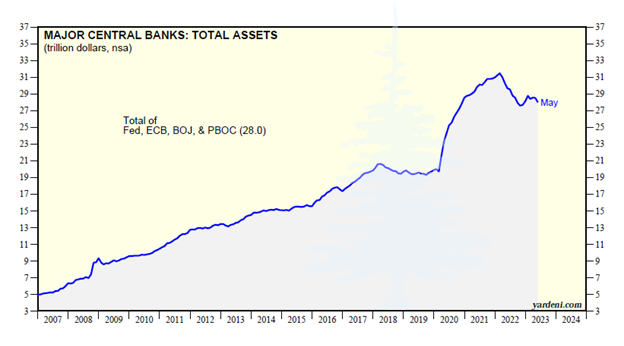

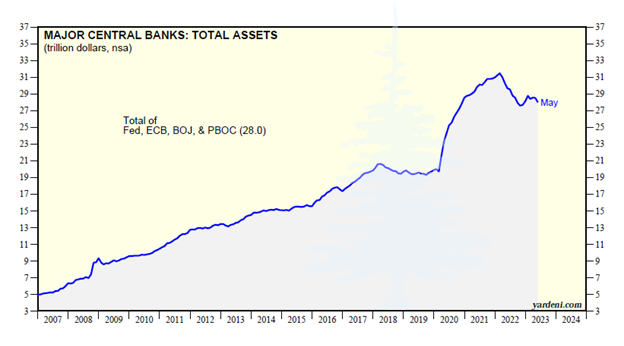

Major central banks around the world have been scrambling to address rising inflation rates since last year, but the combined balance sheet of the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, the Bank of Japan, and the People’s Bank of China highlights what they are struggling against – themselves. With a combined balance sheet 5.6 times the size it was in 2007, the global supply of money on which all credit in the largest economies is based many times larger than what it was before the financial crisis. And as we have seen in the bond market and banking turmoil in the U.K., Europe, and here in the U.S. over the past year, shrinking that base money supply is no painless task.

Price inflation is the end result of a long and variable chain of circumstances, and the root of that progression is the base money supply. Those who listened to Jerome Powell’s press conference in June 2021 with a checkers mentality, thinking linearly, and reacting to what was in the rear-view mirror, found themselves badly burned in 2022, when inflation proved far more widespread and resilient than the Fed expected. Those who listened to that same press conference with a chess mentality could visualize what the market risks were in that moment, and what the consequences could be if some of those risks surfaced. The difference in thinking in black-and-white terms, versus thinking in a more strategic manner, proved to be the difference between being trapped by the market reset in 2022, and taking advantage of it.

This past month, the Federal Reserve decided to pause its rate-hiking campaign for the first time since it belatedly began to address rising inflation a year ago. It left the Fed Funds rate target range at 5-5.25% and issued a statement that said holding interest rates at this level will allow the Fed “to assess additional information and its implications for monetary policy.”

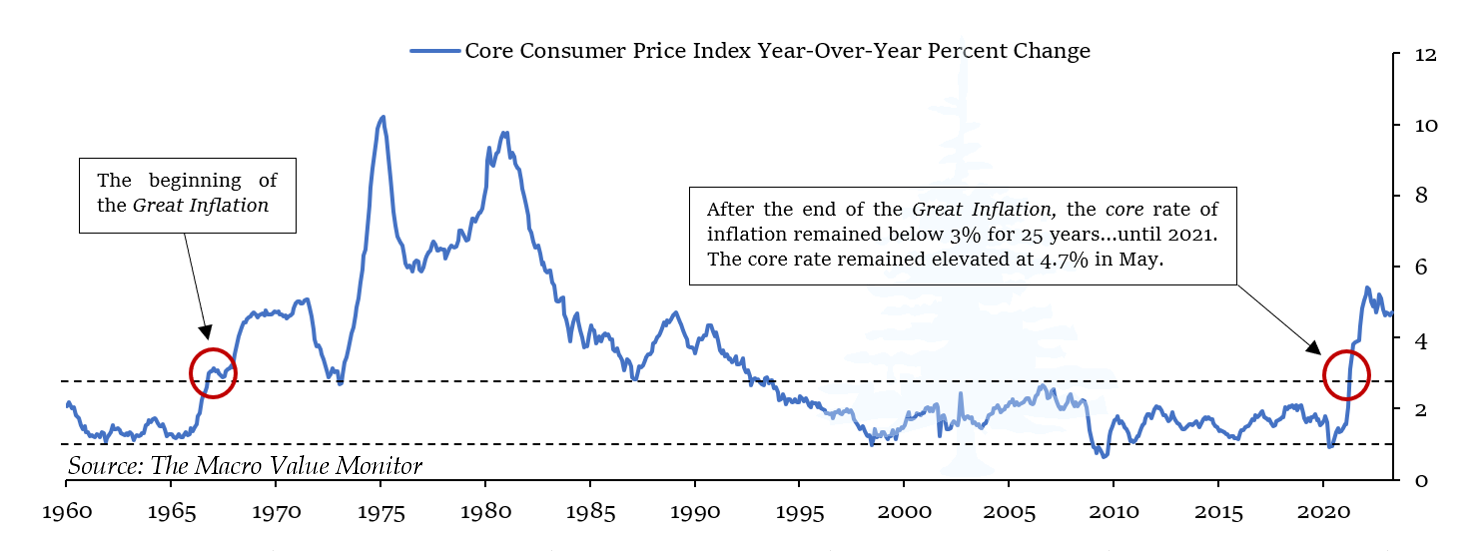

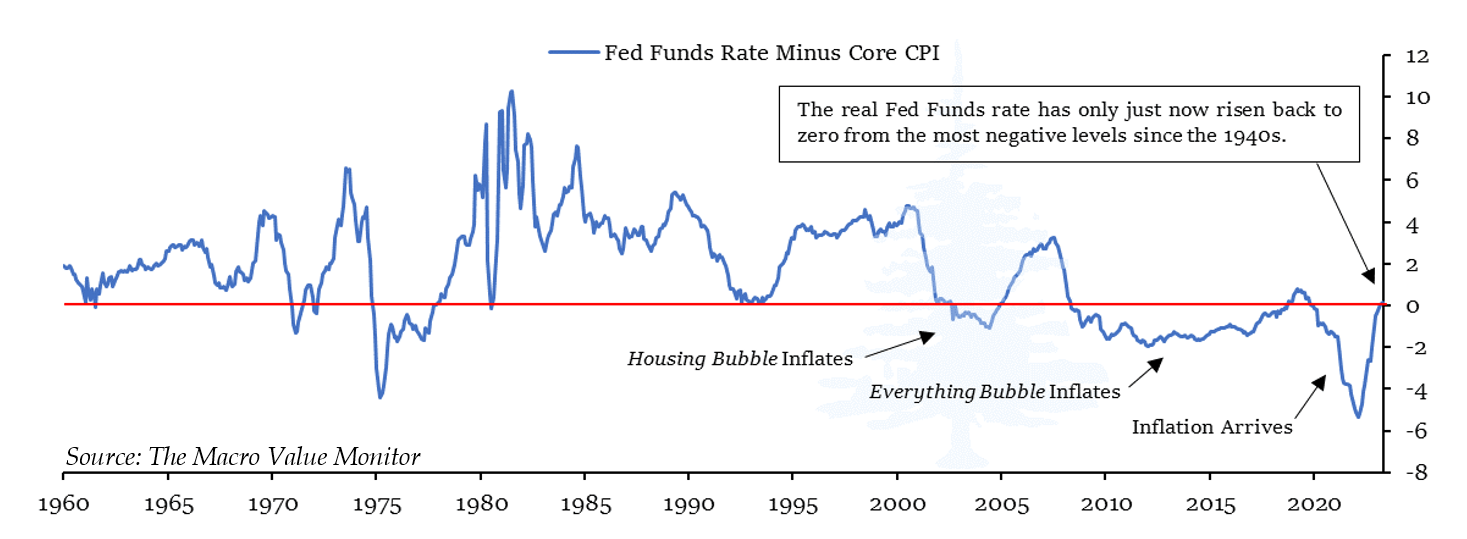

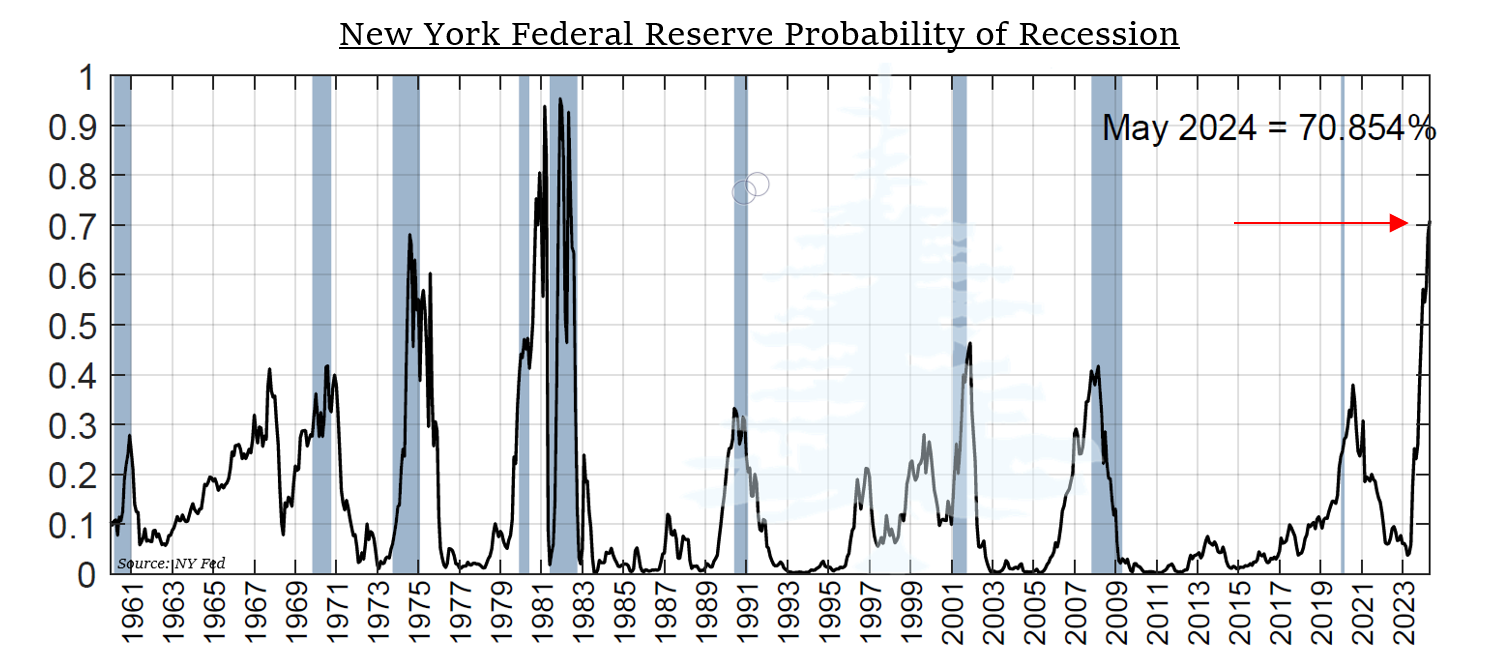

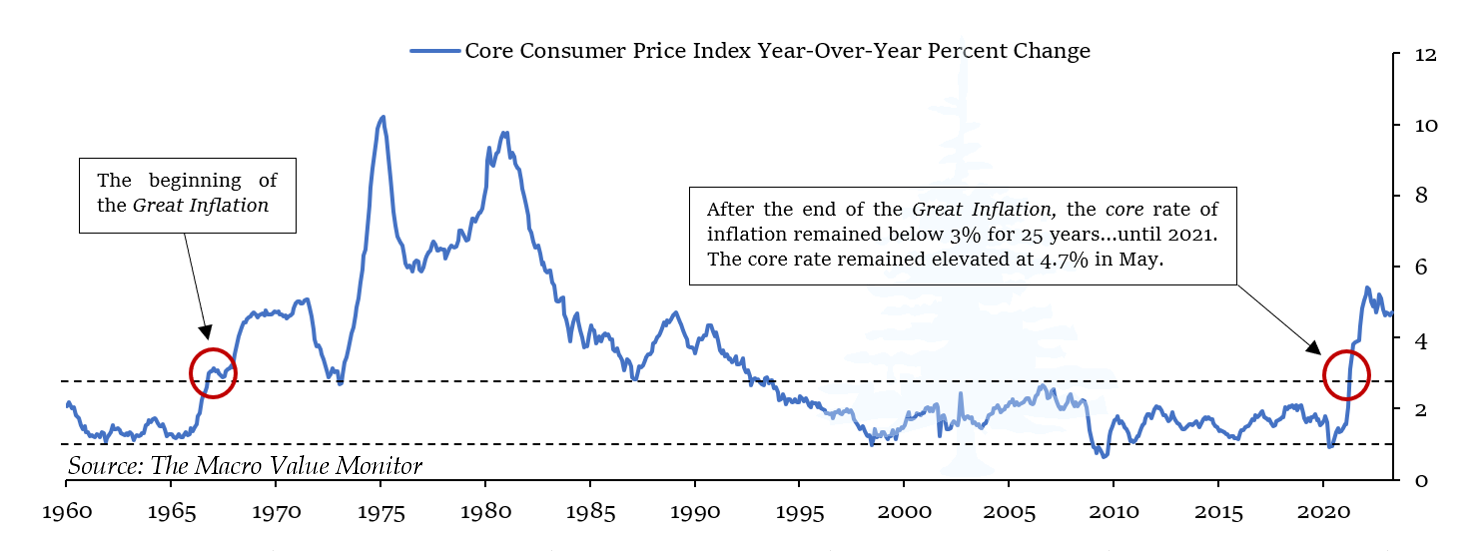

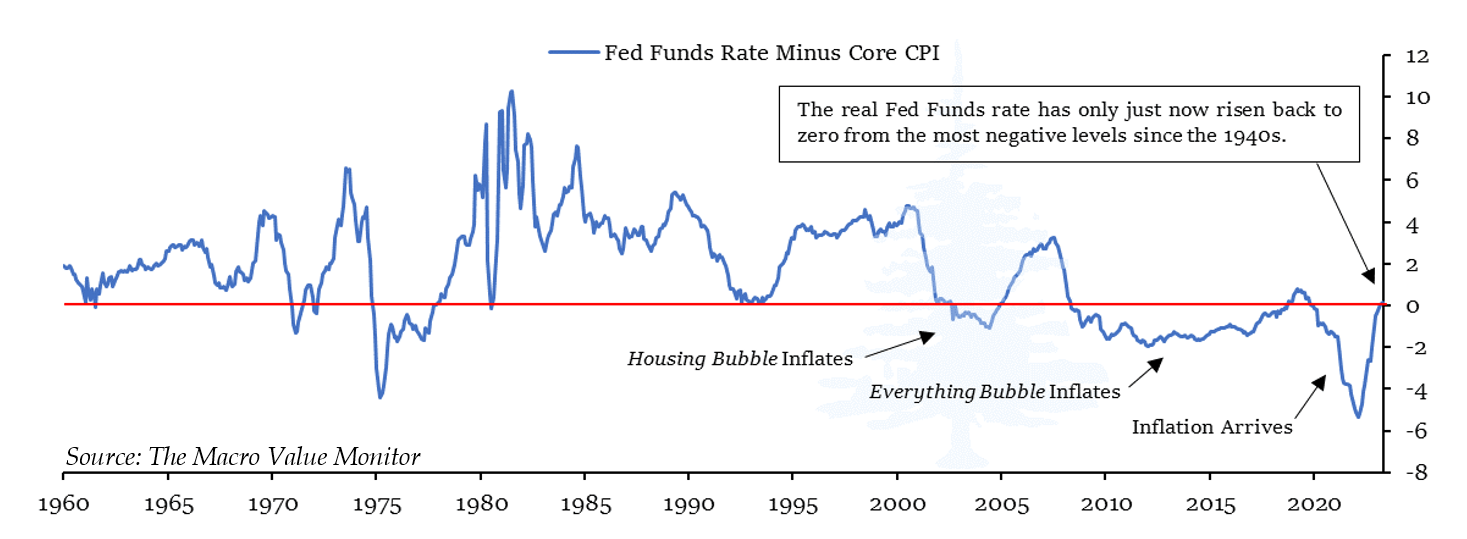

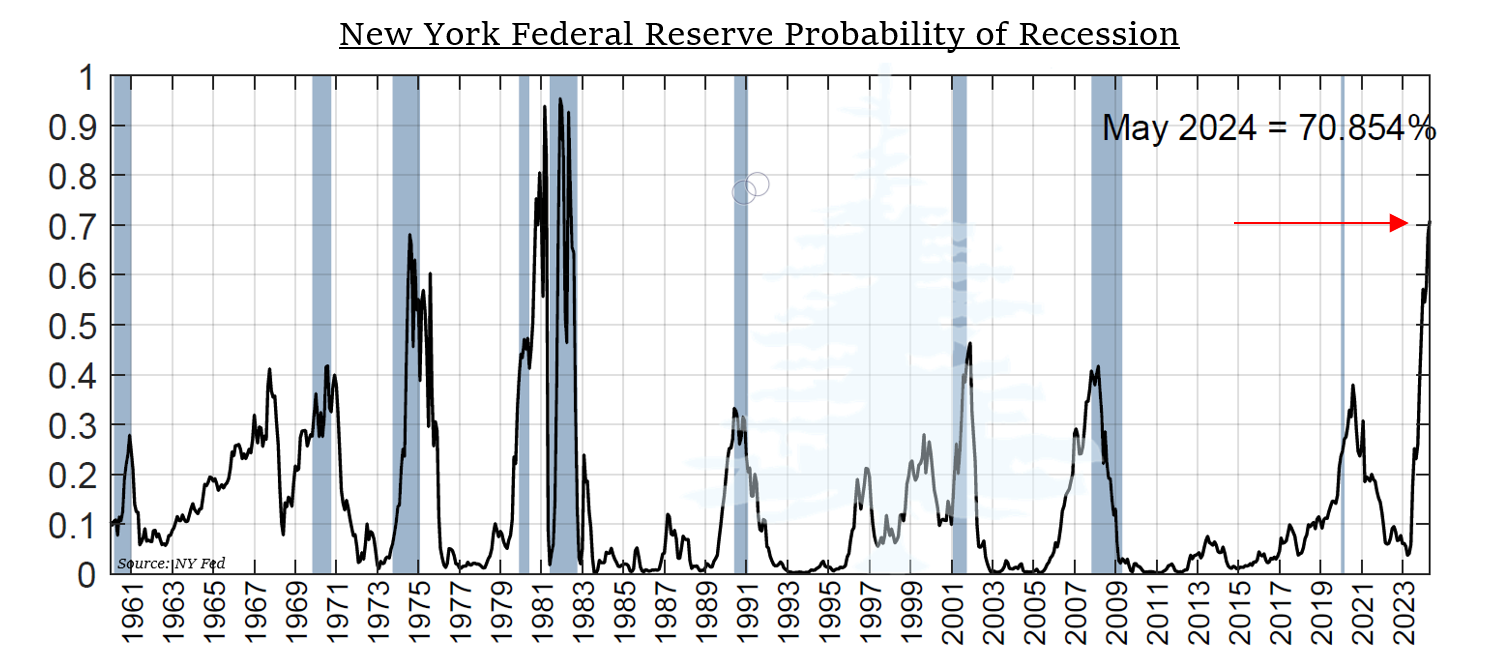

What the statement from the Federal Reserve did not say was that interest rates crossed into positive territory relative to the Core Consumer Price Index over the prior month (chart above), and it is now time to be much more deliberate about raising interest rates. Except for a brief period in 2019, the economy has not been able to sustain growth with positive real, inflation-adjusted interest rates since before the credit crisis, and the Fed is well aware there are already signs that growth will slow further in the year ahead. The staff at the Federal Reserve is still predicting a mild recession later this year, and the New York Fed’s recession model currently estimates there is a greater than 70% chance the economy will be in recession in May 2024. This is the highest odds of recession from their model since the early 1980s (chart below). In these fragile circumstances, the awareness of real, inflation-adjusted interest rates the Federal Reserve learned the hard way through two Great Mistakes comes through in its decisions on monetary policy.

In his press conference after the meeting, Chair Jerome Powell emphasized the Fed’s commitment to tackle today’s elevated inflation just as resolutely as he emphasized the Fed’s commitment to restore the economy to full employment in his June 2021 press conference. When Powell was asked by Courtney Brown of Axios whether the Fed was more confident about returning inflation to a 2% without a recession, he offered this response:

You know, I would just say it this way. I continue to think, and this really hasn’t changed, that there is a path to getting inflation back down to 2 percent without having to see the kind of sharp downturn and large losses of employment that we’ve seen in so many past instances. It’s possible. In a way, a strong labor market is that gradually cools could, it could aid that along. It could aid that along.

But I guess I want to come back to the main thing, which is simply this. We see the committee as you can see from the SEP, the committee is completely unified in the need to get inflation down to 2 percent and will do whatever it takes to get it down to 2 percent over time. That is our plan. And, you know, we understand that allowing inflation to get entrenched into the, in the U.S. economy is the thing that we cannot, cannot allow to happen for the benefit of today’s workers and families and businesses, but also for the future. Getting price stability back and restored will benefit generations of people as long as it’s sustained. And it really is the bedrock of the economy. And you should understand that that is our top priority…

Powell’s response above, and the press conference in its entirety, was an interesting juxtaposition. In 2021, he emphasized the Fed would do everything it could to restore the economy to full employment as soon as possible, and dismissed rising inflation rates as transitory. And now he firmly states that “getting price stability back…is our top priority,” while dismissing the likelihood for a large rise in unemployment due to a recession to achieve that goal. He did not use the now-infamous word transitory to characterize the growing probability of recession over the next year, but he could have.

For those who listened to the press conference from a more strategic viewpoint, the tension between the Federal Reserve’s two statutory mandates – price stability and full employment – was on clear display. It has been more than thirty years since investors have had to navigate a market environment in which monetary policy was being forced to choose whether to stimulate the economy to increase employment at the expense of higher inflation, or whether to withdrawal stimulus to dampen inflation at the expense of employment, but we are in that environment today. When Steve Liesman of CNBC asked Powell what he thought about the relative risks between higher inflation and economic growth, he offered this response:

You know, I would say again that I think that over time, the balance of risks as we move from very, you know, from interest rates that are effectively zero now to five percentage points with an SEP calling for additional hikes. I think we’ve moved much closer to our destination, which is that sufficiently restrictive rate and I think that means by almost by definition that the that the risks of sort of overdoing it and underrate under doing it are getting closer to being in balance. I still think and my colleagues agree that that the risks to inflation are to the upside still. So we don’t we don’t think we’re there with inflation yet because we’re just looking at the data.

You know, if you look at the at the full range of inflation data, particularly the core data, you just you just aren’t seeing a lot of progress over the last year. Headline inflation has come down materially, but as you know, we look at core as a better indicator of where inflation overall is going this officially. So I think, you know what we’d like to see is credible evidence that inflation is topping out and then beginning to come down. That’s what we want to see…

With the most recent reading of the Core Consumer Price index at 4.7%, more than double the Federal Reserve’s official target, Powell is certainly correct in saying that we’re not yet “there with inflation.” The Fed will likely have to keep monetary policy relatively restrictive far longer than investors expect in order to dampen inflation further in the years ahead.

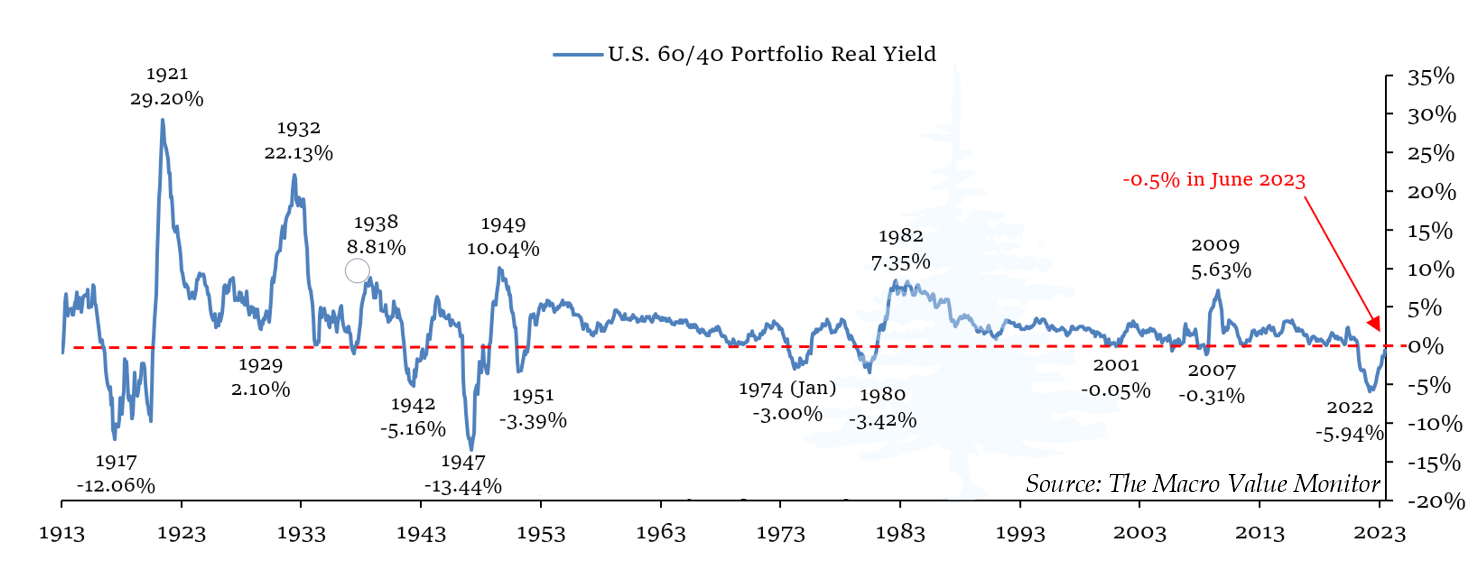

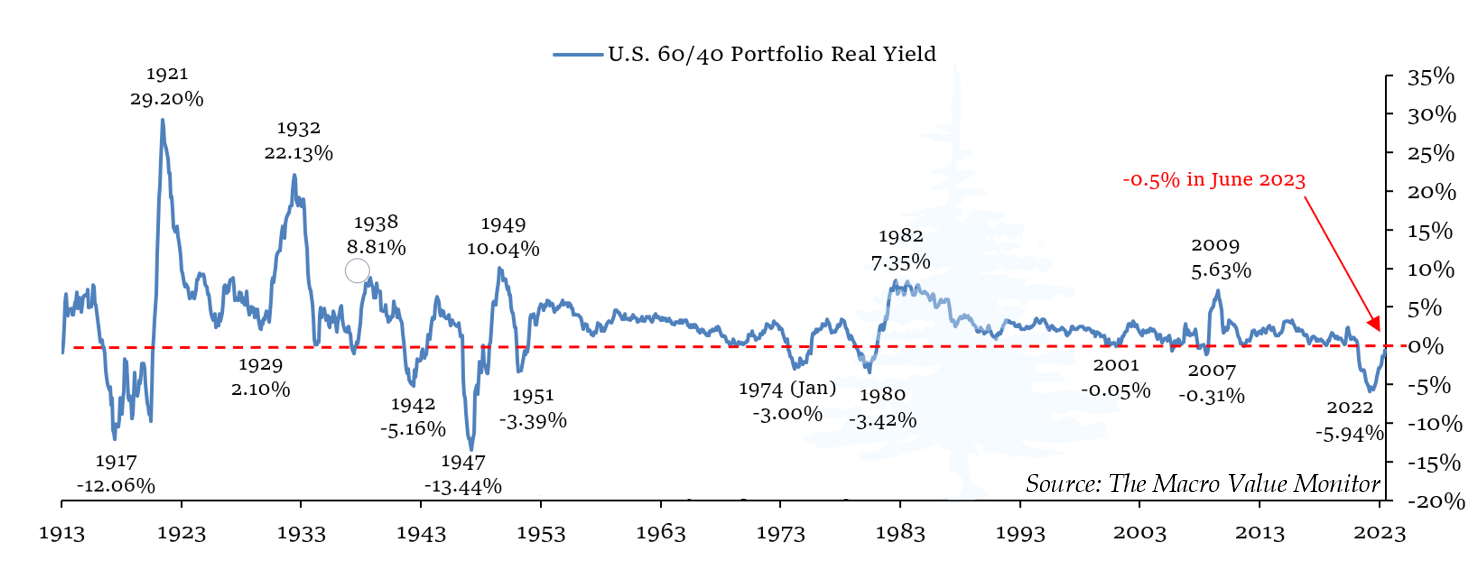

Viewing these circumstances strategically, it is clear financial markets have a number of moves ahead before higher inflation rates and tighter monetary policy are fully priced in. As of this month, the real, inflation-adjusted yield of a standard portfolio of U.S. stocks and bonds remains 0.5% below that of headline inflation (shown below), and 1.2% below the Core CPI.

Negative real portfolio yields are a sign that markets are mispriced, and for investors who navigate financial markets with more strategic chess mindset, instead of a reactionary checkers mindset, maintaining defensive allocations among assets which do well during inflation and recessions will likely be how strategic control will be maintained over the next several years, until stocks and bonds are no longer mispriced. The question is: what does defensive look like in these circumstances?

* * *

The above is Part I of Volume II Issue V of The Macro Value Monitor, a publication focusing on Monetary History, Market Myths, Investing Legends, and Real Global Value.

Part II, The Art of (Paying Less Attention to) Noise, is available on Substack.

The content of this document is provided as general information and is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment or other advice. This material is not to be construed as a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any security, financial product, instrument or to participate in any particular trading strategy. Not all securities, products or services described are available in all countries, and nothing herein constitutes an offer or solicitation of any securities, products or services in any jurisdiction where their offer or sale is not qualified or exempt from registration or otherwise legally permissible.

Although the material herein is based upon information considered reliable and up-to-date, Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC does not assure that this material is accurate, current, or complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. Content in this document may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted, in whole or in part, without prior written consent from Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC — which is usually gladly given, as long as its use includes clear and proper attribution. Contact us for more information.

© Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC

Checkers vs Chess Amid an Inflationary Great Mistake

June 30, 2023

Roughly a year into their campaign against high inflation, policy makers are some way from being able to declare victory. In the U.S. and Europe, underlying inflation is still around 5% or higher even as last year’s heady increases in energy and food prices fade from view. On both sides of the Atlantic, wage growth has stabilized at high levels and shows few signs of steady declines…

All that puts major central banks in a tricky spot. They need to decide if inflation has stalled way above their 2% target, which could require much higher interest rates to fix, or if inflation’s decline is only delayed. Get the call wrong, and they could push the rich world into a deep recession or force it to endure years of high inflation.

“It’s not an enviable situation that central banks are in,” said Stefan Gerlach, a former deputy governor of Ireland’s central bank. “You could make a major mistake either way.”

~ The Wall Street Journal, June 19, 2023

Chess is like looking across an ocean. Checkers is like looking down a well.

~ Dr. Marion F. Tinsley

Inflation Strategy Amid Monetary Stimulants Gone Awry

One year ago, we visited the pages of a diary from 1931, a diary which contained the thoughts of a young lawyer in Youngstown, Ohio, who was living through the early days of the Great Depression. Benjamin Roth began to write down his thoughts and record the events around him when he realized he was living through a period of economic turmoil that was different from anything else he had experienced up to that time.

After World War I, Roth had witnessed the post-war boom when he arrived back home from Europe. At the time, soaring retail sales and real estate prices accompanied the return of soldiers and the end of the wartime economy, as exuberant consumers, flush with cash, shed the austere mentality of the war years and spent lavishly. As we chronicled in these pages last April, this postwar boom ended in a brief depression when the Federal Reserve decided to tackle inflation by shrinking its balance sheet in 1921, a downturn which bankrupted future president Harry Truman’s haberdashery, Truman & Jacobson.

In the years that followed the early 1920s depression, however, the economy had boomed again. Roth began his diary by noting how extraordinary the 1920s economy was. With Europe in ruins, America became the main supplier for raw materials and consumer goods to Western Europe, as well as American consumers. Mass-produced manufactured goods such as radios and automobiles were newly affordable to the masses, and production and employment soared. The stock market boomed as well, and for the first time, the broader public became enchanted with Wall Street. Companies began issuing “common shares” for the first time in the early 1920s. Although they did not have a guaranteed dividend like their preferred relatives, common shares were issued in smaller denominations, and that opened the floodgates to millions of investors and speculators.

Yet, as Roth reflected in 1931, the economy had also began to show cracks as early as the mid-1920s. As Wall Street boomed, it financed the first expansion of large retail chain stores into small town America, and this bankrupted thousands of small businesses in Ohio alone.

As an attorney who processed many of the bankruptcy filings, Roth witnessed this erosion of locally owned business firsthand. As a greater share of retail profits began flowing to Chicago and New York, instead of remaining in the local economy, commercial real estate in Youngstown began to falter. This was soon accompanied by a decline in farmland values, as a recovery in European farm production reduced exports and weighed down crop prices. In Youngstown, a decline in steel prices in the latter half of the 1920s hit the increasingly strained local economy particularly hard.

By 1931, it had been two years since the speculative peak of the stock market in 1929, but the steady erosion of Youngstown’s local economy dated back years before the peak in New York – and it had begun to cripple local banks. The first bank closure was announced on August 5th, 1931, when Home Savings & Loan closed its doors. For the stunned citizens of Youngstown, this marked the moment when the downturn with roots in the mid-1920s began rising above the surface in ways that put their supposedly-safe cash savings at risk.

What Benjamin Roth did not know at the time, and could not have known, was that in the summer of 1931 the Federal Reserve was already in the middle of its First Great Mistake. By the time Home Savings & Loan in Youngstown failed, real, inflation-adjusted interest rates had soared, but few understood the destructive impact surging real interest rates were imparting. On the surface, it seemed as if rates were lower. Interest rates had fluctuated between 4% and 5% throughout 1929, and after the stock market crashed, they steadily declined. By the time Benjamin Roth began his diary in June 1931, interest rates had fallen to just 0.55%. These were the lowest interest rates in memory.

With interest rates near zero, many Federal Reserve governors assumed monetary policy was “loose,” but unfortunately, that was not the case. When adjusted for inflation, interest rates fluctuated between 3% and 5% throughout most of 1929, but after the stock market crashed in October 1929, prices throughout the economy began to fall: in the year after the crash, the consumer price index had declined 4%. Although nominal interest rates had declined from 4% to 1.75% during that time, real interest rates, adjusted for the 4% decline in prices, had risen to 5.75% in 1930. By 1931, the decline of prices throughout the economy accelerated to a 10% annual rate, and this translated the 0.55% nominal interest rate to a 10.55% real, deflation-adjusted interest rate.

Instead of monetary policy being “loose,” by 1931 real interest rates had risen to the highest levels in more than a decade. This surge ignited an asset liquidation and credit contraction that marked the end of the cyclical downturn from the peak in 1929, and the beginning of the Great Depression.

The Great Mistake made by the Federal Reserve in the 1930s was its failure to understand the importance of real interest rates, while also not appreciating the long-term risks that come with a large-scale, economy-wide credit contraction.

At the time, the consensus among Federal Reserve governors was that monetary policy was loose enough, with interest rates near zero. Other governors thought the economy needed a proper downturn in order to purge the excesses of the boom years, and when the downturn continued despite low interest rates, it reinforced this tough love view. As Fed governor Charles Hamlin put it in November 1929, just after the crash in the stock market the month before: “These events are deplorable, but they were of course inevitable and could not have been avoided.” Attitudes such as these led to a complacent intake of the mounting troubles in banks throughout the country after 1929, and they resulted in a hands-off approach as the economic contraction accelerated dramatically in 1931.

Yet this hands-off approach ultimately led to severe consequences for the Federal Reserve: it resulted in partial takeovers of monetary policy by the U.S. Treasury department in 1933 and 1937, and ultimately to a full takeover in 1942. The loss of independence as a result of the complacency in the early years of the Great Depression left deep scars in the halls of the Eccles building, and as a result, the Fed has aggressively intervened at every sign of incipient deflation since then.

Nine decades later, those powerful institutional memories forged by the First Great Mistake were on full display as the Federal Reserve responded to the impact of the Covid pandemic.

Two years ago, on June 16, 2021, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell took questions from reporters at his regular press conference following the meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee. At the time, the Fed had decided to keep the Fed Funds rate at zero, and had also decided to keep expanding its balance sheet by $120 billion a month. Unlike the Federal Reserve of 1931, the Federal Reserve of 2021 was convinced it could not do enough to hasten the return of a full employment economy in the wake of the pandemic, and after a decade-long recovery after the financial crisis.

When Chair Powell was asked by Rachel Seigel of The Washington Post about the Fed’s outlook for the jobs market two years hence, in 2023, given the Fed’s then-current policies, he had this to say:

So I would say, if you look at the labor market and you look at the demand for workers and the level of job creation and think ahead, I think it’s clear, and I am confident, that we are on a path to a very strong labor market—a labor market that, that shows low unemployment, high participation, rising wages for people across the spectrum. I mean, I think that’s shown in our projections, it’s shown in outside projections. And if you look through the current time frame and think one and two years out, we’re going to be looking at a very, very strong labor market…

The next reporter, Paul Kiernan of The Wall Street Journal, asked Powell how he felt about the recent rise of inflation. He pointed out that the annualized inflation rate over the prior three months had risen to 8.4%, the highest in four decades, and he asked Powell “how much longer we can sustain those, those kinds of rates before you get nervous?” Powell offered this response:

So inflation has come in above expectations over the last few months. But if you look behind the headline numbers, you’ll see that the incoming data are, are consistent with the view that prices—that prices that are driving that higher inflation are from categories that are being directly affected by the recovery from the pandemic and the reopening of the economy…

When will we be seeing [those trends reverse]? We’re not sure. That narrative seems, still seems quite likely to prove correct, although, you know, as I pointed out at the last press conference, the timing of that is, is pretty uncertain, and so are the, the effects in the near term. But over time, it seems likely that these very specific things that are driving up inflation will be—will be temporary…

So I can’t give you an exact number or an exact time, but I would say that we do expect inflation to move down. If you look at the—if you look at the forecast for 2021 and—sorry, 2022 and 2023 among my colleagues on the, on the Federal Open Market Committee, you will see that people do expect inflation to move down meaningfully toward our goal [of 2%]. And I think the full range of inflation projections for 2023 falls between 2 and 2.3 percent, which is consistent with our—with our goals.

The final exchange in the press conference came from Bloomberg’s Michael McKee. In his question, he attempted to ask Chair Powell how he was reconciling the apparent inconsistency between the discounting of the actual inflation data that was coming in, assuming it would simply resolve itself in time, while also stating the Fed would rely less on forecasts (and assumptions) and be more data-dependent in its decision making. These were the new goals the Fed outlined in its Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy the prior year.

MICHAEL MCKEE. Mr. Chairman, of course you’ll be shocked to learn that you have some critics on Wall Street. And I would like to paraphrase a couple of their criticisms and get your reaction to them. One is that the new policy framework is that you react to actual data and do not react to forecasts, yet the actual inflation data is coming in hot and you’re relying on the forecast that it will cool down in order to make policy. I wanted to get your view on how you square that. Another is that you have a long runway, you’ve said, for tapering with announcements. But if the data keep coming in faster than expected, are you trapped by fear of a taper tantrum from advancing the time period in which you announce a taper? And, finally, you’ve said the Fed knows how to combat inflation, but raising rates also slows the economy. And there’s a concern that you might be sacrificing the economy if you wait too long and have to raise rates too quickly.

CHAIR POWELL. So that’s a—that’s a few questions there. So let me say, first, I think people misinterpret the framework. I think the—there’s nothing wrong with the framework, and there’s nothing in the framework that would in any way, you know, interfere with our ability to pursue our, our goals. That’s for starters…

You know, your specific question, I guess, was, will we be behind the curve? And, you know, that’s, that’s not the situation we’re facing at all. The situation that we, we addressed in our—in our Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy was a situation in which employment was at very high levels, but inflation was low. And what we said was, we wouldn’t raise interest rates just because unemployment was low and employment was high if there was no evidence of inflation or other troubling imbalances. So that’s what we said.

That is not at all the current situation. In the current situation, we have many millions of people who are unemployed, and we have inflation running well above our target. The question we face with this inflation has nothing to do with our framework. It’s a very different, very difficult version of a standard investment—sorry, a central banking question. And that is, how do you separate in inflation—how do you separate things that, that follow from broad upward price pressures from things that really are a function of, of sort of idiosyncratic factors…

MICHAEL MCKEE. If you raise rates to control inflation, you also slow the economy. And the history of the Fed is that sometimes you go too far.

CHAIR POWELL. That’s right. And we—look, we have to balance the two—the two goals: maximum employment and price stability. Often they are—they do pull in the same direction, of course. But when we—when we raise interest rates to control inflation, there’s no question that has an effect on activity. And that’s the channel—one of the channels through which we get to inflation. We don’t think that we’re in a situation like that right now. We think that the economy is recovering from a deep hole—an unusual hole, actually, because it’s to do with, with shutting down the economy. It turns out it’s a heck of a lot easier to create demand than it is to, you know, to bring supply back up to snuff. That’s happening all over the world. There’s no reason to think that that process will last indefinitely. But we’re going, you know, we’re going to watch carefully to make sure that, that evolving inflation and our understanding of what’s happening is, is, is right. And in the meantime, we’ll conduct policy appropriately.

In these passages from Powell’s press conference two years ago, the complacency in the face of rising inflation bears an eerie resemblance to the complacency the Federal Reserve showed toward rising unemployment and bank failures after 1929.

In 1930 and 1931, the Federal Reserve operated on the assumption that the excesses of the late 1920s boom needed to be corrected, and once they were corrected, growth would resume just as it had prior to 1929, without any additional support from monetary policy. Soaring real interest rates, falling commodity prices, and the impact declining real estate values was having on bank balance sheets and broad measures of money supply, were either rationalized as necessary to correct the excesses of the late 1920s, or ignored. The depression that followed was the deepest downturn of the 20th century.

Ninety years later, in 2021, similar assumptions were made about inflation returning to its prior trajectory, without the need for any additional restraint from monetary policy, when, in fact, just as in 1931, the old regime was becoming history amid the complacency.

Monetary policy infamously operates with long and variable lags, and successively navigating the impact monetary stimulus or withdrawal has on prices throughout the economy and financial markets requires a strategic mindset that is thinking and planning many moves ahead.

Checkers and chess are both played on boards with sixty-four squares, but there the similarity ends. In the game of checkers, each piece is interchangeable, and able to move in the same way – forward. In checkers, players generally attempt to take as many of their opponent’s pieces as possible, as quickly as they can, while losing fewer of their own, using moves which are fairly linear: moving one square at a time, one jump takes one piece, two successive jumps take two pieces, etc. When a piece is “kinged,” its range of motion increases, but it continues to move in the same linear way. It is a game that largely rewards black and white, reactionary problem solving.

Chess, on the other hand, is a game which is played with different goals, and is won with a much more complex, strategic approach. With six different kinds of pieces, all of which move in different ways, and the capture of only one of which ends the game, chess is more about controlling the board than capturing or losing pieces. An almost infinite number of progressions can achieve this. As long as one’s king remains protected, other pieces can be sacrificed to establish that control, and winning is less about numerical advantage than strategic dominance. The player who dominates the board, and corners their opponent’s king in the fewest moves while protecting their own, wins the game.

In chess, if you are merely reacting to the moves your opponent makes as they make them, you are already falling into their trap and on your way to losing the game. In the financial markets, the same can be said of investors who are reacting to current data, especially current inflation data.

Major central banks around the world have been scrambling to address rising inflation rates since last year, but the combined balance sheet of the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, the Bank of Japan, and the People’s Bank of China highlights what they are struggling against – themselves. With a combined balance sheet 5.6 times the size it was in 2007, the global supply of money on which all credit in the largest economies is based many times larger than what it was before the financial crisis. And as we have seen in the bond market and banking turmoil in the U.K., Europe, and here in the U.S. over the past year, shrinking that base money supply is no painless task.

Price inflation is the end result of a long and variable chain of circumstances, and the root of that progression is the base money supply. Those who listened to Jerome Powell’s press conference in June 2021 with a checkers mentality, thinking linearly, and reacting to what was in the rear-view mirror, found themselves badly burned in 2022, when inflation proved far more widespread and resilient than the Fed expected. Those who listened to that same press conference with a chess mentality could visualize what the market risks were in that moment, and what the consequences could be if some of those risks surfaced. The difference in thinking in black-and-white terms, versus thinking in a more strategic manner, proved to be the difference between being trapped by the market reset in 2022, and taking advantage of it.

This past month, the Federal Reserve decided to pause its rate-hiking campaign for the first time since it belatedly began to address rising inflation a year ago. It left the Fed Funds rate target range at 5-5.25% and issued a statement that said holding interest rates at this level will allow the Fed “to assess additional information and its implications for monetary policy.”

What the statement from the Federal Reserve did not say was that interest rates crossed into positive territory relative to the Core Consumer Price Index over the prior month (chart above), and it is now time to be much more deliberate about raising interest rates. Except for a brief period in 2019, the economy has not been able to sustain growth with positive real, inflation-adjusted interest rates since before the credit crisis, and the Fed is well aware there are already signs that growth will slow further in the year ahead. The staff at the Federal Reserve is still predicting a mild recession later this year, and the New York Fed’s recession model currently estimates there is a greater than 70% chance the economy will be in recession in May 2024. This is the highest odds of recession from their model since the early 1980s (chart below). In these fragile circumstances, the awareness of real, inflation-adjusted interest rates the Federal Reserve learned the hard way through two Great Mistakes comes through in its decisions on monetary policy.

In his press conference after the meeting, Chair Jerome Powell emphasized the Fed’s commitment to tackle today’s elevated inflation just as resolutely as he emphasized the Fed’s commitment to restore the economy to full employment in his June 2021 press conference. When Powell was asked by Courtney Brown of Axios whether the Fed was more confident about returning inflation to a 2% without a recession, he offered this response:

You know, I would just say it this way. I continue to think, and this really hasn’t changed, that there is a path to getting inflation back down to 2 percent without having to see the kind of sharp downturn and large losses of employment that we’ve seen in so many past instances. It’s possible. In a way, a strong labor market is that gradually cools could, it could aid that along. It could aid that along.

But I guess I want to come back to the main thing, which is simply this. We see the committee as you can see from the SEP, the committee is completely unified in the need to get inflation down to 2 percent and will do whatever it takes to get it down to 2 percent over time. That is our plan. And, you know, we understand that allowing inflation to get entrenched into the, in the U.S. economy is the thing that we cannot, cannot allow to happen for the benefit of today’s workers and families and businesses, but also for the future. Getting price stability back and restored will benefit generations of people as long as it’s sustained. And it really is the bedrock of the economy. And you should understand that that is our top priority…

Powell’s response above, and the press conference in its entirety, was an interesting juxtaposition. In 2021, he emphasized the Fed would do everything it could to restore the economy to full employment as soon as possible, and dismissed rising inflation rates as transitory. And now he firmly states that “getting price stability back…is our top priority,” while dismissing the likelihood for a large rise in unemployment due to a recession to achieve that goal. He did not use the now-infamous word transitory to characterize the growing probability of recession over the next year, but he could have.

For those who listened to the press conference from a more strategic viewpoint, the tension between the Federal Reserve’s two statutory mandates – price stability and full employment – was on clear display. It has been more than thirty years since investors have had to navigate a market environment in which monetary policy was being forced to choose whether to stimulate the economy to increase employment at the expense of higher inflation, or whether to withdrawal stimulus to dampen inflation at the expense of employment, but we are in that environment today. When Steve Liesman of CNBC asked Powell what he thought about the relative risks between higher inflation and economic growth, he offered this response:

You know, I would say again that I think that over time, the balance of risks as we move from very, you know, from interest rates that are effectively zero now to five percentage points with an SEP calling for additional hikes. I think we’ve moved much closer to our destination, which is that sufficiently restrictive rate and I think that means by almost by definition that the that the risks of sort of overdoing it and underrate under doing it are getting closer to being in balance. I still think and my colleagues agree that that the risks to inflation are to the upside still. So we don’t we don’t think we’re there with inflation yet because we’re just looking at the data.

You know, if you look at the at the full range of inflation data, particularly the core data, you just you just aren’t seeing a lot of progress over the last year. Headline inflation has come down materially, but as you know, we look at core as a better indicator of where inflation overall is going this officially. So I think, you know what we’d like to see is credible evidence that inflation is topping out and then beginning to come down. That’s what we want to see…

With the most recent reading of the Core Consumer Price index at 4.7%, more than double the Federal Reserve’s official target, Powell is certainly correct in saying that we’re not yet “there with inflation.” The Fed will likely have to keep monetary policy relatively restrictive far longer than investors expect in order to dampen inflation further in the years ahead.

Viewing these circumstances strategically, it is clear financial markets have a number of moves ahead before higher inflation rates and tighter monetary policy are fully priced in. As of this month, the real, inflation-adjusted yield of a standard portfolio of U.S. stocks and bonds remains 0.5% below that of headline inflation (shown below), and 1.2% below the Core CPI.

Negative real portfolio yields are a sign that markets are mispriced, and for investors who navigate financial markets with more strategic chess mindset, instead of a reactionary checkers mindset, maintaining defensive allocations among assets which do well during inflation and recessions will likely be how strategic control will be maintained over the next several years, until stocks and bonds are no longer mispriced. The question is: what does defensive look like in these circumstances?

* * *

The above is Part I of Volume II Issue V of The Macro Value Monitor, a publication focusing on Monetary History, Market Myths, Investing Legends, and Real Global Value.

Part II, The Art of (Paying Less Attention to) Noise, is available on Substack.

The content of this document is provided as general information and is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment or other advice. This material is not to be construed as a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any security, financial product, instrument or to participate in any particular trading strategy. Not all securities, products or services described are available in all countries, and nothing herein constitutes an offer or solicitation of any securities, products or services in any jurisdiction where their offer or sale is not qualified or exempt from registration or otherwise legally permissible.

Although the material herein is based upon information considered reliable and up-to-date, Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC does not assure that this material is accurate, current, or complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. Content in this document may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted, in whole or in part, without prior written consent from Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC — which is usually gladly given, as long as its use includes clear and proper attribution. Contact us for more information.

© Sitka Pacific Publishing, LLC

Investment Management

Before investing, we will discuss your goals and risk tolerances with you to see if a separately managed account at Sitka Pacific would be a good fit. To contact us for a free consultation, visit Getting Started.

Macro Value Monitor

To read a selection of recent client letters and be alerted when new letters are posted to our public site, visit Recent Client Letters.